“What is Calvinism?” Any attempt to give just one answer is sure to be wrong. Calvinism is not a church or a denomination. Calvinism is not even (just) a system of doctrine. Instead, Calvinism is a broad religious tradition with certain shared views and points of emphasis. It is doctrinal, churchly, and activistic. Calvinism teaches that the glory and sovereignty of God should come first in all things. Calvinism believes that only God can lead his church—in preaching, worship, and government. And Calvinism expects social change as a result of the proper teaching and discipline of the church.

In this article:

- Definitions of “Calvinism”

- Calvinism and Reformed theology

- Predestination and God’s glory

- The Calvinistic view of the church

- Calvinism, society, and culture

- The theology of Calvinism

- Hyper-Calvinism

- Moderate Calvinism

Definitions of “Calvinism”

The first thing you have to know is that almost nobody who we now think of as being a “Calvinist” wanted to be called that at the time. Calvin himself never claimed to be creating a unique system of theology, and he never defined “Calvinism.” Scholars agree that there is no single “most important” doctrine that Calvin uses to organize his theology. None of Calvin’s students argued that they were members of a “Calvinist” school of doctrine.

The name “Calvinist” was first used as a put-down by Lutheran theologians in their debates over the Lord’s Supper.1 The famous English Reformed theologian William Perkins, writing in 1592, said that it would be inappropriate to take the name “Calvinist.”2 Even as recently as nineteenth-century America, you can find Robert L. Dabney, the Southern Presbyterian, writing, “We Presbyterians care very little about the name Calvinism.”3 Most contemporary scholars of John Calvin and Reformed theology dislike the term and argue that it should not be used in scholarly contexts.

Since all this is the case, we have to admit that there is no universal standard that we can use to define and judge “Calvinism.” Different from “Lutheranism,” there are no churches or denominations that call themselves “The Calvinist Church.” While you will come across expressions like “hyper-Calvinism” and “moderate Calvinism,” there is no singular Calvinist confession of faith, and so any claim to “true Calvinism” will always be debated.

There are both paedobaptists and credobaptists who call themselves “Calvinists.” Presbyterians and congregationalists use the name. There are Calvinistic Anglicans. Calvinism has even become popular among a range of North American evangelicals who also affirm the continuation of charismatic gifts, contemporary worship styles, and modern views of arts and culture.

So instead of trying to find a single idea that defines Calvinism, we would do better to understand it as a collection of common theological ideas, views of church organization and law, and expectations about Christian living and social change.

Calvinism and Reformed theology

A common argument is that Calvinism is a synonym for Reformed theology. Reformed theology is one of the two main varieties of traditional Protestant Christianity descending from the sixteenth-century Reformation. The other is Lutheranism. Ulrich Zwingli is often claimed as the founding father of Reformed theology. The truth is more complicated.4 While Zwingli was a major leader and even groundbreaker, there was an international collection of sympathetic clerics and theologians who worked together to form what we know as Reformed theology. By anyone’s telling, however, John Calvin is clearly in the second generation of Reformed thinkers. After being forced to flee France, Calvin finds in both Switzerland and Strasbourg pre-existing Reformed churches and communities.

Another challenge for those wishing to merely identify “Calvinism” with Reformed theology is that the latter is more closely connected to churches and particular confessions of faith. Certain views of the divine covenants, as well as of infant baptism, are usually argued to be central to Reformed theology. “Calvinism,” on the other hand, is regularly applied to groups who hold contrary views on these doctrines.

A third complication is that many Anglicans happily accept the title “Reformed,” but shy away from the name “Calvinist.” Because of debates over church government, liturgy, vestments, holidays, and revolution, many Anglicans associate Calvinism with the Puritan movement. And so, while it is understandable to connect Calvinism and Reformed theology, the two terms have enough of a different connotation to be defined differently. Reformed theology refers to confessions of faith and formal church bodies. Calvinism is more of a collection of ideas, priorities, and social movements.

