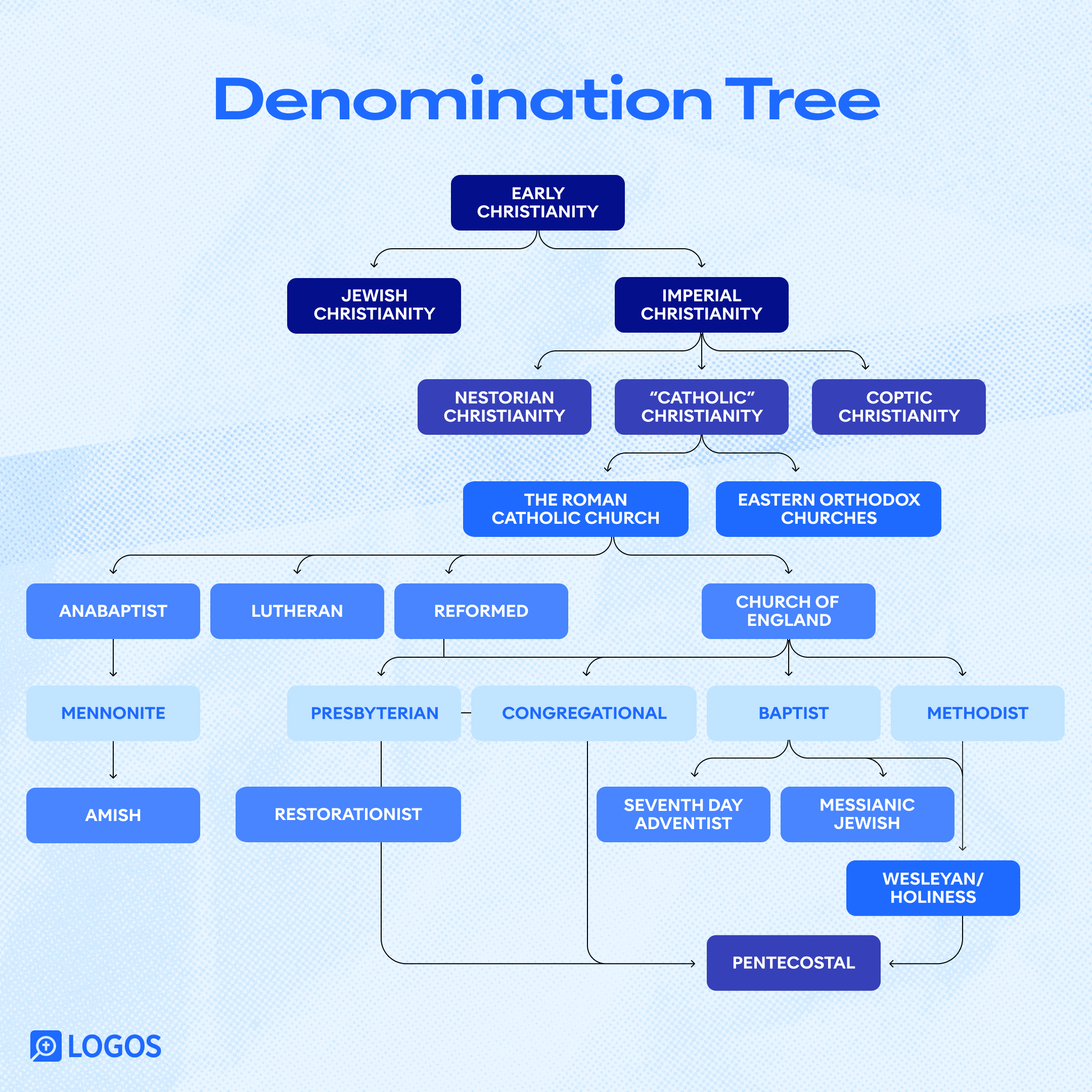

It’s common for Christians today to think of their church bodies as denominations; that is, different varieties of a common religion. This tendency is so pervasive that churches who want to shed conventional labels will even call themselves “non-denominational.” People ask how many denominations there are, and critics will assert that the “thousands” of denominations are proof that Christians cannot agree about what is true.

But what is a denomination in the first place?

The term “denomination” originally simply meant the act of naming things or categorizing them according to common group labels (notice the nomina, Latin for “name”). It only began to be applied to churches in the eighteenth century.1 For Roman Catholicism, there is only “the Church” and then “separated brethren.”2 Reformation church confessions also tend to speak of only one church. Some of them contrast “the true Church” with “sects who call themselves the Church.”3 Others say that the church can be “more or less visible.”4 The Church of England speaks of “particular or national church[es].”5 This is important to note because when people use the term “denomination,” they often assume a specific sort of church and theology—usually an American and an evangelical one. But not all denominations agree on what a denomination is or even recognize the validity of the concept.

Still, the language of denominations is probably here to stay. The term means different things to different people, but we’ll just use it here to mean a particular church group which recognizes itself and distinguishes itself from others. Denominations can also be classified in different ways. They can be defined by their history and point of origin. They can be defined by their set of beliefs. They can even be defined by the ethnicity of their membership. Depending on how you organize them, multiple groups can be members of the same denomination, or they can each be considered to be their own denomination.

Disclaimer

This is a complex topic. Though we strive for accuracy, oversimplification is inevitable. Additionally, in the interest of tracing the distinctions between denominations, comparative work can appear to exaggerate those distinctions. Finally, what is unique about a position—i.e., what distinguishes it from others—is not always the same as what is essential to that position; so an effect of comparative work is people may feel their denomination is not represented correctly or fairly. This is not intentional, nor does it necessarily betray a bias/prejudice of the author’s: it is a side-effect of this sort of comparative evaluation.

We stand by what we publish, but if you still have an objection, remember: all Christian denominations believe in grace. We ask for grace for our writer and editors, without which it is not possible to have conversations like this.

Table of contents

- Early Christian developments

- The Protestant Reformation

- Modern denominations

- 20th- and 21st-century evangelicalism

2 or 3 big denominations?

