This article was originally three separate articles that ran in Bible Study Magazine in 2022. We’ve combined them all in one location for easy access. You can use the table of contents below to navigate the content.

Table of contents

Part 1: Abram’s Narrative in the Story of Genesis

When humanity conspired against God in the plain of Shinar (Gen11:4), they sought for themselves a name, a nation (i.e., a city), and to be a blessing to the whole world (i.e., a tower with its top in the heavens). God stooped down and wrecked their plans, like a parent cleaning up the tinker toy towers of unruly children. The problem, however, was not with the rewards they sought, but with the manner in which they sought them. Such names, cities, and rewards cannot be grasped for oneself, in opposition to God; they must be received from him through faith. The epic tale of Abraham will show us how this works.

Here we’ll begin to work through the story of Abraham (Gen 11:27–25:18), to see both God’s great promises and Abraham’s faith. Along the way, we’ll strengthen our skills at reading and studying the Bible’s narratives—especially by learning how to mine for the story’s meaning by tracing its plot arc.

Week 1: Promises for the undeserving

The opening scenes of the story of Abram (when that’s still his name) are not the most action-packed, but they provide crucial information we must keep in mind as we progress. Let’s take careful note of this information so we can call upon it as needed in later chapters.

Read Genesis 11:27–12:3 a few times.

In verse 27, the formula “these are the generations of” signals a new section of Genesis (see the overview of Genesis in BSM 14.2), which is about the progeny of Terah. The first thing we’re told about Terah is that he fathered three sons. Who else, earlier in Genesis, fathered three sons, and what does the connection suggest? See Study Note 🅐 if you’d like some help.

Terah outlives one of his sons in his homeland. Where is that homeland? Search online or use a Bible atlas to find this location. What else took place in this very same region, earlier in Genesis? See Study Note 🅑.

Draw Terah’s family tree; it will come in handy later when these names reappear. What is the primary thing we’re told about Abram’s wife Sarai? Whose idea was it to relocate to Canaan? Why did they not make it there? What does Joshua 24:2 say that Terah, Abram, and their family were doing at this time?

Now for perhaps the most important information: Observe 12:1–3 carefully! What does the Lord want Abram to do? Where does the Lord want Abram to go? What will the Lord do for Abram there? (Note: If you are thinking about Canaan, you are allowing your familiarity with the end of the story to prevent you from observing it closely enough. God does not yet tell him where to go, does he?)

God promises Abram three things, which will drive the plot for the next 13 chapters. Each episode in Abram’s narrative focuses on one or more of these promises, so let’s make sure we identify them clearly. What are the three promises, and how do they relate to the three things sought by the builders at Babel? See Note 🅒. On a piece of paper, make three columns. Label those columns with the three promises. Over the next few days, and before moving on in our study, read the rest of Abram’s story, placing each episode in the column that matches the promise under consideration in that episode.

Week 2: Not knowing where he was going

The first three words of Genesis 12:4 astonish: “So Abram went.” Remember, God hasn’t given him a map or particular destination yet. All he’s said is, “Go away from your country and family.” Hebrews 11:8 underscores the point: “He went out, not knowing where he was going.” Genesis 12:1 simply says that God will show him the land of promise once he gets there. What sort of picture does this paint of the character of Abram?

Read Genesis 12:4–20 a few times.

Where does Abram go? Why do you think he goes there? (Review Genesis 11:31.) What does the Lord do once he arrives? Which of the three promises are being addressed in Genenis 12:4–9? How is that promise advanced? (In other words, how does Abram get a little closer to receiving what was promised?) See Note 🅓 if you need help.

In Genesis 12:10–20, which of the three promises is in view? Resist the temptation to read this story as merely a morality tale about truth and deception. The narrative’s drama resides in the presentation of that which threatens the fulfillment of Yahweh’s promises. Which promise is under threat here? What is that threat? How is the threat resolved? Who is responsible for that resolution? See Note 🅔.

How deserving is Abram of these promises? How important is it to the Lord that Abram be deserving? What seems to be the Lord’s chief concern instead? Why has the Spirit-inspired narrator placed this episode immediately after the scene of Abram’s demonstration of astonishing faith? What does this tell us about God’s promises to us?

Week 3: They could not dwell together

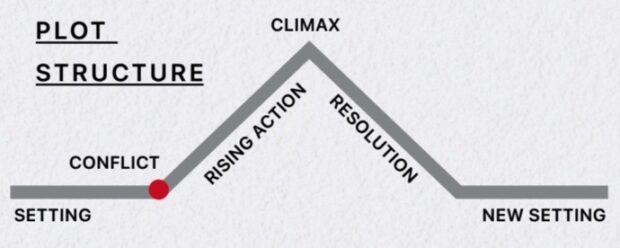

This week, we will begin practicing the skill of observing plot structure. You may remember terms such as conflict, climax, and resolution from elementary school, and the time has come to dust off these concepts. Plot structure is one of the most handy tools for understanding a narrative text, and those who learn to recognize plot structure are more likely to grasp what is important in the story.

Before we dive in, let me explain what I mean by plot structure. Narratives tend to have a basic shape with six elements:

Setting: The characters, locations, and situation are established.

