I was just having lunch with some pastors, and we were having a friendly disagreement over exegesis. One experienced expositor said, “The Holy Spirit chose precisely this word and not another, so it must have special significance.” I said, “Yes, but we can’t overinterpret: Greek is a human language; it’s not some perfectly precise mathematics problem.”

As is often the case, I think both of us preachers were right. Each of us was merely reflecting his particular calling.

The older pastor has a blessedly multicultural congregation containing people for whom English is a second language: his calling is to help them read the Bible more carefully in an unfamiliar tongue.

I’m a writer and editor producing resources for careful teachers like him, teachers who do know the biblical text well: my calling includes helping them make sure they don’t make the Bible be more specific than it was inspired to be.

Overspecifying the biblical text

Just last year I came across an example of a Bible interpreter reading too much into the specific word choice of Paul in Titus 2:4 when he tells the older women to “train the young women to love their husbands and children.” This conference speaker told a large gathering that since women are to be φιλάνδρους (philandrous), lovers of their husbands, and φιλοτέκνους (philoteknous), lovers of their children—and since φιλέω (phileo) love is friendship love, wives and mothers are supposed to be “friends” with their husbands and children.

Now it may be true that friendship love between husbands and wives and between mothers and children is a good thing. But let’s explore this idea.

I think C. S. Lewis was right to say that lovers’ fundamental posture is looking at one another, while friends’ fundamental posture is looking side by side at some mutual interest. And there’s certainly a lot of both in my relationship with my excellent wife. If I could extrapolate from Lewis, I think the child’s fundamental posture is looking up to the parent, and I don’t know that that should ever completely go away. But I could see my children becoming my wife’s adult allies, too, in some charitable cause. We will, Lord willing, stand together looking toward some of the same Christ-honoring goals. So my wife is in very real ways my closest friend, and I hope that our children will enjoy genuine friendship with us as adults.

But I have heard a lot of wise people say that married people should not let their marriage partner take the place of all their friends; same-gender friendships are important, they say. And I’ve heard many other wise people say that parents are not to seek to be “friends” with their kids—especially if that means they try to step out of their roles of authority and protection. My wife and I dearly love our children, of course. But friends don’t typically insist that friends finish their peas lest they forego their claim to any of the vanilla ice cream. Friends don’t insist on punctual bedtimes or room- and teeth-cleaning regimens. Friends don’t correct each other’s grammar and spelling in front of others.

I am far more than friends with my wife, and we are not our kids’ “buddies.” Does Titus 2:4 really say we’re doing it wrong?

Sanity checks for odd Bible interpretations

I’m sure this conference speaker would offer appropriate caveats if asked, but his exegetical comment needs a quick sanity check.

I do several things to check odd Bible interpretations before I do the harder digging sometimes required to really evaluate them.

1. Check the translations

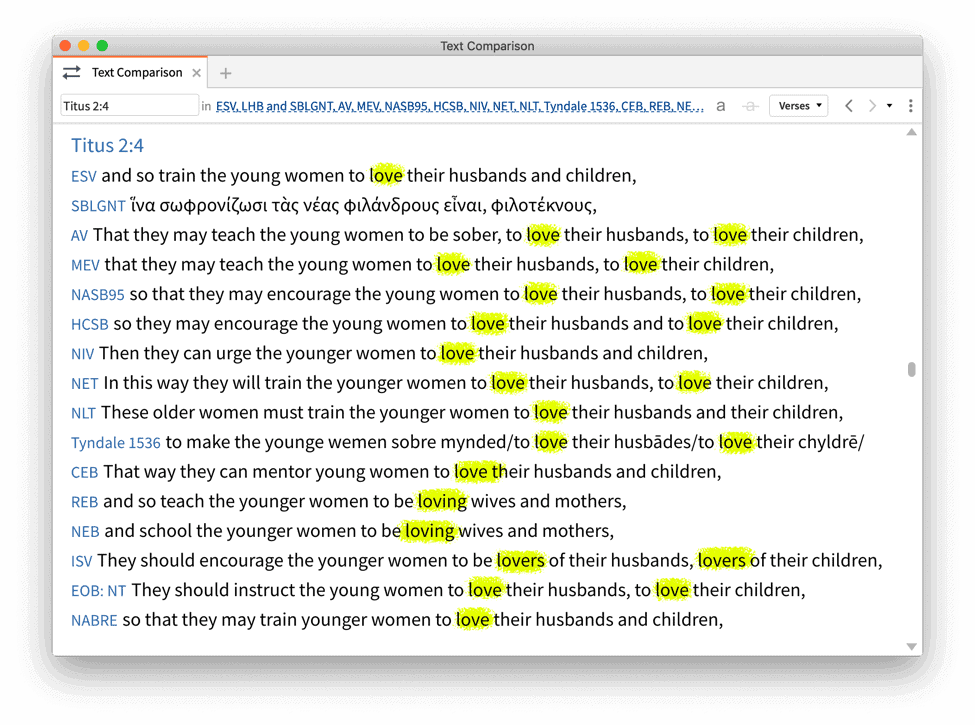

The first step I take when I hear an interpretation that sounds odd is to check some Bible translations. Sure enough, every single English Bible translation I have goes with “love” in Titus 2:4. Not one uses any form of the word “friend.” They’re all basically saying the same thing: “train/urge/instruct the young women to love their husbands and children.”