You will very often hear people speak of two major divisions between Christian denominations: Catholic and Protestant. Other times the divisions are between Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Protestant churches. This way of explaining things breaks down very quickly, though, because the churches being called “Protestant” are too diverse to be classified together. This approach also skips over the Anabaptist tradition entirely. A better approach will highlight around fifteen major denominations, though you could number them differently if you chose to get more (or less) specific.

The question of how many denominations there are also requires some understanding of the difference of a broadly orthodox Christian body and a group that is far enough outside of the bounds of orthodoxy that they are typically not recognized as Christian. This is a highly debated point, but the most basic dividing line is usually drawn at the doctrines of the Trinity and the deity of Christ. If a group does not affirm these, then they are not usually considered to be a Christian group, even if they originally developed out of Christian churches. Examples of important groups which are not considered orthodox Christian churches would be the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Mormons), the Jehovah’s Witnesses (Watchtower Society), and the Quakers (or Society of Friends).

Early Christian developments

Both Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy derive from the ecumenical church of the Roman Empire. Christianity emerged in Palestine from among a religious and ethnic community that we now refer to as Judaism. Inheriting the earlier tradition of the religion of Abraham, David, and the Hebrew prophets, Christians claimed that Jesus of Nazareth was the promised Messiah and indeed the eternal Son of God. By the end of the first century, Christianity had spread across the Mediterranean, throughout North Africa, and into Western Europe. All of these areas were a part of the Roman Empire, which would itself become thoroughly Christianized over the next two hundred years.

But early Christianity also spread into regions beyond the borders of the empire. Christian churches were formed in India by the first century.6 They also appeared in Persia at either the end of the first century or during the second.7 From Persia, Christian churches moved east into China by at least the seventh century.8 In addition to this, there remained an identifiably “Jewish” Christian group until the fifth century.9 Each of these groups could be considered distinctive denominations of ancient Christianity.

Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy are held together by their common relationship to the Roman Empire, their mutual recognition of the organization and governmental structure according to major metropolitan archbishops called “patriarchs,” and their acceptance of the first seven ecumenical councils. Initially, there were four major patriarchs: Jerusalem, Antioch, Rome, and Alexandria. The fifth, Constantinople, was added after Constantine moved the capital of the empire to that city. Those churches which had a direct relationship with these archbishops recognized themselves as “the catholic church” for the first thousand years of Christian history. They shared a belief in the Trinity—that there is only One God, but One who exists in Three Persons—as well as the two natures of Christ in one person. They also believed that the church should be governed by bishops with priests and deacons ministering in the congregations. These churches had many features of the worship services in common, practicing what we would now refer to as formal or “liturgical” worship. They also had a common appreciation for ascetic piety, with monks, nuns, and other holy men holding a particular place of honor.10

Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy began to take on their particular characteristics as unique “denominations” through the disagreements that gradually began to surface. Heightening in the 800s, these would come to a breaking point in the schism of 1054. Originally, the differences between these two groups had simply been language and culture. The Eastern churches spoke Greek and more closely aligned with the Roman Empire, what we now usually call Byzantium. The churches that we consider “Roman Catholic” were in the West, spoke Latin, and quickly began to mix with the new Barbarian converts. Since the Western Roman Empire collapsed in the fourth and fifth centuries, the Bishop of Rome became a singular leader over both the churches and the new kingdoms.11

A division in the broader church began to arise mostly over the question of leadership. Who was in charge? Was it the collection of patriarchs working together in conference, or was it the Bishop of Rome? Along with this political dispute, matters which had been understood as minor became battlegrounds. Two of the most significant were whether the sacrament of Holy Communion required leavened or unleavened bread and whether the filioque clause, which says that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son,12 should be added to the Nicene Creed.13 In 1054, the Bishop of Rome (the Pope) and the Patriarch of Constantinople excommunicated one another. The Christian East and the Christian West began to definitively part ways.

Eastern Orthodoxy

Eastern Orthodoxy refers to those churches which continued from the earlier arrangement of patriarchates, spoke Greek, and shared a common worship and church calendar. These churches sent missionaries into the Slavic countries and eventually into Russian lands. They teach that churches must be governed by bishops, whom they believe descend by ordination from the original apostles. These bishops rule together in synods or councils, and the leading bishop over each national church is called a patriarch.

As important as bishops are to Eastern Orthodox churches, the monks have held an equally important position. In the eleventh century, Symeon the New Theologian went so far as to write:

Prior to this, as successors to the holy Apostles, only bishops received the power to bind and loose. But as the time passed, the bishops became corrupt, and this fearful undertaking passed on to priests who had a blameless life and were worthy of grace. And later, the priests as well, as the bishops associated with and became just like the rest of the people. … Then the power to bind and loose was transferred to the chosen among the people of God, that is to say, to the monks.14

Orthodox Christians believe that the central focus of salvation is theosis, or union with God, and they believe that this is a continual process which begins at baptism, wherein a person is regenerated. It continues through a life of prayer, ascetic discipline, and the sacramental life of the church. Eastern Orthodox churches promote a thorough seasonal practice of fasting and ascetic discipline.

Orthodox Christians believe in a real presence of Christ in the Lord’s Supper. They do not affirm a specific doctrinal formulation in the same way that Roman Catholics do, but they do insist on a literal understanding of Christ’s body and blood being present in the bread and wine of the sacrament.

Orthodox Christians also venerate icons, through which they believe they pray to and honor the departed saints. This is a central part of their corporate worship, and it is also a feature of their personal and private devotional practice. The most important figure in their cult of the saints is Mary, the mother of Jesus, whom they call Theotokos, or the Godbearer.

Orthodox Christians affirm the books of the Old and New Testament as canonical Scripture, with the possible exception of the book of Revelation. They also recognize other books, both from before and after the writing of the New Testament, to be Scripture. Most Orthodox recognize a distinction between “canonical” books which hold a primary position and “deuterocanonical” books which are read in the services but understood to be of a somewhat lesser authority. There has been regional variation within Orthodoxy as to which books are considered canonical, and many scholars argue that Orthodoxy does not have a formally closed canon.15 Orthodox Christians also believe in the authority of sacred tradition and of the early ecumenical councils.