Conflict: The tension that will propel the story is introduced as an opposition between two parties (man vs. man, man vs. God, man vs. nature, man vs. himself, etc.).

Rising Action: The tension ebbs and flows, or additional tension is layered on, to increase suspense.

Climax: The conflict is finally settled, typically through some sort of reversal.

Resolution: The ends are tied up to release the tension (sometimes called the denouement).

New Setting: The characters (and often the readers) find themselves in a new situation or circumstance because of the conflict’s reversal.

The most important element for us to notice is the climax, because that is where we’ll normally find the narrative’s point or main idea. But in order to find the climax, we must first be clear on what the conflict is (what the precise source of narrative tension is). After we locate the introduction of the conflict, we’ll be able to perceive the reversal of that conflict at the point of climax. The remaining elements of plot structure largely fill in the gaps.

This week, I will model this process for you with Genesis 13. Please follow along with your Bible and notebook in hand so you can replicate the steps. In the remaining weeks of this study, I will not be as forthcoming but will prepare you to do more of the work yourself.

Read Genesis 13 a few times.

Step 1: Identify the precise point where the text introduces conflict. You will find it by figuring out where the narrative creates tension or begins to feel as though something could go wrong.

In Genesis 13, no tension is present until verse 6. Before that, Abram is simply moving around, having lots of stuff, and calling once more on the name of Yahweh. But in verse 6, “The land could not support both of them [Abram and Lot] dwelling together.”

Step 2: Label everything prior to the introduction of the conflict as Setting.

In Genesis 13, verses 1–5 serve as setting, an extended setup for the plot to unfold, beginning with verse 6.

Step 3: Figure out the precise nature of the conflict. In other words, who or what is in conflict with whom or what? Or what is the chief question raised by the plot conflict?

In Genesis 13, the conflict poses a threat to the Lord’s promise that Abram would sire a great nation that holds this land (promise vs. reality). The chief question is: If this land can’t even hold two families, how will it ever hold an entire nation?

Step 4: Find the story’s climax, which will be the precise place near the end where the conflict is solved or reversed in some way.

In Genesis 13, the climax comes in verses 15–17 when Yahweh reiterates the promise to Abram. Though his offspring will be as numerous as the dust of the earth, this very land, all that Abram can see, will still be sufficient to hold them.

Step 5: Label everything between the conflict and the climax as Rising Action. Trace the steps where the conflict deepens or advances.

In Genesis 13, verse 7 tells us the triggering event for the conflict, which is the strife between Abram’s herdsmen and Lot’s herdsmen. So there is more going on than simply whether the land is big enough. The action rises further with the note (v. 7) that two entire nations are also presently inhabiting the land along with the two families of Abram and Lot—explaining why it feels a bit overcrowded.

Then (v. 8), Abram describes the issue first as being “between you and me” and only secondly as “between your herdsmen and my herdsmen,” suggesting that the main problem here might actually be Lot’s. Perhaps the statement in verse 6 that “the land could not support both of them” was not truly the narrator’s assessment but more likely the assessment of Lot’s character?

Limited space prevents me from covering every detail. So I will let you continue to work through the rising action for yourself. The goal is simply to let the story speak for itself, allowing the original, stated tension to wax and wane at each new development.

Step 6: Observe how the new setting, post-climax, differs from the initial setting at the story’s beginning.

In Genesis 13:18, we now have Abram dwelling near Mamre’s oaks and worshiping Yahweh like before—only without Lot (vv. 4–5).

Step 7: Label any material between the climax and the new setting as esolution. These details may paint a picture of what it looks like to live in light of the story’s climax.

In Genesis 13, the resolution is not extensive but simply describes Abram moving his tent to a new location, getting a fresh start without his nephew.

Step 8: Figure out the story’s main point, which is closely connected to the climax and/or resolution.

The main idea of Genesis 13 appears to be that God will keep his promise to Abram to give him a great nation within this land—but apart from Lot, who will not be his heir. The promise will not be realized through Lot but through another. Lot’s exclusion from the promise may have something to do with his preference for the presumed paradise of worldly wickedness (Gen 13:10, 13). We also learn that Yahweh’s promises to Abram will involve the land he can see (v. 15) but not the heir he can see. Something more than sight will be required of him.

If this process of tracing plot structure appears tedious, let me assure you that there is a mysterious glory to it. Hone your ability to trace the plot structure, and you may be surprised by how it unlocks the meaning of most of the Bible’s narratives for you. The crucial steps are 1, 3, 4, and 8, but everything is there to help you arrive at the story’s main point.

Week 4: Who is Abram’s King?

Read Genesis 14 a few times.

This week you get to work on the plot structure yourself, but here is some help. The setting in this story is quite extensive. Keep in mind that this story is part of Abram’s story, so the chief conflict is that which involves him or the Lord’s promises to him. Neither the history lesson nor the many battles recounted at the beginning are the main source of plot conflict.

With that said, follow the steps I outlined last week. Especially: Where is the conflict introduced? What is the nature of that conflict? Where is it solved or reversed? What is the main idea?

Now dig a little deeper. The extensive setting is there for a reason. Observe which words are repeated the most in this chapter. One word is repeated so frequently and obviously that it, ironically, can be easy to miss (see Note 🅕). How does that extensively repeated idea shape the story’s plot? See Note 🅖.