So this otherwise wonderful conference speaker who was just doing his best and upon whom I wish to cast almost no aspersions (really just one, and hardly to be noticed), was preaching a point that wasn’t demonstrable from any of the translations in his hearers’ laps. Wiser men than me—particularly Moisés Silva and Rod Decker—have warned against doing this. It’s not intended this way at all, I know, but citing Greek for a preaching point is still pulling rank in a way I think one ought to reserve for kind of never. Who can disagree with a point made from a language they cannot read?

2. Apply the method of interpretation to the rest of the Bible

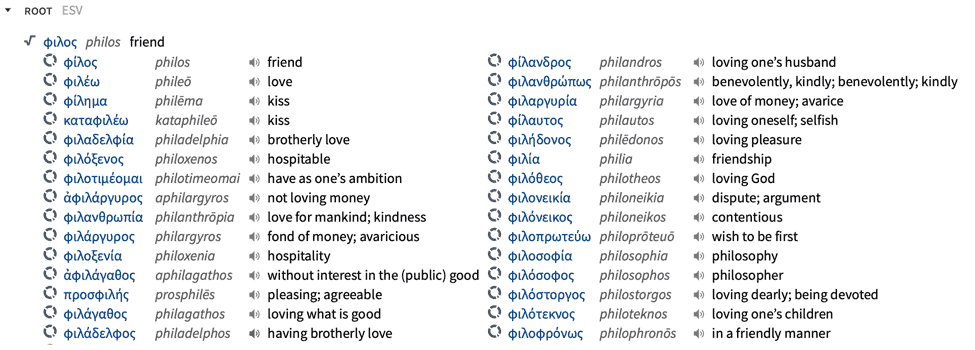

Any time I hear someone treat Greek this way, I want to know: “Does this method of interpretation work elsewhere?” There are multiple words in the New Testament that derive from the φιλ- (phil-) root or have it as part of a combining form. I can right click on “love their children” in the text in Logos and bring up a Bible Word Study showing me all of them. The Logos Bible Word study lists what lexicographers call a “whole mess” of phil- words:

Do they all carry some “core idea” of “friendship”?

Is this the way we ought to translate these verses with phil- words?

- When you pray, you must not be like the hypocrites. For they are friends with standing and praying in the synagogues and at the street corners, that they may be seen by others. (Matt 6:5)

- The Father is friends with the Son and shows him all that he himself is doing. (John 5:20)

- Whoever is friends with his life loses it. (John 12:25)

- If anyone is not friends with the Lord, let him be accursed. (1 Cor 16:22)

- In the last days . . . people will be friends with themselves, friends with money, proud, arrogant, abusive . . . (2 Tim 3:1–2)

And I could add: does Philip really mean “friend of horses” (Matt 10:3; etc.)? I don’t think that works.

There are times when words in the φιλ- group clearly mean “friend” or “friendship.” Φιλος (philos) is frequently translated “friend” in the New Testament, of course. Jesus is ridiculed for being “a friend [philos] of tax collectors and sinners” (Matt 11:19).

And there are times when the φιλ- (phil-) prefix, in context, is certainly consonant with friendship love. Julius was indeed showing himself to be a “friend of mankind” (φιλανθρώπως, philanthropos) in Acts 27:3 by treating Paul kindly. We are indeed supposed to be friendly with strangers (φιλοξενίαν, philoxenian) as Paul tells us in Romans 12:13. And when Paul says, “love [φιλόστοργοι, philostorgoi] one another with brotherly love [φιλαδελφίᾳ, philadelphia],” I can hear some friendly overtones in those words.

But Greek is not math, so to say that the φιλ- (phil-) root includes some “core idea” of “friendship” every time it occurs is to treat Greek like a secret code and not a language. Usage and context tell you what a word means, and if the idea of friendship doesn’t show up regularly in a word’s usage and isn’t demanded by a given context, it probably wasn’t intended by the writer.

Ἀγάπη (agape) is a synonym of φιλία (philia). They both mean “love.” However, that there are far fewer words in the ἀγάπη (agape) word group.