While having much in common with Roman Catholicism, Eastern Orthodox Christians do not insist on identifying the number of sacraments to be seven, do not require priestly celibacy, and have less institutional unity. Historically, Orthodox churches organized themselves nationally and translated their worship into the language of the nation. Each national church claimed its own right to ordain clergy and administer discipline. With widespread immigration to Western nations, many of these older jurisdictional boundaries now overlap, and it is not unusual to have several different kinds of Orthodox churches in the same city.

Learn more about the Orthodox faith:

What Is the Orthodox Faith? 9 Facts about the Orthodox Church

Pascha: How Eastern Orthodox Christians Celebrate the Resurrection

Orthodox libraries:

Roman Catholicism

Roman Catholicism refers to the parishes and clergy which organize themselves under the Bishop of Rome. They typically refer to themselves simply as “Catholics.” Like Orthodoxy, Roman Catholicism teaches the succession of bishops from the apostles, but it has a specific understanding of this doctrine. It understands itself as a global institution, with a singular head bishop, the bishop of Rome or the Pope, who possesses immediate jurisdiction over every other church.16 The Pope can, according to the doctrine of Roman Catholicism, speak infallibly when he makes official declarations ex cathedra.

Roman Catholicism organizes its theology around seven sacraments. The Christian life is understood to begin at baptism, wherein original sin is forgiven. Confirmation is understood to be the imparting of the Holy Spirit at a time after baptism, usually after a period of catechesis. Sins committed after baptism are forgiven through the sacrament of penance, which is usually now called “reconciliation.” Reconciliation requires personal contrition, acts of satisfaction prescribed by a priest, and then absolution given by the priest. The sacrament of the Eucharist is the most central aspect of Roman Catholicism. In it, Roman Catholics believe that the substance of the bread and wine is changed into the substance of the body and blood of Jesus Christ, a doctrine known as transubstantiation. Lay people receive the life of Christ through partaking of the Eucharist, and the priest sacrificially offers Christ for the remission of sins in the liturgical celebration, commonly called the Mass. A fifth sacrament is the anointing of the sick. This sacrament is most frequently given to the dying for a final forgiveness of sins. Marriage is considered a sacrament, as is Holy Orders, the ordination to diaconate, priesthood, or episcopacy. In most cases, Roman Catholicism requires priests to remain celibate.

Roman Catholicism believes in prayer to the saints, with a particular emphasis on the saints’ active participation in the ongoing sanctification of believers in this life and ability to share even their merits. This doctrine, along with the doctrine of indulgences, became central to the related doctrine of purgatory. Purgatory is the belief that after death Christians must be further sanctified through a “cleansing fire” in an intermediate state after death before they go on to enjoy the “beatific vision,” or eternal communion with God.17

Roman Catholics recognize the sixty-six books of the Old and New Testament as canonical Scripture. They also accept fourteen “deuterocanonical” books, but as fully canonical. The authoritative “Deposit of the Faith,” for Roman Catholics, is comprised of both written Scriptures and an unwritten tradition, with the final interpretive authority residing in the formal declarations of the teaching magisterium of the church under the leadership of the bishop of Rome.

Learn more about the Roman Catholic faith:

A Guide to the Writing of Pope Benedict XVI

Why We Believe in the Real Presence: An Exposition of Luke 22:14–20

Catechism of the Catholic Church (U. S. Edition with Glossary and Index)

Regular price: $10.99

Catholic libraries:

The Protestant Reformation

Most of the other Christian denominations come out of the Protestant Reformation, which began in 1517. The major event was Martin Luther’s 95 Theses, which challenged the practice of selling indulgences.18

This kicked off two centuries’ worth of religious controversy and social disruption. The result was a new religious landscape in the West, with four or five new movements which we now refer to as denominations.

Lutheranism

Lutheran churches are those bodies which followed the teaching of Martin Luther and went on to affirm the Book of Concord. These churches had a regional and ethnic component, as they were all located in German territories and Scandinavian countries. But they originally also had a coherent doctrinal unity. The central teaching of the Lutheran churches is the doctrine of justification by faith alone, by which a Christian is declared righteous in the sight of God because of the work of Christ received by faith. This is the fundamental ground of the believer’s salvation. Since this affirmation quickly brought Luther into conflict with the authoritative tradition of the medieval church, a second important doctrinal distinctive became the authoritative role of the Scriptures, above even church tradition. This has come to be known as the doctrine of sola scriptura. Only the Scriptures can be the ultimate ground for establishing doctrine. Along with all Protestant groups, Lutherans affirm the sixty-six books of the Old and New Testament to be the canon of Scripture. The apocryphal books are allowed to be read, but are not to be used to establish doctrine.

Lutherans reject many aspects of the earlier Western Christian tradition, such as the system of penance and the role of ascetic piety. They argue that these had been harmful developments which threatened biblical doctrine. At the same time, Lutherans retain many features of the church’s liturgy and calendar, they continue to insist on the necessity of an ordained clergy (though without bishops), and they strongly emphasize the sacraments of baptism and the Lord’s Supper. Lutherans believe that baptism washes away sin and begins the new life of the Christian.

The twentieth century saw many changes within Lutheran churches. The largest segment, referred to as “mainline Lutheranism” or “liberal” Lutheranism, has followed other modern Protestant groups in criticizing basic elements of the Christian tradition and orthodoxy, including (especially) views of Scripture and human sexuality. In response, conservative groups have re-asserted a more traditional and confessional form of Lutheranism. The largest traditional Lutheran body in the United States is the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod.

A major hallmark of Lutheran theology and identity is their conviction that the real body and blood of Christ are present in the Lord’s Supper. Differing somewhat from Roman Catholicism, Lutherans do not teach that the bread and wine transform into the body and blood of Christ but rather that the body and blood are present “under” the bread and wine or “along with” and “through” the reception of the elements. This was a major point of division between the Lutheran churches and the other Reformation bodies which came to be known as Reformed churches.