What does this story’s main idea tell you about Abram’s perspective toward the Lord and his promises? How should that shape your perspective toward the Lord and his promises?

Week 5: Faith counted as righteousness

Keep building on the work you’ve done so far! As you move to the next episode in Abram’s story, keep in mind all that has come before.

Read Genesis 15 a few times.

Where does the tension begin? Which of God’s promises from 12:2 is under consideration? Where, near the end of the chapter, is the tension fully resolved? What new tension is embedded within that resolution and new setting? See Note 🅗 if you need help.

Trace out the phases of rising action between the conflict and climax. How does Yahweh respond to Abram’s inner conflict? How does Abram respond to Yahweh’s assurance? Why do they continue back and forth in dialogue and response?

Genesis 15:6 is quoted three times in the New Testament (Rom 4:3; Gal 3:6; Jas 2:23). Read each of those chapters and consider: What argument is Paul or James making? How does the context (the full story) of Genesis 15 support his argument? How is Abram’s faith a model for ours?

Week 6: A God who sees

I won’t provide any answers this week; I’m confident you can do it yourself. I encourage you to take note of seeing and hearing in this week’s text.

Read Genesis 16 a few times.

List the six elements of the plot structure, with verse references for this story. What is the nature of the conflict? Which of Yahweh’s promises are under consideration? What is the nature of the climax? What is the story’s main idea? What does that main idea teach us about trusting God’s promises? How can we better see and hear the Lord Jesus?

May you delight anew in your God who sees and hears all you’re going through (Gen 16:13), and who is himself your shield and very great reward (15:1).

Study notes

🅐 Adam had three sons (Cain, Abel, Seth), and so did Noah (Shem, Ham, Japheth). Both Adam and Noah were new humans at the start (or restart) of God’s creation. The description of Terah with his three sons suggests that the narrator wishes us to see another cycle of new creation and new humanity in the family of Terah.

🅑 “Chaldeans” (Gen 11:28) is the Bible’s word for the people who lived in the region of Babylon, which is the same place where the tower of Babel was built (in Hebrew, Babel = Babylon). Therefore, in the very place where God scattered humanity, he also selected one family to advance his new creation.

🅒 In Genesis 12:2, the Lord promises Abram a great nation, a great name, and an infectious blessing. In Genesis 11:4, the builders wanted a city (to hold a great nation), a great name, and a tower (that would have influence over the world). God took all three things from the “Babel-onians” and gave them to Abram, an idolator (Joshua 24:2), for free.

🅓 In Genesis 12:4–9, the main promise in view is that of the great nation, which is now closely connected to receiving the land. In verse 7, Abram gets closer to receiving the promise in that the Lord now tells him that this (Canaan) is it! Now he knows the right location where his nation—his offspring—will take up residence.

🅔 Regardless of which of the three promises you observe being threatened, you are correct. First, when famine hits the land (v. 10), it threatens the viability of this land for Abram’s coming great nation. Second, when Pharaoh abducts Sarai for his harem (v. 15), it threatens the promise of Abram’s great name. Third, when Pharaoh treats Abram well for her sake (v. 16), it seems to question the promise that Abram would be the source of the world’s blessing. This brief story brilliantly weaves all three promises together by bringing each of them under some sort of threat. But just when everything seems about to unravel, Yahweh afflicts Pharaoh and his house with great plagues (v. 17). The Lord will not allow his promises to go unfulfilled.

🅕 King is repeated 28 times in the English Standard Version. Even more if you count Melchizedek’s name, which means “king of righteousness.”

🅖 The plot conflict consists in the kings’ claim to Lot and his possessions. Though Lot has moved away, Abram still holds himself responsible for Lot’s well-being. The question is: Which king has claim to Lot (and thereby to portions of Abram’s household)? The climax is therefore not simply when Abram rescues Lot, but when he gives a tenth of the spoil to Melchizedek in verse 20, acknowledging Melchizedek’s kingship over him. Really, he’s acknowledging that God Most High, who is Mechizedek’s king, is Abram’s king as well.

🅗 Conflict in verses 2–3: Abram has no “reward” of children but only a household servant as his heir. This affects the promises of a great name and great nation. The climax comes in verse 18, where the covenant ceremony is complete, guaranteeing the promise of this land for Abram’s own offspring. The new setting, however, prophesies an ominous future for those offspring.

Scripture quotations are from the English Standard Version.

***

This article was originally published in the May/June 2022 issue of Bible Study Magazine. Slight adjustments, such as title and subheadings, may be the addition of an editor.

Part 2: The Nature & Benefits of Faith in the Promises of God

While Abram was an idolator in Ur of the Chaldeans (Josh 24:2–3), God appeared to him and made three staggering promises (Gen 12:1–3).

- I will make you into a great nation.

- I will make your name great.

- I will make you the source of blessing for the whole world.

Abram’s kinsmen had tried to seize these very three things for themselves (Gen 11:2–4), but God elected to give the promises to this one man for free. All he had to do was receive them and live as though he believed they would come true.

In part one of the study (above), we explored the first portion of Abram’s narrative in the book of Genesis. We learned along with him that becoming a great nation would involve inheriting the land of Canaan. Acquiring a great name would involve securing an heir from his own body. And blessing the world means fighting evil, giving generously, and not hiding behind his wife.