What Is Reformed Theology? Its Roots, Core Beliefs, and Key Leaders

Predestination and God’s glory

The most common definition of Calvinism has to do with the doctrines of predestination and divine election in salvation. This is often described as a unique system of theology and associated with the 1619 Synod of Dort. While the Synod of Dort was an important international council, it was only regional in its authority. It was also limited in its task. It did not try to explain an entire system of theology. Instead, it responded to five theological positions posed by the students of Jacob Arminius. This is where we get the Five Points of Calvinism (see below).

But the Synod of Dort also has to be understood as existing within a larger tradition. Calvinist theologians had existed long before Dort. John Calvin himself died in 1564. The Heidelberg Catechism was published in 1563. The English Lambeth Articles, commonly described as Calvinistic, were released in 1595. Many Calvinistic groups have never formally adopted Dort’s canons. The Westminster Confession of Faith has had a much greater and more direct influence on Calvinism in English-speaking countries. While it was drafted after the Synod of Dort, its chapter on predestination closely resembles the Irish Articles, which were published four years before Dort.5 So even though the organizing of Calvinism into five points comes from the Synod of Dort, the larger idea of Calvinism is older and broader.

John Calvin certainly did write about predestination and election. These themes appear in his Institutes of the Christian Religion6 and also in his controversial writings against Albert Pighius on the freedom of the will and eternal predestination. Several of Calvin’s students and successors continued to write on these themes. Two of the most famous were Theodore Beza and Girolamo Zanchi. While these doctrines were never presented by Calvin as the central or most important doctrines, it did become common for critics to begin attacking them as “Calvinism.”7 When Charles Spurgeon wrote “A Defence of Calvinism” in the middle of the nineteenth century, he meant the doctrines of predestination and divine election.8

The early twentieth century American Presbyterian Theologian B. B. Warfield did not believe that Calvinism should be reduced to predestination. “The doctrine of predestination is not the formative principle of Calvinism,” he wrote.9 Instead, Warfield argued that Calvinism was “an overwhelming vision of God … , a complete world-view, in which [salvation] becomes subsidiary to the glory of the Lord God Almighty.”10 For Warfield, this “world-view” then creates “a particular theology,” “a special church organization,” and even “a social order.”11 This way of understanding Calvinism became widespread in the late-nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The school of theology called “Neo-Calvinism” agreed. Two of its most famous representatives were Abraham Kuyper and Herman Bavinck. Calvinist figures in the liberal “mainline” made similar arguments.12

The Calvinistic view of the church

A second way that Calvinism distinguished itself historically was its particular view of the church. Calvinism maintained that the church was a divine creation. As such, it was not dependent upon the human will, whether in terms of tradition or the civil rulers. This caused Calvinism to have a more specific view of church government and polity. Typically, Calvinists argued against bishops and for lay-elders. Calvinists also wanted the ministry of the church to have an important measure of independence from the civil government. This did not mean the more modern vision of a separation of church and state, but it often did mean that the pastors of the church viewed themselves as prophetic critics of the political rulers. Calvinism also tended to teach a greater right of resistance and even revolution in the face of tyrannical government. All of this was held together under the notion of divine sovereignty. Quoting the book of Acts, Calvinists would say, “We ought to obey God rather than men” (Acts 5:29).

This aspect of Calvinism is complicated by the fact that John Calvin did not teach all of it. While he did teach the concept of lay-elders and jealously guarded the clergy’s right of excommunication, he did not believe that the Bible prescribed every point of church government. “For we know that every Church has liberty to frame for itself a form of government that is suitable and profitable for it, because the Lord has not prescribed anything definite,” he wrote.13 Calvin also limited the right of resistance to lesser magistrates. He did not believe that private citizens could ever rebel against their political leaders.

Still, this emphasis of divine church government quickly became associated with Calvinism. When Richard Hooker wrote against the stricter Puritans, he noted that they had turned Calvin’s books into “almost the very canon to judge both doctrine and discipline.”14 The Scottish Presbyterians made similar arguments to the English Puritans, especially in their quarrel with King James. French Huguenots were also considered “Calvinist,” and they promoted a particular version of resistance theory that would become influential for later political movements.15 Certain American founding fathers could appeal to this Calvinistic heritage, even if some of the same founders were not personally orthodox Christians.