Learn more about the Lutheran tradition:

The Spirit of Christ: The Holy Spirit in Lutheran Tradition

Recovering Martin Luther’s Catechism: What Protestants Forgot

Lutheran libraries:

Reformed churches

The Reformation gave rise to at least two broad Protestant groups. Alongside the Lutherans, the Reformed churches initially emerged through the ministry of Huldrych Zwingli in Switzerland. A broader collection of leaders and various regional centers soon followed. Reformed churches spread across Switzerland, the Netherlands, western Germany, parts of Poland and Hungary, as well as in England and Scotland. Other key leaders were Martin Bucer, John Calvin, Heinrich Bullinger, and John Knox.

Initially these church bodies differed from the Lutherans over the doctrine of the Lord’s Supper. Zwingli took a radical view, appearing to deny any special or unique presence of Christ in the sacrament. The later Reformed consensus affirmed a “spiritual presence,” denying that the substance of the body and blood of Christ is conferred within or under the elements of the bread and wine, but rather that the Holy Spirit presents the body and blood of Christ to the believer by faith in the action of receiving the bread and wine. The Reformed denied that this could be done apart from an active faith.

After their divergence from the Lutherans, the Reformed churches began to develop other important distinctives. Many people today associate them with “Calvinism.” Reformed churches tended to take on a more minimal liturgy and church calendar. The Church of England and the Reformed churches in Hungary and Romania are exceptions, and both of these groups also retained bishops. The majority of Reformed churches, however, are governed by elders working together in synods or presbyteries.

Reformed churches also tended to organize along national lines. While recognizing one another as having a broad doctrinal agreement, each Reformed church tended to write its own confession of faith. Swiss and German churches had the Helvetic Confessions and the Heidelberg Catechism. The Dutch Reformed churches had the Belgic Confession, which they paired with the Heidelberg Catechism and the Canons of the Synod of Dort. Other European nations also had their own Reformed confessions. This contributed to the character of Reformed churches as a broad federation or fellowship of ecclesiastical bodies. The Puritan and Presbyterian churches emerged later, from within the context of the British church establishment. As such, they defined themselves in opposition to “Anglican” distinctives and thus took on a more critical relationship to practices like liturgy and the church calendar. They subscribe to the Westminster Confession of Faith and its accompanying Larger and Shorter Catechisms.

Reformed churches agree with the Lutherans on the canon of the Holy Scripture and also affirm the doctrine of sola scriptura.

Learn more about the Reformed tradition:

What Is Reformed Theology? Its Roots, Core Beliefs & Key Leaders

What Is Calvinism? A Simple Explanation of Its Terms, History & Tenets

Westminster Confession of Faith | WCF (including the Larger and Shorter Catechisms, American Revision, 3 vols.)

Regular price: $17.99

Reformed libraries:

The Anabaptist churches

A third group that came out of the Reformation are the Anabaptists. Their differences from both the Lutheran and Reformed churches are so basic that they are not considered Protestant in the historical sense. Many of the Anabaptist groups were not institutionally unified, and so historians will often speak of the entire spectrum as “the radical Reformation.” Radical reformation leaders and movements developed in both Lutheran and Reformed territories. The two most significant of these groups are the Mennonites and the Amish.

Anabaptist groups believe that the church should be separate from the world in both a moral and a socio-political sense. Anabaptists historically did not participate in the political life of their nations, and they usually lived together on communal property away from the established cities. Anabaptists would not hold political office nor fight in the military, believing that the teachings of Christ in the Sermon on the Mount forbade both.

The name “Anabaptist”—first applied to them, as with a number of denominational names (“Methodist,” “Quaker”), by their critics—derives from their rejection of infant baptism. Anabaptists ceased the practice of baptizing infants, and they required persons who had been baptized as infants to be baptized again upon a profession of faith. In the sixteenth century, this was seen as destabilizing for both the church and the state. Because of this, the Anabaptists were victims of state persecution in every country in Europe.

Anabaptists share their views of the canon of Scripture with the Lutherans and the Reformed, but Anabaptists went further in disregarding earlier church creeds. Some Anabaptists began to reject the doctrine of the Trinity or to redefine how they understood Christ’s two natures, but most retained a basic orthodox theology of the Trinity and Christology, though without the precise formulations.

Because of their separatist and communalist beliefs, traditional Anabaptists exist as much as ethnic groups as churches. Many continue to speak distinct languages or dialects.

Learn more about the Anabaptist tradition:

Spiritual and Anabaptist Writers: Documents Illustrative of the Radical Reformation

Regular price: $9.99

The Church of England and Anglicanism

The Church of England has a complicated relationship to the Reformed churches. It originally split from Roman Catholicism over political disagreements, namely between Henry VIII and the Pope over his right to an annulment and remarriage. This quickly moved to the question of authority over the clergy in England, with Henry declaring himself to be head of the church in that realm. The theological disagreement at this point was minor. But at the same time, Lutheran ideas had influenced many of the English nobility, as well as Archbishop Thomas Cranmer. Cranmer moved from a Lutheran to a Reformed theology over the course of his career. When Henry died, Cranmer was able to more fully reform the Church of England through the Articles of Religion and Book of Common Prayer. These documents promoted the older catholic doctrines of the Trinity and person of Christ, but they also taught the Reformation doctrines of justification by faith alone and sola scriptura.

The Church of England was a national church, and as such it did not see itself as a subset of another denomination or movement. Its theology was largely consistent with that of the Reformed churches, but it retained the government of bishops, as well as a distinctive approach to liturgical ceremony and the church calendar—as well as practices like fasting. Cranmer abolished the monasteries, but he envisioned the daily offices in the Book of Common Prayer as ways to give all Christians a sort of semi-monastic piety. There are some ways that it more resembles Lutheranism and some ways that it more resembles the Reformed churches. Still, in other ways the Church of England had a unique set of practice and identity.