In part two, our study will focus on what Abram’s story teaches us about the nature and benefits of faith in the promises of God. We pick up the action right after the birth of Abram’s own son, Ishmael (Gen 16:15–16). It was a rough ride to get here, but Abram’s finally got his heir.

Week 1: My Covenant in Your Flesh

The epic story of Abraham is filled with intense drama—drama that is nonetheless easy to miss because the Hebrew narrative style is so straightforwardly, brilliantly simple. For example, if my last sentence in the previous paragraph tripped you up, you may be impaired by your familiarity with the story.

If you thought, “Wait a minute… Ishmael’s not his heir,” you might benefit from re-reading the whole story, from Genesis 11:27 through the end of Genesis 16, while putting yourself in Abram’s shoes. He relocates to Canaan with his family (12:4–5). His nephew disinherits himself (13:11), though Abram still fights to protect him (14:15–16). Abram believes his estate will pass to his homeborn servant (15:2). God assures him he’ll have a son of his own (15:4). Eventually, Abram’s own son is born (16:15–16).

So as you come to chapter 17, set aside (for now) where you know the story is heading. Read it with a view toward how Abram would have experienced these events. Catch the drama. The dearly-held expectations. The length of time that passes with tremendous patience.

From 16:16 to 17:1, years have passed. Thirteen years in which Abram (which means “exalted father,” by the way) has been raising his son, his own son, presumably teaching him the ways of the Lord. Teaching his son about the three great promises for their family. About the glorious future for their people and the nations of the world. In that setting …

Read Genesis 17 a few times.

The clauses “God said to Abraham” (or “God said to him”) serve as narrative markers that divide God’s speech into three sections. Who is the main subject of each section? What does God say each of those subjects will do or should do? Try answering these questions yourself first, but then see Note [A] at the end of this study if you’d like some help.

Over the course of these three sections, which promises or instructions look back to the past, connecting Abraham to Noah and Adam before him? Which promises or instructions shock him in the present, drastically altering his view of the world? Which promises or instructions assure him for the future?

Why do you think Abraham advocates for the status of Ishmael (v.18)? How would God’s response assure him?

Look again at how Abraham responds to God’s speeches (verses 23–27). What picture does this paint of Abraham’s trust in God?

Now to conclude this week’s study, take a look at Hebrews 11:11–16 and Romans 4. What do these apostolic reflections on the faith of Abraham suggest regarding the Christian’s faith in Jesus Christ? What hinders you from trusting the Lord Jesus Christ amid your darkest circumstances?

Week 2: I Have Chosen Him

God has appeared to Abraham, expanding his promises by assuring Abraham that Ishmael will not be his heir. Instead, Sarah herself will conceive and bear a son “at this time next year” (17:21). The following scene in chapter 18 takes place at nearly the same time, since the Lord repeats that Sarah’s son will be born “about this time next year” (Gen 18:14). Abraham laughed with delight at God’s promise (Gen 17:17). How will Sarah now respond?

Read Genesis 18 a few times.

When Abraham sees three visitors and welcomes them to his home, whom is he entertaining unawares? See Note [B]. At what point in the story does the narrator suggest Abraham realizes who exactly he is speaking with? How do you know?

In the opening paragraph, what sort of a host is Abraham? (Find a Bible dictionary, such as the Lexham Bible Dictionary, to explain the units of measurement to help you figure out how much food is prepared.) How have his life experiences so far shaped him to be so lavish in generosity?

What is the purpose of the visit from the three travelers? Which of the three promises is in view? The Lord already delivered this news to Abraham in the previous chapter; why does he visit over supper to deliver it again? What is the response? What is significant about Sarah’s laughter, to make the Lord draw attention to it in verses 13–15?

Note: Verse 12 is the only time in the biblical record that Sarah refers to Abraham as her lord. Why do you think Peter picks up on this moment in her life to set her as an example for fearless and holy women (1 Peter 3:1–6)?

Where are the men standing for the chapter’s final conversation? Take note of this location, as it will become important in next week’s study. What do the Lord’s monologues in verses 17–21 communicate about his relationship with Abraham? How did their relationship grow to become like this?

In the bargaining at the chapter’s close, what is the main thing driving Abraham to speak up? What is at stake regarding the character of God? Notice how much back-and-forth, cyclic detail the narrator describes. Why do you think he describes the negotiations with such vivid particulars? What kind of picture does this paint of Abraham, his faith in God, and God’s accessibility to those who trust him?

If you feel like the plot hasn’t really climaxed or resolved yet, you’re well in tune with it. Chapters 18 and 19 fit closely enough together that they ought to be considered as one long unit. But sometimes it’s helpful to divide such a lengthy text. So don’t worry about the lack of resolution, and bring your questions back next week into your study of the next chapter.

Week 3: Escape to the Hills!

In chapter 18, Abraham entertained the Lord and two of his angels, serving them a lavish meal. There was a conversation about offspring at the entrance of the residence. Abraham’s guest then revealed what he was about to do, and Abraham bargained with him in favor of a different outcome.

Prepare yourself for some deja vu, for a similar sequence of events is about to be repeated.

Read Genesis 19 a few times.