Critics of Calvinism have accused this view of government of being separatistic, oppositional, and inclined to rebellion. Proponents argue that it safeguards the liberty of the church and the liberty of the Christian conscience. They also argue that it puts the teaching ministry of the church in the greatest position of social influence.

Calvinism, society, and culture

A third identifying feature of Calvinism has been its social activism and desire to apply religious convictions to everyday life. This theme is most famously associated with Abraham Kuyper.16 Kuyper wrote, “Calvinism made its appearance, not merely to create a different Church-form, but an entirely different form for human life, to furnish human society with a different method of existence, and to populate the world of the human heart with different ideals and conceptions.”17 Kuyper pressed this argument in a very particular way, arguing that Calvinism represented its own sort of “science” and “life-system.” Much of this has been criticized by later scholars. But Kuyper’s influence was huge. Inspired by him, twentieth-century Calvinists formed new political movements, founded schools, and advocated for a wide range of social issues.

Kuyper was not the first Calvinist to derive a sort of activism in theology. In 1633, the English poet George Herbert wrote,

Nothing can be so mean,

Which with his tincture (for thy sake)

Will not grow bright and clean.

A servant with this clause

Makes drudgery divine:

Who sweeps a room as for Thy laws,

Makes that and th’ action fine.18

Herbert is there speaking of the way that understanding God’s principles and laws transforms the perception and meaning of even the lowliest task.

This activistic impulse in Calvinism is what the famous sociologist Max Weber was interacting with in his book, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. When Weber spoke of “Protestants,” he primarily meant Calvinists. Calvinists were also central to the eighteenth and nineteenth century “evangelical” movement, which emphasized social activism and reform. In 2014, John Piper described “the New Calvinism” as being “culture-affirming” and as promoting “missional impact on social evils.”

This vision of Calvinism transforming society and culture is widely debated. Many scholars and historians dispute the legitimacy of crediting (or blaming!) it on John Calvin or Reformed theology. But the connection has persisted. However complicated, there does seem to be a common family resemblance between Calvin’s leadership over a city-state in Geneva, the English Puritans, American evangelicals, and Dutch Neo-Calvinists. Often, when Reformed thinkers reject the title “Calvinistic,” it is this feature that they wish to avoid.

The theology of Calvinism

The most common meaning of Calvinism is the doctrinal one. A Calvinistic theologian is someone who promotes the doctrines of predestination and divine election. But we need to be careful with this understanding. Predestination and election were central themes in the fourth-century church theologian Augustine of Hippo. They show up in medieval theologians like Anselm of Canterbury (11th cent.), Thomas Aquinas (13th cent.), and Thomas Bradwardine (14th cent.). Before John Calvin, both Martin Luther and Ulrich Zwingli taught predestination and election. When people mean Calvinism, they mean a specific presentation and emphasis, as well as certain particular points about fore-ordination to salvation and damnation, as well as the nature and extent of the saving death of Christ.

Key doctrinal terms

In discussions about Calvinism, it is important to define and distinguish key terms. Predestination is not simply the idea that God knows all things. Rather, theologians call that concept divine foreknowledge or prescience. All orthodox Christians believe in divine foreknowledge. “Even before a word is on my tongue, behold, O Lord, you know it altogether” (Ps 139:4). A similar doctrine is divine providence. Providence refers to the fact that God not only knows all things but actively governs them.

- “Are not two sparrows sold for a penny? And not one of them will fall to the ground apart from your Father.” (Matt 10:29)

- “And we know that for those who love God all things work together for good, for those who are called according to his purpose.” (Rom 8:28)

Again, all orthodox Christians affirm divine providence.

Predestination is closely related to questions of free will, but predestination does not necessarily mean that humans lack free will. In fact, the Westminster Confession of Faith teaches,

God, from all eternity, did, by the most wise and holy counsel of his own will, freely, and unchangeably ordain whatsoever comes to pass: yet so, as thereby neither is God the author of sin, nor is violence offered to the will of the creatures; nor is the liberty or contingency of second causes taken away, but rather established. (WCF 3.1)

Calvinists believe that before Adam’s fall into sin, mankind had a free will and was able to choose the good. Free will has been lost because of sin, not because of divine sovereignty.19 “Those who are in the flesh cannot please God” (Rom 8:8).