Since the Church of England was directly united to the life of the English nation, it underwent significant controversy and development along with the changes of governments and especially with the seventeenth-century English Civil War. From Henry’s Catholicism without a Pope, it swung to a more continental-Reformed mode under Edward VI. With Queen Mary, the Church was violently taken back into Roman Catholicism, and then with Elizabeth it returned to Reformation Protestantism—but with a commitment to unity and stability. Both Queen Elizabeth and then King James after her held out hope for reuniting the Protestant churches, at least under a sort of political confederation. While this never materialized, the aspiration explains some of their politics of moderate toleration between different Protestant impulses.

After the English Civil War and the restoration of the monarchy, the church body and culture which we now think of as “Anglicanism” was fully established. Its government and organization is led by bishops who then ordain priests (also called “presbyters”) and deacons. It proclaimed its standard of doctrine in the 39 Articles of Religion, and its standard for worship in the 1662 edition of the Book of Common Prayer.

As the Church of England sent missionaries to new countries, especially the United States, Canada, Australia, and various African nations, each regional collection of churches began creating its own organizational structure, which they called provinces. Each province was largely independent, but they began meeting together in a conference in 1867. The churches who attended this conference became known as the worldwide Anglican Communion, or simply “Anglicans.” The Church of England, then, was one province. The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America (later simply “the Episcopal Church”) was another. All churches in the global communion can be referred to as Anglicans.

In the twentieth century, a division arose within this communion of churches over traditional sexual ethics and ministerial ordination. A majority of traditional Anglican churches formed a distinct conference, called the Global Anglican Future Conference (GAFCON), which has been attempting to “reset” the global communion along the lines of what it understands to be traditional and orthodox teaching and practice. This was most recently announced through the 2023 Kigali Commitment. The Anglican Church in North America (ACNA) is the ecclesiastical representative of this form of Anglicanism in the United States, Canada, and Mexico. Its bishops are independent of the Episcopal Church, and look to the global Anglican world for guidance and unity.

Learn more about the Anglican tradition:

Anglican History: Reformed, Catholic, or Confused?

Why Anglicans Study the Bible in Light of Tradition

Anglican libraries:

Modern denominations

The Puritan movement originally developed within the context of the Church of England as an interest movement which aspired for further reform. It eventually produced separate ecclesiastical bodies which would go on to become separate denominations. The Puritans eventually gave rise to the Presbyterians, the Congregationalists, the Baptists, and the Quakers. As these groups moved to North America, they were able to achieve independence and an enduring status. It was really their apparent permanence and success that created our modern understanding of multi-denominational Christianity.

Presbyterians

Presbyterians retained most of the theology and history of the Church of England, at least that of its most Reformed members, but they argued against a uniform liturgy. In place of bishops, Presbyterians believed that the church should be governed by presbyters, including both ordained ministers and lay elders, meeting together in presbyteries and synods. Presbyterians made up the majority of ministers and theologians who drafted the Westminster Confession of Faith. Initially, they desired for this confession to replace the 39 Articles of Religion and become the confessional standard for the Church of England. This was never achieved, though the Westminster was received and ratified by the Church of Scotland.

As they moved to America, the Presbyterians became a central mainline denomination. John Witherspoon, professor to many of the founding fathers, was a leading Presbyterian minister. Princeton College and Seminary was an important Presbyterian educational institution. While Presbyterians typically retained their earlier Reformation doctrines, they began to approximate more modern evangelical attitudes about church and culture. Divisions arose between those Presbyterians who continued to affirm the doctrine of the Westminster Confession of Faith, especially the doctrine of predestination, and those who largely replaced it with general ideas common to American evangelicalism and its often revivalist theology. This divide would ultimately lead to permanent divisions, with a modernist or “liberal” Presbyterianism and a “fundamentalist” or “confessional” Presbyterianism.

Learn more about Presbyterianism:

What Is Reformed Theology? Its Roots, Core Beliefs & Key Leaders

Westminster Confession of Faith | WCF (including the Larger and Shorter Catechisms, American Revision, 3 vols.)

Regular price: $17.99

Congregationalists and post-Puritan churches

Congregationalists were very similar to Presbyterians, with the major difference being their form of church government. Congregationalists argued that each congregation should be autonomous. Many Congregationalists eventually left England, first for Holland and then for New England in North America. No longer marginalized by an establishment church, each of these dissenting groups could claim to be a mainstream ecclesiastical body. The Congregationalists became the predominant expression of Christianity in early New England. Some of their descendants remain as historic Congregationalist churches to this day. Others have merged with other various European groups to form the United Church of Christ.

English Puritanism also produced several groups which moved beyond the boundaries of traditional Christian orthodoxy. Unitarianism and deism first began as intellectual movements within Puritan and dissenting bodies. Eventually the Unitarians became their own denomination. The Quakers, or Society of Friends, also began as a Puritan movement but quickly rejected many basic Christian doctrines. While a small denomination today, the Quakers were extremely important in the eighteenth century, in England and especially the United States.

Learn more about Congregationalism:

A History of the Unitarians and the Universalists in the United States

Regular price: $12.49

Baptists

The Baptists developed out of the Puritan and Congregationalist churches.19 The major distinguishing feature of the Baptists was their rejection of the practice of infant baptism. Baptists believe that an active profession of faith is necessary in order for a person to be baptized. The relationship between the English Baptists and the earlier Anabaptist movements on the continent is disputed.20 Most of the English Baptists viewed themselves as closer relations to the Puritan Congregationalists, but their similarity with the Anabaptists was noted in the seventeenth century, and some Baptists attempted to merge with Mennonite groups for a brief period while in exile on the continent.21

The Baptist movement originally divided along two lines. The first line became known as the the General Baptists. These adopted more of an anti-Calvinist theology and went on to blend with certain Methodist and broadly “evangelical” ideas in America. Particular Baptists, appearing about twenty years later,22 retained more of a Reformed and Calvinistic identity, disagreeing with other Reformed Christians mainly on the question of baptism. These two lines of early Baptist churches existed independently of one another and indeed had sharp disagreements over a variety of doctrinal and ecclesiological points. A third line of Baptists would emerge about a generation later, the Seventh-Day Baptists. These were always much smaller in number but some would later join with other groups, giving rise to the Seventh-Day Adventists.23