Make a list of comparisons and contrasts between this chapter and chapter 18. In particular, consider my summary in the opening paragraph of this week’s study, and take note of all the similarities and differences in Lot’s entertaining of his guests. What do these similarities and differences suggest about Lot’s character? As you make your list and reflect on the narrator’s characterization of Abraham and Lot, don’t forget that the Apostle Peter considered Lot to be a righteous man, distressed by everything going on around him (2 Peter 2:6–8).

At the end of chapter 18, the Lord promised not to destroy Sodom and Gomorrah if his angels found only 10 righteous people there. Upon inspection, how many righteous people did they find? The Lord still destroyed the cities, but what is the answer to Abraham’s chief question (“Will you indeed sweep away the righteous with the wicked?” [18:23])? What if there is only one who is righteous? Will the Lord sweep him away with the wicked?

Last week, I asked you to take note of where Abraham had his final conversation with the Lord. Now: Where do the angels want Lot to go in order to escape the coming judgment (v.17)? What is the significance of going there (vv.27–28)? What is Lot’s counteroffer (vv.19–20)? What has Lot learned since the last time he made a similar choice (Gen 13:10–13)? How does it work out for him the second time around (vv.30–38)? See Note [C].

What does this chapter teach about the judgment of God? What does it teach about the nature and benefits of faith in God’s promises? What does it teach us about attaching ourselves to the man of faith through whom God will bless the world? What does all of this teach about the Lord Jesus and your faith in him?

Week 4: He is a Prophet

This week, more deja vu. When narratives recount similar incidents, there is a reason for this repetition beyond simply communicating that “this thing happened again.” So as you take a look at Genesis 20 this week, you’ll want to keep a close eye on chapter 12 so you can distinguish between the episodes. Our goal is to understand why the narrator includes both incidents and what the repetition communicates about Abraham’s faith (or struggle with faith) in God’s promises.

Read Genesis 20 a few times. Then go back and read Genesis 12:10–20 a few times.

Make yourself a list of all the similarities and differences you can find between the two stories. Here are some specific questions to help you distinguish them:

- How is the setting similar or different? What causes Abraham to relocate his household in each story?

- What instigates the plot conflict in each story?

- What is similar or different about Abraham’s role in each story? How is his rationale for his actions similar or different in each story? How is he described in each story?

- What is similar or different about Sarah’s role in each story?

- What is similar or different about the king who seizes Sarah for his harem in each story?

- What is similar or different about God’s role in each story? How does his judgment on the king fit the crime?

- What is similar or different about the resolution of each story? What offer does each king make to Abraham after learning about the deception? What does Abraham come away with?

- Which of God’s three promises to Abraham is at stake in each story? How does the story’s resolution protect or advance those promises?

Now, in light of all those similarities and differences, what appears to be the particular focus of this second incident in chapter 20? While we may be inclined to focus our attention on where to lay the blame for what happens in this chapter, the flow of the larger story of Abraham should have trained us by now to ask a more important question: How does this episode further the promises God has made to Abraham? What sort of God is he when everything becomes a big, tangled mess?

Week 5: The Lord Did as He had Promised

Since chapter 16, the Abraham story has given particular attention to the promise that Abraham’s great name would be carried through the birth of a son. Not Ishmael. Not Lot. But one born by Sarah herself. So now we reach something of a climax in this middle section of the larger epic.

Read Genesis 21:1–21 a few times.

Review your notes from chapters 16 to 20 and write down everything God has said or promised that finds fulfillment in this story. This is not my own idea, but is the very thing the narrator wishes you to do: “The Lord visited Sarah as he had said, and the Lord did to Sarah as he had promised” (Gen 22:1).

Our God is a promise-keeping God. He is a God who keeps his word. This story paints this picture with vivid strokes, so let’s not miss that point. How can this story encourage you when you struggle to believe that God will do as he has said? How does this story paint a picture of Abraham’s faith? How does it paint a picture of Sarah’s faith?

In chapter 16, God told Hagar to return to Sarah after having run away from her. Why does he now support the plan to send Hagar and her son away? What has changed to make the separation a good idea? How does God still keep his word to both Hagar (see 16:10–12) and Abraham (see 17:20)?

What is the triggering event to cause the need for separation in this chapter? What is going on there? It may help to know that the name Isaac means “he laughs.” Isaac’s name has been the subject of wordplay over the course of the last few chapters (see 17:17; 18:12–15; 19:14 [“jesting” is the same Hebrew word]; and 21:6). In addition, did you observe that Abraham’s first son is never called by his name in chapter 21? What do all these things suggest about what is going on to trigger the separation? See Note [D] if you could use some help.

What do all of these things teach us about the Lord and his promises? What does the story teach about the nature of faith in God’s promises? What promises has God made for those who set their faith in his Son, Jesus Christ? How does Abraham’s story assure you to trust that God will do what he said he will do?

Study Notes

🅐 Part 1 (verses 1–8) is about God: “I am God Almighty.” It describes all the things God himself will do for Abram: make a covenant, multiply him, make him a father of nations to live up to his new name, make him fruitful, etc. Part 2 (verses 9–14) is about Abraham: “As for you.” Abraham must keep God’s covenant by circumcising every male in his household. Part 3 (verses 15–21) is about Sarah: “As for Sarai your wife.” She is to give birth to her own son, named Isaac, who will carry forward God’s everlasting covenant.