The loss of free will due to sin was taught by Augustine of Hippo and was a common doctrine in the Western Christian church until the time of the Reformation. Luther emphasized it strongly, and the doctrine is taught by the Lutheran Confessions (Augsburg Confession, ch. 18; The Formula of Concord, ch. 2). All Reformed confessions of faith teach it as well. The Calvinist view of free will is not unique. It is the common position of Lutheran and Reformed theologians.

Calvinism becomes distinctive on the topic of predestination. Predestination is the doctrine that God destines some people to believe in him, be saved, and thus spend eternity with him in blessing. Election is closely connected to this. Election is the doctrine that God chose (elected) some men to be saved.

For those whom he foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son, in order that he might be the firstborn among many brothers. And those whom he predestined he also called, and those whom he called he also justified, and those whom he justified he also glorified. (Rom 8:29–30)

The specific affirmation of Calvinism is that God does not elect any to be saved based upon his foreknowledge of their faith and repentance, or any other good works, but rather entirely out of his (God’s) free will. This number is fixed and cannot change. Every other act of salvation, then, flows from this divine choice and is dependent on it.

For by grace you have been saved through faith. And this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God, not a result of works, so that no one may boast. (Eph 2:8–9)

Lutherans agree with Calvinists about the positive affirmation of election (cf. Epitome of the Formula Concord 11.15; Solid Declaration of the Formula Concord 11.5). Where Calvinism becomes unique from Lutheranism is in its statements about reprobation, God’s choice not to elect some; and in its denial that the elect can ever fall away from justifying faith. Calvinists argue that God is active in this choice. Calvinists maintain that God does not simply predestine any person’s damnation without a basis in their own sin. But Calvinists also argue that God is active in his divine willing to either not grant the reprobate the conditions for salvation in the first place (they are not exposed to the gospel), or to not give them active faith in the gospel when it is presented. Calvinists argue that the reason for God’s decision is a mystery. They also affirm the role of secondary and intermediate causes. Believers are condemned for their own sin and their rejection of the gospel. But Calvinists maintain that the first cause, the cause behind all secondary causes, is always God. They also point to this same doctrine as the reason why true believers can never fall away. Though believers must persevere over time, God’s election will ensure that they do.

The five points of Calvinism

This teaching of divine predestination became controversial in both Britain and Holland. The Church of England explicitly teaches the initial doctrine of election shared by the Lutherans in Article 17 of its 39 Articles. It also implicitly teaches the fully Calvinistic doctrine in its assurance that the elect will “walk religiously in good works; and at length, by God’s mercy … attain to everlasting felicity.” Still, the 39 Articles do not explicitly speak of God’s role in not electing some. In 1595, the Archbishops of Canterbury and York both approved of “The Lambeth Articles,” which did explicitly speak of both divine election and reprobation. These were not approved by Queen Elizabeth I, however, and so they never became full confessional documents for the Church of England. In 1615, this same theology was articulated by the Protestant Church of Ireland in the “Irish Articles.” The most famous and detailed explanation of the theology of election, however, is in the 1619 Dutch Synod of Dort.

The canons of the Synod of Dort lay out a doctrinal answer to the five points of the followers of Jacob Arminius. These theologians are now known as “Arminians,” and “Arminianism” is frequently explained to be the opposite of Calvinism. The Arminian theologians challenged the Calvinistic orthodoxy that was already present in Holland at the time. The Synod of Dort refuted them and gave an extended defense of the Calvinistic doctrine of election.