As they moved to America, the Baptist churches eventually became the largest Protestant denomination in the United States. Baptist teachings on religious liberty, convictions they brought with them to America, as well as their early participation in the First Great Awakening contributed to their growth in the new country.24 Because of their congregationalist governmental structure and emphasis on the autonomy of the local church, Baptists began to have a tremendous amount of diversity. Some retained their historic connection to the British Puritan churches, but many became thoroughly American. With the diversity among Baptists, new groups began to break away from them, while continuing Baptist churches themselves developed in various ways. The largest, the Southern Baptist Convention, moved in what could be described as a more conservative and even confessional direction, while other important Baptist groups made different developments.25

Learn more about Baptist tradition and thought:

What Do Baptists Believe? An Intro to Baptist Theology & Roots

Baptist Bible Study: History, Beliefs, Major Figures, and Resources

Credo-Baptist, Paedo-Baptist, and Other Views on Baptism

What Is a Reformed Baptist? Beliefs, History & Key Leaders to Know

The Second London Baptist Confession of 1689

40 Best-Selling Books for Baptists

Baptist libraries:

Methodists

The Methodists began as a movement within the established Church of England and so retained many points in common with Anglicanism.26 But their leaders emphasized a strong personal piety and individual prayers. They eventually began to promote freer styles of worship, and they crafted “methods” for encouraging religious works which would eventually come to be associated with the great revivals. George Whitefield and John Wesley were the two most famous Methodist preachers, and both were known as revival leaders.

The Methodist churches grew into one of the largest Protestant denominations in the United States. They became known for their revivals and their social activism. Much of Methodist theology followed the progress of John Wesley’s own development. Beginning as a High-Church Anglican,27 Wesley held to infant baptism and even a form of baptismal regeneration. However, he also adopted a form of Arminianism and a strict opposition to antinomianism. This caused him to place a strong emphasis on personal regeneration and upright living as necessary for salvation.28 The majority of Methodists rejected Calvinism in favor of what they called man’s “gracious ability” to follow God.29 American Methodists emphasized the growth of holiness in the life of the believer and even maintained that a believer could reach a state of perfection, where he ceased to sin.30 This quest for perfection was often simply referred to as “holiness,” and a number of new denominations formed with the term “holiness” as one of their identifiers.

Wesley and other early Methodists also practiced a form of miraculous healing. Believing in both conventional medicine and healing by prayer, Wesley understood this miraculous ministry as one facet of his understanding of entire sanctification. The Christian man would improve in holiness and in wholeness.31 This aspect of the Methodist legacy would later give rise to other denominational groups, with many moving out from North America to the rest of the world.

Learn more about Methodist tradition and thought:

What Christians Believe about the Holy Spirit: An Overview

Wesleyan libraries:

Pentecostalism

The Holiness movement stressed a dramatic internal and subjective work of the Holy Spirit in the life of the believer, as well as a ministry of miracles. This would lead to the development of Pentecostal and charismatic churches.32 The most distinctive feature of Pentecostal churches is the practice of speaking in tongues. These tongues can be either previously unknown human languages or entirely ecstatic utterances.

While Pentecostals claim a variety of inspirational sources, the first movement which insisted that “speaking in tongues always accompanied Holy Ghost baptism” arose in Topeka, Kansas, under the ministry of Charles Fox Parham.33 The early years of the Pentecostal movement were characterized by informal associations and folk piety. Thus, there is no clear marker for a single founding. Historians date the Topeka revivals from 1898 to 1900. A second founding occurred with William J. Seymour, an African American lay preacher, who took Parham’s teaching to Los Angeles, leading to the Azusa Street Revival in 1906. Azusa Street became famous, with claims of 50,000–100,000 conversions.34

Several Pentecostal denominations formed in the following years, including the Apostolic Faith, the Church of God in Christ, the Church of God, the Assemblies of God, the International Church of the Foursquare Gospel, and the United Pentecostal Church.35 Of these, the United Pentecostal Church rejects the doctrine of the Trinity, arguing instead for a “oneness” doctrine of God. The others retain basic Christian views of the Trinity and the person of Christ, as well as a mostly evangelical system of doctrine. But great diversity exists among Pentecostal theology.

In addition to speaking in tongues and miraculous spiritual encounters, Pentecostals have been noteworthy for their early integration of and empowerment of African Americans and other ethnicities. They also allowed women to preach and hold leadership positions in the church from very early on. Because of its emphasis on ecstatic and individual spirituality, Pentecostal churches are often less institutionally focused and can exist in multiple denominations, including more traditional Christian bodies.

Learn more about Pentecostalism and other charismatic denominations:

What Is Pentecostalism? Its Origin, Groups & 7 Key Elements

Pentecostal & Charismatic Bible Study: A Definitive Guide

What Is Speaking in Tongues? Should You Do It? Bible Answers

Cessationist or Continuationist: Have Some Gifts Ceased?

The Great Azusa Street Revival: The Life and Sermons of William Seymour

Regular price: $10.19

The Vine and the Branches: A History of the International Church of the Foursquare Gospel

Regular price: $13.74

Charismatic libraries:

Seventh-Day Adventists

The Seventh-Day Adventists developed out of the earlier “Millerite” movement, followers of William Miller, an American Baptist preacher who began predicting the imminent return of Christ in the 1830s. When these prophecies failed, a number of groups formed, typically calling themselves “Adventists.”

Some Baptist groups had begun observing a Saturday Sabbath as early as 1665.36 Descendants of these groups, now living in America, joined with one of the Millerite groups to form the modern Seventh-Day Adventist Church.37 This seventh-day Sabbath was their key distinctive, but many also began observing aspects of the Mosaic dietary laws or promoting vegetarianism. As they continued to develop, the Seventh-Day Adventists began to espouse more distinctive and controversial doctrines. This distinguished them from both the generic Adventist churches and the Seventh-Day Baptists.