🅑 Make sure to check 18:1, 18:22, and 19:1 for the precise identities of the three visitors.

🅒 The angels want Lot to escape to the hills, where Abraham is living. Presumably, they are encouraging Lot to return to Abraham’s household. Lot refuses, perhaps still wishing to keep his distance from his uncle. Instead he asks for the Lord to spare the littlest of the towns on the plain. But Lot doesn’t stay there long. Instead of going to live on the mountain with Uncle Abraham, he ends up living in the mountain with his daughters—whose lives now look more like those of Sodom than those of the faith of Abraham. Lot and his family could not keep Sodom going physically or economically, but they could continue its legacy in their hearts and home life. Such are the risks of refusing association with the one through whom God has chosen to bless the world.

🅓 Though many translations use words like “mocking” in 21:9 to make Ishmael appear sinister, the constant wordplay over many chapters strongly suggests that Ishmael is simply trying to out-Isaac Isaac as the son of promise comes of age. In other words, to be extremely literal, 21:9 says that Sarah sees the unnamed son of Hagar Isaacking. Perhaps she thinks, “Oh no he doesn’t. There’s only one Isaac. There’s only one son of the promise. The son of the slave woman must go, lest there be any doubt or confusion at all as to who the true heir is.” And lest you think I may be reading too much into the story here, is this not precisely how the Apostle Paul reads this story in Galatians 4:21–31.

***

This article was originally published in the July/August 2022 issue of Bible Study Magazine. Slight adjustments, such as title and subheadings, may be the addition of an editor.

Related resources

Part 3: Abraham’s Faith & Our Own

Faith is one of those fancy Christian words we can find ourselves using a lot without truly understanding what it means. To many in American culture, “faith” is the opposite of reason and is best represented by a blindfold or reckless leap. For many churchgoers, “faith” is a personal and private matter, perhaps something to be either kept or shared. On college campuses and in public spaces, “faith” is simply a nickname for a religion; thus a “faith” can be a set of doctrines, a cultural spirituality, or a set of heartfelt rituals.

In the previous sections of this Bible study (part one and part two above), we worked our way through the Abraham narrative in Genesis, culminating in the birth of Isaac, the son of promise, early in chapter 21. We have considered Abraham’s faith in God’s three promises (Gen 12:1–3), which shape each episode of this brilliant epic.

- Abraham will become a great nation that inherits the land of Canaan.

- Abraham will receive a great name through his promised son.

- Abraham will become the source of blessing to all nations.

As we now conclude our study of Abraham’s story, we must consider not only Abraham’s faith but also our own. If “those who are of faith are blessed along with Abraham, the man of faith” (Gal 3:9),1 if those of faith are the true sons of Abraham (Gal 3:7), and if he is the father of those who are not merely circumcised but who also walk in his footsteps of faith (Rom 4:12), then it seems important we get this “faith” right. Therefore, this third installment of our study of Abraham will direct our attention to a crucial step in our Bible study process: application.

The Practice of Application

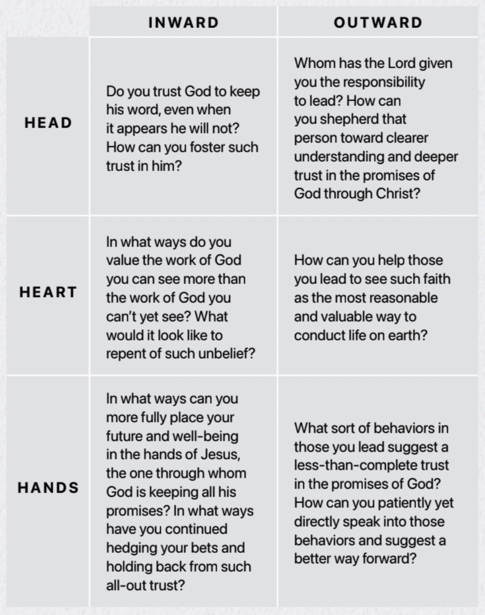

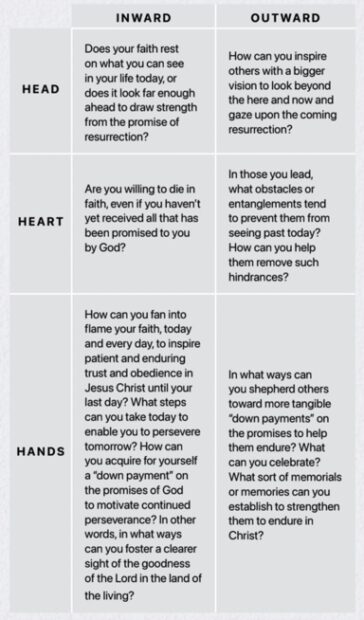

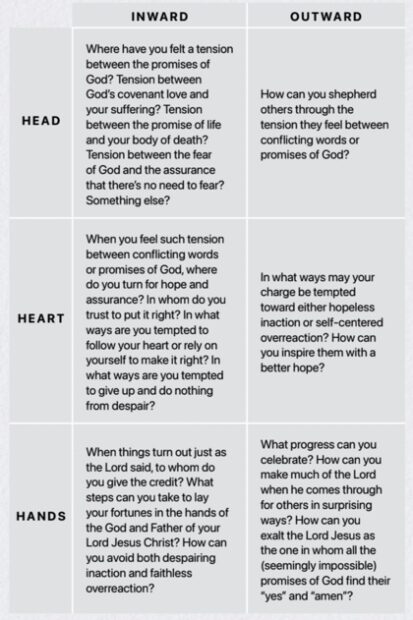

Before we dive into our text, let me describe a model for Bible application. We can apply the Bible in two directions:

- Inward application answers the question: How can I change? This fulfills the Great Commandments to love God and others (Matt 22:37–40).

