October 31, 1517. It has become popular to see this date as the beginning of a decline: from Christendom to secularism, from community to individualism, from Catholicism to Protestantism, from one, holy, apostolic, catholic church to thousands of not-so-holy, not-so-apostolic, not-so-catholic churches.

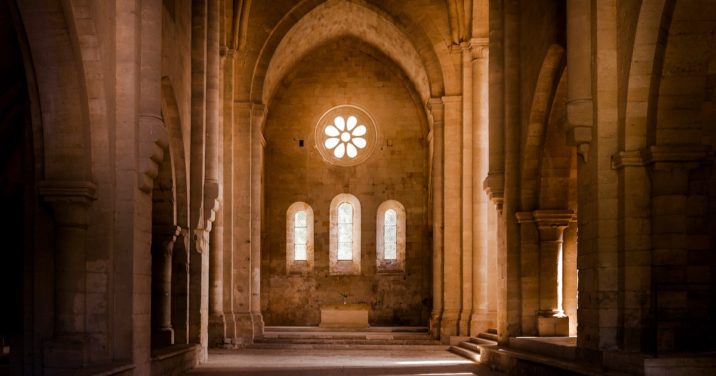

This is to ignore or to forget what happened on October 31, 1517, and why it happened. On that day, an unknown but annoyingly persistent Augustinian monk posted Ninety-Five Theses for discussion about the church’s current practices of forgiveness. He posted them to the door of the Castle Church of Wittenberg, and he sent them by post to his bishop and the archbishop of Mainz.

At that time, the church exchanged the forgiveness of sins for money. This raised three anxious questions:

- How can I know that my sins are forgiven?

- How can I know my standing before God who made heaven and earth?

- How can I know that what the pastor says is what God says?

These anxious questions required pastoral answers.

Pastoral answers require the logic of God’s Word. For Martin Luther, the logic of God’s Word is distilled in the catechism—that is, the Ten Commandments, the Apostles’ Creed, and the Lord’s Prayer. “Whatever all of Scripture holds,” Luther said, “it is simply expressed in these three.” To read the Bible by the catechism is to read the Bible by its own light. That’s the genius of Martin Luther and his Reformation insight. And—to the surprise of many Protestants—it’s an insight he learned from the Roman Catholic Church.

To read the Bible by the catechism is to read the Bible by its own light. That’s the genius of Martin Luther and his Reformation insight.

Luther’s rule of faith

Like any faithful medieval Catholic child, young Martin Luther learned the Ten Commandments, the Apostles’ Creed, and the Lord’s Prayer by heart before entering school. These three texts are the ABCs of the Christian faith and Bible reading. Just as it’s impossible to read and write without knowing the ABCs, it’s impossible to confess the Christian faith and read the Bible without the Ten Commandments, the Apostles’ Creed, and the Lord’s Prayer. Luther called these three texts of the catechism “the rule of faith.” They are the standard by which all teaching and preaching and living are tested.

Unfortunately, these three golden texts were presented as nothing more than ethics. At least, that was Luther’s assessment. “When I was twenty-one, I went to Mass three times a day. What kind of preaching did I hear? The kind that made a terror out of Christ and Moses’ Pentecost out of the Holy Spirit’s Pentecost. Yes, not so good. They stood on our own works.” Luther wasn’t against good works; what he was so upset about was the confusion of law and gospel. The gospel was presented as good works—just more stuff you need to do to make yourself good enough for God and his salvation. But that’s not the good news of the gospel! The good news of the gospel is that Jesus is a gift for us—no matter who we are or what we have done. He takes all our sin and gives us all his righteousness.

Luther spent his entire career preaching and teaching these texts, clearly and simply proclaiming the faith, hope, and love of the Bible. As he did this, he tested the teaching and preaching of the church against this rule of faith. He answered the anxious questions of his day according to the Ten Commandments, the Apostles’ Creed, and the Lord’s Prayer. This radically conservative idea was what got Luther into so much trouble.

Question 1: How can I know my sins are forgiven?

Luther’s Answer: Your sins are forgiven because Jesus took your sin and gave you his life by his death and resurrection. Your sins aren’t forgiven because of gold and silver, but because of the blood of Jesus (1 Pet 1:18–19; Acts 20:28). Or as we say in the Apostles’ Creed, “I believe in the forgiveness of sins,” and in the Lord’s Prayer, “Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us.”

Question 2: How can I know my standing before God who made heaven and earth?

Luther’s Answer: By the word God has spoken. For example, “For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Savior, who is Christ the Lord” (Luke 2:11). But Luther also believed that the whole catechism was composed for us by God: “God himself gave the Ten Commandments. Christ himself prescribed the form of the Lord’s Prayer. The Holy Spirit composed the Creed most exactly.” The Ten Commandments tell you that the Lord is your God. The Apostles’ Creed tells you that the God who created heaven and earth died for you—for your forgiveness, salvation, and life. And the Lord’s Prayer tells you that you can speak with the creator of heaven and earth the way a small child speaks with her dear father.

Question 3: How can I know that what the pastor says is what God says?

Luther’s Answer: If it fits with the Ten Commandments, the Apostles’ Creed, and the Lord’s Prayer, you should accept what your pastor says as what God says. If it does not, it’s not God’s word, and it should be rejected.

In the end, this conservatism proved too radical for the Roman Catholic Church. Luther was released from his monastic vows (1518), excommunicated by the pope (1521), and, to add insult to injury, declared an imperial outlaw (1521).

Returning to the ancient art of catechesis

Those anxious questions of Luther’s day are still being asked today. But are pastors and everyday Christians equipped to answer them? For many, the answer is the same as it was in Luther’s day: no. Sadly, too many Protestants have let go of the ancient art of catechesis, replacing it with the latest trends in church growth, contemporary music, biblical studies, or personality tests. The heirs of the Protestant Reformation need to return to the deposit Martin Luther received from the Roman Catholic Church and which the Roman Catholic Church had in turn received from the Bible: the Ten Commandments, the Apostles’ Creed, and the Lord’s Prayer. These were the ABCs that made Luther’s pastoral protest legible, and the grammar that made his pastoral protest sensible.

This ancient catechism opens up the Bible and is a salve to the heart and conscience of the Christian. It’s simple, concrete, and personal, but also inexhaustible—you’ll never run out of the faith, hope, and love that it teaches. As Luther said, “These are the three greatest sermons!”

***

Read more of Dr. Hains’s insights on Martin Luther in his new book, Martin Luther and the Rule of Faith: Reading God’s Word for God’s People. In the book, he goes deeper into how Luther’s rule of faith impacted his reading of Scripture and guided his biblical interpretation. Pick up the book today to expand your view of Luther and bring clarity to your own reading of God’s Word.

For further reading

Martin Luther and the Rule of Faith: Reading God’s Word for God’s People (New Explorations in Theology)

Regular price: $31.99

Disputation of Doctor Martin Luther on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences (95 Theses)

Regular price: $2.49