Ellen G. White became a central figure in the development of the Seventh-Day Adventist movement. Beginning her Christian life as a Methodist, she claimed to receive visions in 1841.38 As these continued, she became an influential figure in the Millerite community. After the apparent failure of Miller’s predictions, White39 began to support emerging interpretations of biblical prophecy which would become foundational Seventh-Day Adventist doctrine. Among these was the argument that rather than a bodily return to earth in 1844, Christ entered the heavenly sanctuary at that time and began a new phase of priestly ministry.40 This gave the Seventh-Day Adventists a distinctive doctrine of salvation, which included their unique views on the Sabbath. According to this view, Christ provided a provisional forgiveness of sins at his death. He then later began actually blotting out sins in the nineteenth century, in connection with the rediscovery of the true religion, as Seventh-Day Adventists understood it. This was considered an eschatological event, marking the imminence of the Second Coming. After this blotting out of sins, Seventh-Day Adventists argue that Christ will judge according to the believer’s repentance and obedience.41

Other distinctive positions of the Seventh-Day Adventists are the ongoing “Spirit of Prophecy” and especially Ellen G. White’s status as prophet, as well as the doctrine of “the Great Controversy,” the view that before the creation of the world, Satan led a rebellion in heaven and that his rebellion has continued through erring religious institutions and especially those who oppose the doctrines of Seventh-Day Adventism.42 After White’s death, Seventh-Day Adventists debated the nature and extent of her authority.43 Notably, Seventh-Day Adventists reject the doctrine of eternal torment in hell, defining death as “sleep.”44 For much of its existence, Seventh-Day Adventism was seen as an almost distinct religion, exclusive of other Christian denominations. Subsequent revisions and developments in the second half of the twentieth century, however, have attempted to harmonize Seventh-Day Adventist doctrine with the broader evangelical Christian world.45

Learn more about Seventh-Day Adventists:

Seventh-Day Adventists libraries:

Restoration and the Churches of Christ

While any movement that attempts to “return to the first-century church” could be called a restoration movement, the term “Restorationism” usually applies to several denominations in early nineteenth-century America.46 Restorationists wanted not merely to reform the church but to restore it, often calling their goal “primitive” Christianity. E. Brooks Holifield dates the beginning of Restorationism to the church-planting activities of Abner Jones, Elias Smith, Barton Stone, and Alexander Campbell from 1801 to 1809.47 These restorationist churches claimed to reject all denominational labels and simply wanted to be called “Christian churches.”

Eventually, two major denominations would emerge from this movement: the Disciples of Christ and the Churches of Christ (though both groups reject the term “denomination”). These “Christian” churches argued that the Bible could easily be understood by ordinary people and that confessions of faith and theological arguments were largely unnecessary. Some argued against many traditional Christian doctrines like original sin and the substitutionary atonement of Christ. Barton Stone even came to reject the doctrine of the Trinity, but Alexander Campbell continued to affirm it.48 One of the most distinctive teachings of the Churches of Christ is that only baptism by immersion conveys the remission of sins. The Churches of Christ also do not generally allow musical instruments in worship, a position shared by other “primitive” groups.

Learn more about Restorationist denominations:

The Stone-Campbell Movement: The Story of the American Restoration Movement, rev. ed.

Regular price: $27.99

African American denominations

Throughout the nineteenth century, a pan-denominational movement of African American churches deserves to be mentioned. African Americans had adhered to all of the major denominations in America at the time, and some were even able to be ordained in the existing churches. Lemuel Haynes is the most famous example. He served as a Congregationalist minister in otherwise white churches in Connecticut, Vermont, and New York. Haynes taught a form of New Light Calvinism, patterned after Jonathan Edwards.49

But unfortunately, most African Americans were excluded from white churches. This led them, out of necessity, to create their own denominations. The most famous of these are the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the National Baptist Church, and the Church of God in Christ. Each of these share the core theology of their respective denominational counterparts. The National Baptists are Baptists, whereas AME churches are Methodist and COGIC churches are Pentecostal. These denominations were not born from doctrinal divisions, but rather dominant sociological and political factors in America. And precisely because of these social and political factors, the diverse Black denominations often share certain commitments with one another and distinct from their various white denominational counterparts. E. Brooks Holifield identifies two of these common distinctives as “the close relationship between theology and ethics” and a distinctive form of preaching.50 Black churches typically saw themselves as vehicles of social and even political life, and they served as an important hub for the life of their respective communities in America.

Learn more about the Black Church tradition:

6 Black Theologians from Church History You Should Know

3 Essential Resources to Learn about Black Church History

Mobile Ed: CS251 History and Theology of the African American Church (7 hour course)

Regular price: $259.99

Messianic Judaism

According to its most basic meaning, a messianic Jew is simply a Jew who believes that Jesus of Nazareth is the promised Messiah of Israel. However, a newer concept of Messianic Judaism emerged in the twentieth century. David A. Rausch explains that the term “Messianic Judaism” can cover a spectrum:

At one end of the spectrum is the Hebrew Christian movement, made up of missionary societies and individual missionaries who regard themselves primarily as an evangelistic arm of the evangelical church to the Jewish community. At the other end of the spectrum are the most orthodox of the Messianic congregations and individual adherents who regard themselves primarily as Jewish—Jews who believe that Jesus is the Messiah. Between the ends of this spectrum fall an array of congregations and individuals.

This “most orthodox … end of the spectrum” seeks to take on many features of orthodox or rabbinic Judaism. Its congregations refer to themselves as synagogues. Its ministers refer to themselves as rabbis. Some adherents attempt to follow the Mosaic dietary laws and keep a full Saturday Sabbath, along with the traditional Jewish festivals. Though certainly a distinct form of Christianity, Messianic Judaism is a Christian denomination and is not recognized by the overwhelming majority of traditional Jews.