- Outward application answers the question: How can I help and encourage others to change? This fulfills the Great Commission to make disciples (Matt 28:18–20).

We can also apply the Bible in three spheres:

- Head application addresses what we ought to know, think, or believe (or avoid thinking or believing).

- Heart application addresses what we ought to esteem, love, or value (or avoid esteeming, loving, or valuing).

- Hands application addresses what we ought to speak or do (or avoid speaking or doing).

Together, the two directions and the three spheres form a matrix of six potential areas to apply the Bible.

When it comes time to apply the main point of our passage, we can consider these six areas for potential application. You don’t have to fill in all six boxes every time you apply the Bible. But you should aim to cover all six boxes over time.

If it feels like you always come away from your Bible study with the same set of applications, perhaps you have gotten stuck thinking about the same box or two every time. In that case, this matrix can help you stretch your application muscles and nurture more fruitful change.

I’ll use the terminology from this model for the remainder of our study. Each week, I will give a little help with observation (O) and interpretation (I), but greater attention will be dedicated to practicing application. If you get stuck with the O or I, the last section (“Study Notes,” below) will help you along.

Week 1: Covenant at Beersheba (Genesis 21:22–34)

Which of the three promises to Abraham is primarily in view?

What is similar and different about the way Abraham and Abimelech treat each other? How do these comparisons drive the plot conflict?

What is similar and different about the way Abimelech (Gen 20:15, 21:32) and Pharaoh (Gen 12:19–20) treated Abraham?

What role does Abimelech’s ethnicity play in the story, and in Israel’s future?

What is the climax and main point of the story?

Application Questions

Inward: What is your perspective toward those who belong to the enemies of your people? Do you hold out any hope of peace or salvation for them? How have you seen the gospel cross racial, ethnic, or social lines in your community? What would it look like for you to exalt Jesus Christ as the savior of the whole world?

Outward: How can you make him more evident and available to others around you so they may join in the riches of the new covenant? How can you be an agent of God’s blessing to the world? What opportunities do you have to bring people together, to heal rifts, and to motivate others to trust in the good news of salvation by grace?

Week 2: By Myself I Have Sworn (Genesis 22)

What is the conflict? Which promise is under consideration? How does the promise itself create the conflict that drives the narrative forward? Where is the plot’s climax? Note: The climax is not necessarily the emotional or theological high point, but the point where the conflict is resolved or reversed.

In light of the promise under consideration, what role do the last few verses play? Why does the narrator choose now to tell us how many sons Abraham’s brother has? What is the story’s main point?

Application Questions

Week 3: These All Died in Faith (Genesis 23)

What is the plot conflict, and where is it introduced? Hint: While Sarah’s death is tragic, it does not drive this story’s plot. Most of the story is taken up with another matter altogether, for which Abraham’s loss of his wife provides the setting.

Which promise is under consideration? Where is the conflict solved or reversed in a climax? What is the main point?

Application Questions

Week 4: Do Not Take My Son Back There! (Genesis 24)

We come to another story that may be familiar. Once again, try to set aside your familiarity in order to observe the story closely.

In light of the larger narrative of God’s promises to Abraham, which promises are under consideration in this story? In verses 3–8, which two promises are clearly on Abraham’s mind? And which of the two is especially under threat?

As the conflict deepens through the rest of the story, who is the chief actor? How do you know? What does this tell us about how the conflict will be resolved?

Where is the climax? What is the main point?

Application Questions

Week 5: After the Death of Abraham (Genesis 25:1–18)

This week, you get to conclude the Abraham epic with your own study of the text. With many weeks to practice the skills, you are now ready to try this at home. Though this week’s passage (Genesis 25:1–18) may seem like a random collection of facts and names, your job is to figure out how it provides a fitting conclusion to the larger narrative of Abraham’s faith in God’s promises to him.

A template is provided for you below to assist your plot analysis and application. Allow this brilliant story to drive you to worship the very God who kept all his promises to Abraham through the Lord Jesus Christ.

The God of Abrah’m praise, Who reigns enthroned above;

Ancient of everlasting days, And God of Love:

Jehovah, Great I Am! By earth and heav’n confessed;

I bow and bless the sacred Name, Forever bless’d —Thomas Olivers

- Conflict:

- Promise under consideration:

- Climax:

- Main point:

Application

Study Notes

Genesis 21:22–34

Conflict: Verse 23: Abimelech vs. Abraham. Abimelech wants Abraham to treat him well, but will Abimelech reciprocate?

Promise under consideration: Those who bless Abraham will be blessed.

Climax: Verse 32: Abimelech and Abraham make a covenant; Abimelech returns home, leaving Abraham in peace to enjoy the well he dug.