My hypothesis, as someone who wrote a dissertation that dealt heavily with emotion/affection words in the New Testament, especially ἀγάπη (agape), is that there are far more phil- words not because phil- is a specific love the NT writers wanted to call on, but simply 1) because phil- is an older root and 2) because phil- combines so much more easily with other words. It’s kind of like Watergate, the name of that prototypical media-frothing scandal that bequeathed to us the “-gate” suffix. You can attach it to any word and get a new and useful combining form. We’ve got Deflategate and Servergate; the other day while riding in my Volkswagen I heard the radio announcer mention Dieselgate.

Likewise, tack the phil- root on anything and you get “Lover of X.” We still do it today: philosopher, philanderer, philanthropist, bibliophile, Anglophile, spasmophilia (somebody please stop me now). And yet we don’t use the agap- root: agapasopher and Anglagape just aren’t doin’ it for me.

Have I nerded out enough? I’m simply arguing that the idea of friendship is not automatically included every time you see phil- or -phil- in the New Testament. If there’s a core idea, it’s just “love” or “like.”

3. Check the commentaries

A pastor friend emailed me not long ago hoping that some nicety in the Greek might back up an interpretation he really wanted to make. He is quite a skilled interpreter himself; he knew he wasn’t really seeing the evidence for his interpretation—but he hoped I would! He also showed his integrity by refusing to stand up before his people and preach that point when I and the other person he checked with both felt it was too much of a stretch.

One thing he said to me was that he couldn’t find a commentary that took his point of view, and this caused him to want to back off. I think that’s healthy. Commentaries aren’t always right, but they aren’t always wrong, either. And if not a single one takes your interpretation, the path of humility at the very least requires you to acknowledge this fact in your sermon. You probably ought to go a bit further down that not-well-trodden path and just drop the point altogether.

Sure enough, I ran through a big chunk of my Titus commentaries—including Towner (NICNT), Knight (NIGTC), Griffin (NAC), Calvin, Yarbrough (PNTC), Mounce (WBC), Marshall (ICC), Guthrie (TNTC), Stott (BST), and more (one reason I love Logos is that I can run big plebiscites like this so quickly through the Passage Guide)—and I couldn’t find a single one that suggested that “lovers of their husbands and children” had a friendship component in it.

Robert Yarbrough actually commented,

The word for “lovers of children,” like “loving toward husbands,” is nonexistent elsewhere in the New Testament and [Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Old Testament]. But its meaning is not in question. (PNTC, 514)

Questions to ask

When you take something bad away from someone, I’ve always been told that you should try to replace it with something good. Without giving answers, per se, I want to pose some questions that I think would be far more fruitful avenues for a sermon or Sunday School lesson than a doubtful and invisible point of Greek semantics. I think the textual-level meaning of Titus 2:4 is so clear as to need very little explanation. I think the preacher’s job, in this case, is more likely to come on a different level of meaning—the one we call application.

There are indeed questions one could ask. Here’s what I want to know: How are older women supposed to fulfill Titus 2:4 when it is so easy for a kind suggestion to feel like a fifteen-ton weight of condemnation to a young mom? (Dear, would you like some tips on how to keep your child quiet during church?) One might ask Paul, “Why not instead tell older women to give younger women a ‘get-out-of-childcare-free’ card for an afternoon?” All this would be worth exploring in a sermon. I guarantee that younger and older women would perk up. (My wife, a young mom, suggests that the main application is actually for younger women: they should seek out advice.)

And here’s another question: What does it mean to teach young women to love their husbands and children, given that the Bible also employs the concept of “natural affection” (Rom 1:31 KJV), a love which the vast majority of wives and mothers I’ve met seem to possess in great abundance with no teaching or urging needed? Bill Mounce had a good suggestion for that one. He said that teaching younger women to love their husbands was “especially appropriate in a culture where husbands were not chosen by the wife” (WBC, 411). That’s worth exploring—how does the verse apply, then, in a culture of love marriages?

And if you want modern people to perk up, quote Donald Guthrie, who says that the two phil- words in Titus 2:4 are there because the love they name cannot be “taken for granted, especially in our modern age when the divorce rate is rapidly rising and when the care of children so often comes second to careers” (NBC, 1313). I’ll leave this hot potato to you, pastor. (A tip: quote Anne-Marie Slaughter.)

Conclusion

By taking away a nifty exegetical move from our friend the conference speaker, I am not leaving him with nothing to say. Explaining, illustrating, and (especially) applying Titus 2:4 will easily fill one’s time—and produce interesting challenges that a Spirit-gifted Bible teacher will, Lord willing, handle with love, skill, and wisdom.

Take it from me, an euexegesiphile.

Related articles

- A Visual Guide to Choosing the Best Bible Translation

- How to Choose a Bible Translation

- The Pitfalls of One-Sided Bible Interpretation

- Bad Bible Interpretation Really Can Hurt People

- How to Use Commentaries as Tools for Discovery

- All About Hermeneutics: A Guide to Interpreting God’s Word Faithfully