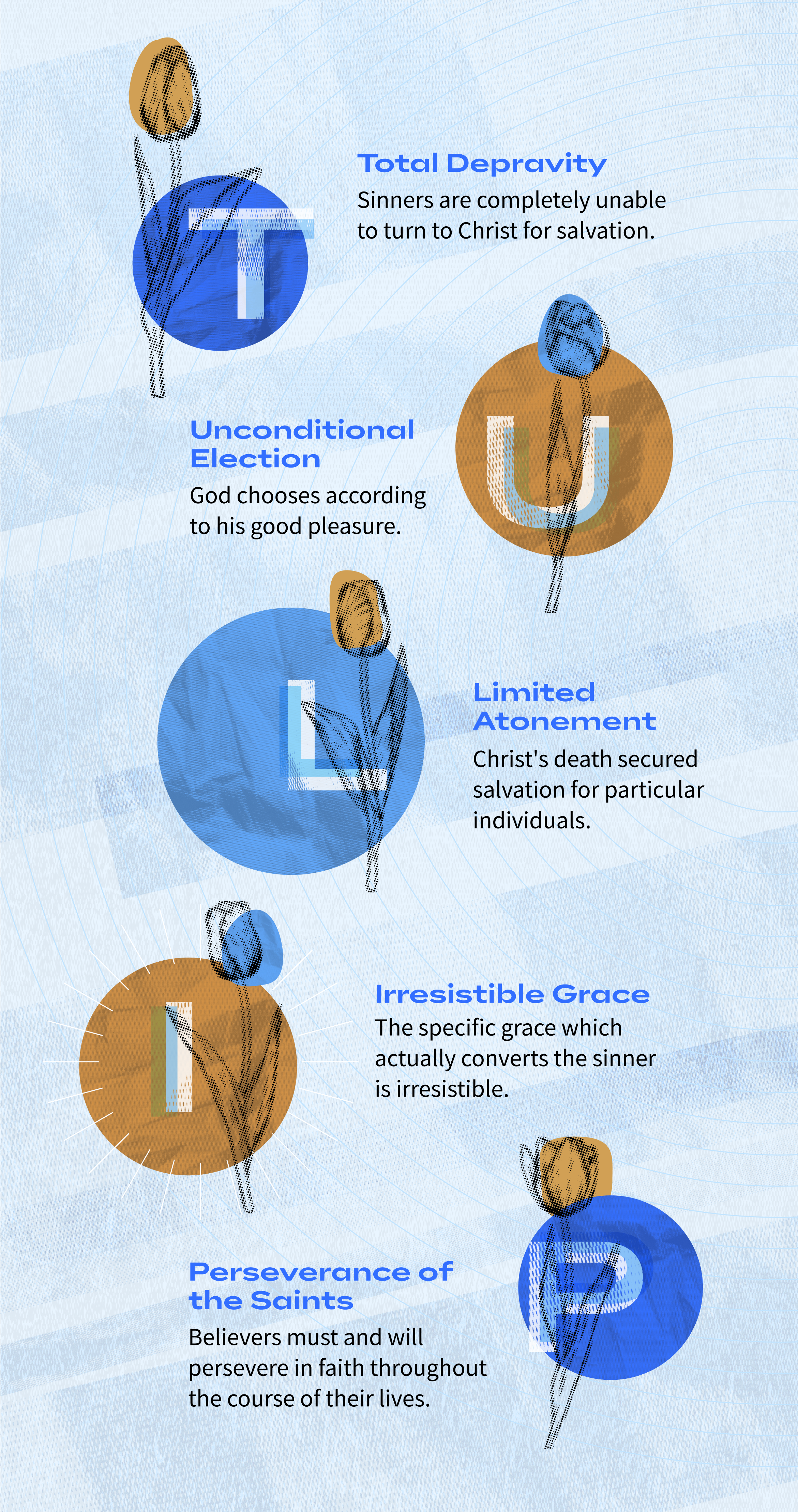

The doctrine of the Synod of Dort is commonly called “the five points of Calvinism”20 and is summarized by the acronym TULIP. This stands for:

- Total depravity

- Unconditional election

- Limited atonement

- Irresistible grace

- Perseverance of the saints

While this acronym is famous and has become a very effective teaching device, it is not a historically accurate summary of the teaching of Dort. It also uses imprecise language which is often understood in erroneous ways.