Main point: When pagans, from recognition of the true God’s presence with Abraham, bless him, they, too, may come under the blessings of God’s covenant promises.

Notes: This episode makes little sense apart from the larger context of the three promises to Abraham (especially the promise of becoming a blessing to all nations). Knowing that God is with Abraham (v.22), Abimelech treats Abraham well, blessing him and wishing to live at peace with him. Like Pharaoh in chapter 12, Abimelech was lied to about Sarah’s relation to Abraham (20:1–2).

But unlike Pharaoh, Abimelech did not kick Abraham out of his country (12:19–20) but invited him to stay and retain ownership of his well. Abimelech the Philistine (ancestor to the future enemies of Israel) blesses Abraham and experiences in return the blessing of Yahweh for all nations through Abraham. Though the fulness of Jesus Christ’s salvation for the entire world had not yet been revealed, this story foreshadows the blessings of God’s covenant for all the nations of the world through faith in Jesus, the better Abraham.

Genesis 22

Conflict: Verse 2: God vs. his own promise. Will God give Abraham a great name through his son Isaac or not?

Promise under consideration: Abraham will receive a great name, through his and Sarah’s own son, Isaac.

Climax: Verses 15–18: God reiterates his promise—now sworn by God himself and confirmed through Abraham’s faithful obedience—that God will multiply Abraham’s offspring through his beloved son Isaac, like the stars and the sand, to bless all nations.

Main point: The God of Abraham can be trusted to keep his word, even if doing so requires him to raise the dead or put his own reputation on the line with the unseen future.

Notes: It’s tempting to place the climax at verses 11–12, where the angel prevents Abraham from killing Isaac or at verses 13–14, where the Lord provides a substitute sacrifice for Isaac. But neither of those events overturns the narrative’s chief conflict introduced in verse 2.

Therefore, verses 15–18 are more accurately considered the plot’s climax. In addition, the new setting of verses 20–24 (verses which are terribly easy to ignore) draws explicit attention to the twelve sons of Abraham’s brother Nahor. Abraham still has only two sons—one of which is the son of promise—while his brother appears to be growing quickly into a great nation of his own. This highlights the nature of Abraham’s faith in promises he cannot yet see and which he has not yet received.

Genesis 23

Conflict: Verse 4: Abraham vs. his lack of land ownership. Abraham can see the entire land before him, but will he ever own any of it as God has promised?

Promise under consideration: Abraham will become a great nation dwelling in the entire land of Canaan.

Climax: Verses 17–18: Ephron’s field in Machpelah, along with its cave and trees, is deeded over to Abraham legally and publicly as a burial ground for his dead.

Main point: Abraham’s faith in God’s promise of the land led him to secure a down payment of one small plot that could be enjoyed only in death.

Notes: This strange story is bookended by the famous episodes of Isaac’s sacrifice (Gen 22) and Isaac’s wife (Gen 24). To figure out what to do with it, it’s important to recognize the context of Abraham’s future-looking faith. God will provide a lamb in place of his son, and God will provide a daughter-in-law so the promised offspring can come.

Therefore, God will also follow through on his promise to give the land. Resist the urge to make this story about bereavement, as the loss of Sarah—however tragic—provides only a brief setting (v.2) for the extensive haggling over the field’s purchase (vv.3–16). Abraham’s faith looks far enough into the future that he is willing to pay a princely sum (vv.15–16) for something he can enjoy only in death (Heb 11:13–16).

And while Abraham, despite the promise to own all of Canaan, only ever owned this one burial ground, his descendant Jesus didn’t even own his burial ground (Matt 27:59–60). Yet Jesus endured in trusting God’s promises to him so all who trust in him could be raised to new life with him forever.

Genesis 24

Conflict: Verses 3–8: Promise of offspring vs. promise of land. Will Abraham’s son have to marry a Canaanite in order to stay in the land, or will he have to leave the land in order to find a more fitting mother for the offspring of promise?

Promise under consideration: Both promises of land and offspring are in play, though the chief promise thrown into question is the promise of offspring (which requires Isaac to first get married).

Climax: Verse 67: Isaac brings Rebekah into his mother’s tent (in the land of Canaan). She becomes his wife, and he loves her.

Main point: When God’s promises appear to be in conflict with one another, God himself will make a way to bring all to fulfillment.

Notes: Review the rising action (verses 9 through 66) and observe how many times the Lord himself is credited with each turn of events. The story of the servant meeting Rebekah at the well is told twice, in order to drive home the point (see especially vv. 26–27 and 48). Yahweh brings not one but both promises to partial fulfillment on account of his “steadfast love and faithfulness” toward Abraham (v.27).

This inspires the servant to ask Laban to imitate such “steadfast love and faithfulness” toward Abraham (v.49). And note the closing resolution. It does not say, “So Isaac found the wife he longed for,” but, “So Isaac was comforted after his mother’s death” (v.67b). In other words, upon Sarah’s death, there were no matriarchs of promise living in the family’s camp. But with Rebekah’s arrival, the entourage has obtained exactly that.

***

This article was originally published in the September/October issue of Bible Study Magazine. Slight adjustments, such as title and subheadings, may be the addition of an editor.

Related resources