Learn about Messianic Judaism:

Messianic Judaism: A Modern Movement With an Ancient Past (A Revision of Messianic Jewish Manifesto)

Regular price: $13.99

Introduction to Messianic Judaism: Its Ecclesial Context and Biblical Foundations

Regular price: $26.99

Messianic Jewish libraries:

20th- and 21st-century evangelicalism

In addition to the denominations already discussed, there has been a huge rise in churches which largely share the theology and ecclesiastical culture of American Baptists or Methodists, but organize themselves entirely independently and choose to avoid traditional labels. These churches are often described as non-denominational churches. Similarly, “charismatic” churches retain some features of the Holiness and Pentecostal churches, but are usually less insistent on specific doctrinal formulations or ecclesiastical forms and rules.

The early decades of the twenty-first century have also seen a change from the more traditional denominational landscape to what Mark Tooley calls “Post-Denominational America.” People are less likely to choose a church based upon formal denominational affiliation and instead look for specific congregations based on social and political factors. The most notable dividing lines have become a church’s belief about Scripture and ethics concerning sexuality, including both the relationship and roles between the sexes and the definition of marriage. This new ecclesiological framework has the potential to shake up traditional expectations and create new opportunities for ecumenical cooperation or even reunion.

A final development has been the role of the developing world and the “Global South” in the growth of Christianity and even the renewal of Orthodoxy. The fastest-growing churches today are in Africa and Asia, and “the next Christendom” will likely emerge in the Southern hemisphere.51

- Oxford English Dictionary, v.s. “denomination,” n., sense 4.

- “Dogmatic Constitution on the Church,” Lumen Gentium, sec. 67, 69.

- Belgic Confession, Art. 29.

- Westminster Confession of Faith 25.4.

- 39 Articles of Religion, Art. 34.

- Robert Frykenberg, Christianity in India: From Beginnings to Present (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 92–102.

- A. Christian van Gorder, Christianity in Persia and the Status of Non-Muslims in Iran (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2010), 24.

- Roman Malek, ed., Jingjiao: The Church of the East in China and Central Asia (London: Taylor & Francis, 2021), viii.

- Hans-Joachim Schoeps, Jewish Christianity, (Minneapolis, MI: Fortress Press, 1969); Justo Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity, vol. 1. (New York: Prince Press, 2007) 22.

- Peter Brown, “The Rise and Function of the Holy Man in Late Antiquity,” The Journal of Roman Studies 61 (1971): 80–101.

- Gonzalez, Story of Christianity, 1:231–47.

- See Gerald Bray’s explanation of this controversy.

- Andrew Louth, The Church in History (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2007), 3:189–92, 311–16.

- Letter 1: On Confession, 11.

- See Canon 85 of the Pedalion, 145; Eugen J. Pentiuc, The Old Testament In Eastern Orthodox tradition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 119–33.

- ” … by divine ordinance, the Roman church possesses a pre-eminence of ordinary power over every other church, and that this jurisdictional power of the Roman pontiff is both episcopal and immediate.” First Vatican Council, Session 4, Chapter 3, Point 2.

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1031.

- Gonzales, Story of Christianity, 2:22.

- William Henry Brackney, The Baptists (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1988); Leon McBeth, The Baptist Heritage (Nashville, TN: B&H Academic, 1987), 21.

- Robert Torbet, A History of the Baptists (King of Prussia, PA: Judson Press, 1987), 25–29, 35–37; William Brackney, A Genetic History of Baptist Thought (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2004), 12; Matthew Bingham, Orthodox Radicals: Baptist Identity in the English Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Brackney, Baptists, 4; Torbet, History of the Baptists, 35.

- Torbet, History of the Baptists, 40.

- Brackney, Baptists, 6–7, 12.

- Brackney, Baptists, 10, 12–13; Torbet, History of the Baptists, 221, 243.

- Brackney, Baptists, 20–21; Brackney, Genetic History of Baptist Thought, 43–63.

- David Hempton, Methodism: Empire of the Spirit (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005), 18–29.

- Hempton, Methodism, 14.

- Karen B. Westerfield Tucker, “Sacraments and Life-Cycle Rituals” in The Cambridge Companion to American Methodism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 141–44.

- E. Brooks Holifield, Theology in America: Christian Thought from the Age of the Puritans to the Civil War (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003), 264.

- Holifield, Methodism, 270–71.

- Candy Gunther Brown, “Healing,” in The Cambridge Companion to American Methodism (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 227.

- Gonzalez, History of Christianity, 2:255.

- Grant Wacker, Heaven Below: Early Pentecostals and American Culture (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 5.

- Wacker, Heaven Below, 6.

- Wacker, Heaven Below, 6.

- Brackney, Baptists, 7.

- Gonzalez, History of Christianity, 2:255–56.

- Ronald L. Numbers, Prophetess of Health: A Study of Ellen G. White (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2008), 51.

- Her last name at the time was Harmon; she would marry leading Adventist minister James White in 1846. Notably for the time, Ellen White’s authority exceeded that of her husband in the Seventh-Day Adventist community.

- P. Gerard Damsteegt, Foundations of the Seventh-Day Adventist Message and Mission (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1977), 127–35; M. Ellsworth Olsen, A History of the Origin and Progress of Seventh-Day Adventists (New York: AMS Press, 1972), 186–87.

- E. G. White, The Great Controversy between Christ and Satan during the Christian Dispensation, 11th ed. (Oakland, CA: Pacific Press, 1889), 485–86.

- White, Great Controversy, 582–92.

- Numbers, Prophetess of Health, 352–54, 356–66; for example, “The impression was conveyed that practically every word that she spoke, and every letter she wrote, whether personal or otherwise, was a divine inspiration. Those things make it awfully hard for our teachers and ministers,” 365.

- General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists, Seventh-day Adventists Believe… (Review and Herald Publishing Association, 1988), 352–58.

- Rolf J. Pohler, Continuity and Change in Adventist Teaching (Switzerland: Peter Lang, 2000), 124–34.

- The stricter sorts of Seventh-Day Adventists are also restorationist in the most basic sense, as they claim to be a re-founding of the true church after centuries of apostasy. Mormons, though not orthodox Christians, are also restorationist.

- Holifield, Methodism, 291–92.

- Holifield, Methodism, 305.

- Holifield, Methodism, 309.

- Holifield, Methodism, 312–13.

- Philip Jenkins, The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).