The word “tulip” is an English word, and so it would not have been a possible way for the theologians at Dort to organize their theology. The five points at Dort do not follow the order of TULIP, nor do the headings match. In fact, the canons of Dort combine the third and fourth “points” into one section. So while the Arminians may have had five points, the Calvinists at Dort walked away with only four. The term “atonement” is not even used by Dort. It is a uniquely English word, having been invented by William Tyndale in 1526.

Having said this, it is unlikely that the five points approach will fade away any time soon, and so we can still explain these points in the following way:

I. Total depravity

The doctrine commonly known as “total depravity” is better understood as “innate inability.” It is a consequence of the doctrine of original sin and the loss of free will, as discussed above.

II. Unconditional election

Unconditional election is the view discussed earlier that God alone chooses who will be saved and not based on any merit in them.

III. Limited atonement

“Limited atonement” is the most controversial of the five points, but it was not taught at Dort. Instead, the historic doctrine had to do with the divine will to apply the death of Christ to believers and effectually ensure that they would receive it and be saved, the special intent in Christ himself to bring about the redemption of the elect, and the relationship between Christ’s death on the cross and the indiscriminate offer of the gospel to call on the condition that they believe. All traditional Calvinists believed that Christ’s sacrifice possessed an infinite merit and that it was sufficient to forgive the sins of all. The canons of Dort teach that “The death of the Son of God is the only and most perfect sacrifice and satisfaction for sin, and is of infinite worth and value, abundantly sufficient to expiate the sins of the whole world” (Second Head, Article 3). They also teach that “the promise of the gospel is, that whosoever believeth in Christ crucified, shall not perish, but have everlasting life. This promise, together with the command to repent and believe, ought to be declared and published to all nations, and to all persons promiscuously and without distinction, to whom God out of His good pleasure sends the gospel” (Second Head, Article 5), and “whereas many who are called by the gospel do not repent nor believe in Christ, but perish in unbelief, this is not owing to any defect or insufficiency in the sacrifice offered by Christ upon the cross, but is wholly to be imputed to themselves” (Second Head, Article 6). The “limitation” was in the divine decree to elect and then to effectually bring about the redemption of the elect through the mediation of Christ and his death. This doctrine is therefore better described as “definite atonement” or “particular redemption.”

IV. Irresistible grace

The “I” in TULIP stands for “irresistible grace” and is also easily misunderstood. It does not mean that all of God’s grace is irresistible but only that the specific grace which actually converts the sinner is irresistible. This grace “goes before” any action of the human will. But after this initial grace, the human will is changed and thus works together with the divine. Calvinism teaches that, because of divine election, this process will always be effectual. It is not based upon the works of the human will.

V. Perseverance of the saints

Finally, the perseverance of the saints teaches both that true believers must persevere in faith throughout the course of their lives and that they certainly will because of God’s gracious election.

Hyper-Calvinism

Hyper-Calvinism is an exclusively critical term. Opponents of Calvinism consider all Calvinists to be hyper-Calvinists. But within Calvinism, hyper-Calvinism typically refers to those who deny the freedom and contingency of secondary causes—especially theologians who argue that God foreordains men to damnation apart from first considering their sin. Hyper-Calvinism is also applied to those who deny that the gospel should be preached indiscriminately to everyone.

Moderate Calvinism

Moderate Calvinism is not really a distinctive school within Calvinism. Typically the expression means those theologians who affirm predestinarian theology but who decline to give it a central or primary emphasis. They instead balance it with doctrines like the sacraments and ordinary means of grace. Moderate Calvinists are also frequently said to deny “limited atonement,” but this depends on the false understanding of atonement which we attempted to correct above. Theologians frequently considered to be “moderate Calvinists” were present at both Dort and Westminster and defended the theology of both confessional documents. The majority of Calvinistic Anglicans could be considered “moderate Calvinists.” The same is true for the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century German Reformed theologians and the seventeenth-century English Presbyterians.21

Conclusion

While the term “Calvinism” is tricky to define, it has stuck around long enough to be unavoidable. It is most commonly applied to the doctrine of divine predestination—which was explained from the Scriptures by Augustinian theologians and then most fully by Reformed theologians associated with John Calvin. Calvinism further distinguishes itself by applying concepts of divine sovereignty to church and social life, creating a diverse collection of theologians, pastors, and statesmen who seek to make all of life follow God’s word for his glory. They do this with the confidence that it is God himself who is at work in them. And they believe that he can and will fulfill all of his plans for their good.

Related articles

- The Definitive Guide to Christian Denominations

- What Is Reformed Theology? Its Roots, Core Beliefs, and Key Leaders

Resources referred to in the article

Calvin and the Reformed Tradition: On the Work of Christ and the Order of Salvation

Regular price: $39.99

Charles H. Spurgeon’s Autobiography, Compiled from His Diary, Letters, and Records, Vol. 1

Regular price: $9.99

Reformed Thought on Freedom: The Concept of Free Choice in Early Modern Reformed Theology

Regular price: $31.99

Divine Will and Human Choice: Freedom, Contingency, and Necessity in Early Modern Reformed Thought

Regular price: $44.99

Reformed study resources

- See Richard Muller, Calvin and the Reformed Tradition (Grand Rapids, IL: Baker Academic, 2012), 54–55; Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons 1910), 8:15.132.

- “Neither are the professors of the Gospel to be entitled by the names of such as have been famous instruments in the Church, as to be called Calvinists, Lutherans, &c.” William Perkins, A Golden Chaine (Cambridge: John Legat, 1600), 721–22.

- Robert L. Dabney, The Five Points of Calvinism (Harrisonburg, VA: Sprinkle Publications, 1992), 6.

- See Bruce Gordon, Zwingli: God’s Armed Prophet (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021), 6, 266–71, 274–75.

- See Gerald Bray, Documents of the English Reformation: 1526–1701, 3rd ed. (Cambridge: James Clarke & Co., 2019), 396–97.

- See especially Institutes, 3:21–24.

- Richard Muller notes that English opponents of Calvinism were using the term “Calvinist” as early as 1595; see Muller, Calvin and the Reformed Tradition, 55.

- Charles Spurgeon, C. H. Spurgeon’s Autobiography, Compiled from His Diary, Letters, and Records, by His Wife and His Private Secretary, 1834–1854 (Cincinnati; Chicago; St. Louis: Curts & Jennings, 1898), 1:167.

- B. B. Warfield, “Calvinism,” in Calvin and Augustine, ed. Samuel G. Craig (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1974), 291.

- Warfield, “Calvinism,” 292.

- Warfield, “Calvinism,” 288.

- See also the approach of D. G. Hart, Calvinism: A History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013).

- John Calvin, Commentary on 1 Cor 11:2; see also his comments on 1 Cor 11:3.

- Richard Hooker, The Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity, preface 2.8, in The Works of Richard Hooker, Vol. 1, ed. J. Keble (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1888), 139.

- The most famous of these was Vindiciae Contra Tyrannos: A Defense of Liberty Against Tyrants, by the pseudonymous author Junius Brutus.

- Many of Kuyper’s works have been translated into English for Lexham Press’s august Abraham Kuyper Collected Works in Public Theology series.

- Abraham Kuyper, Lectures on Calvinism (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1931), 17.

- George Herbert, “The Elixir” in The Temple.

- For a comprehensive discussion of this, see Willem J. Van Asselt, J. Martin Bac, and Roelf T. teVelde, eds., Reformed Thought on Freedom: The Concept of Free Choice in Early Modern Reformed Theology (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2010); Richard Muller, Divine Will and Human Choice: Freedom, Contingency, and Necessity in Early Modern Reformed Thought (Grand Rapid, MI: Baker Academic, 2017).

- Or the five tenets of Calvinism.

- For a discussion of this point see Muller, Calvin and the Reformed Tradition, 46–47, and Jonathan D. Moore, “English Hypothetical Universalism: John Preston and the Softening of Reformed Theology,” reviewed by Richard A Muller, Calvin Theological Journal, 43 (2008): 149–150.