Psalm 37:8 is one of the most important illustrations of the most important concept in my book, Authorized: The Use and Misuse of the King James Bible.

As I’ve been working on promoting the book, I’ve been talking about Psalm 37:8 in the KJV again and again. I’ve recited it probably 50 times to various people in the last year as I’ve explained my project:

Cease from anger and forsake wrath; fret not thyself in any wise to do evil. (Psalm 37:8 KJV)

But on Sunday at my church we read through the entire psalm in a contemporary translation and I, to my chagrin, noticed something: I’d spent so much time quoting the verse that I’d forgotten the context. I’d violated the cardinal rule of Bible interpretation. Bad Bible reader! Bad!

By itself Psalm 37:8 sounds oracular, proverbial. It sounds like a memory verse for a guy who is prone to blowing up at his kids. At least the first half of the verse sounds good for that purpose:

Cease from anger and forsake wrath.

The second half of the verse—again, taken by itself—sounds like a memory verse for someone who can’t stop worrying. The passage of years has made the English in this clause rather difficult to follow (impossible, I’d say, hence the illustration in Authorized), but “don’t worry” is basically what I’m getting out of it:

Fret not thyself in any wise to do evil.

If you feel that this is a slightly odd or random juxtaposition—don’t be angry; don’t worry—you’ve picked up a clue that you’re missing some context.

That’s because proverbs do not usually lurch from one topic (anger) to another (worry) for no reason. The two halves of a Hebrew verset are normally linked conceptually, with something stronger than “here are two random sins you should not commit.” So where’s the link here?

Well, the two concepts in this verse are linked, but to find that link you have to broaden your reading out to the context.

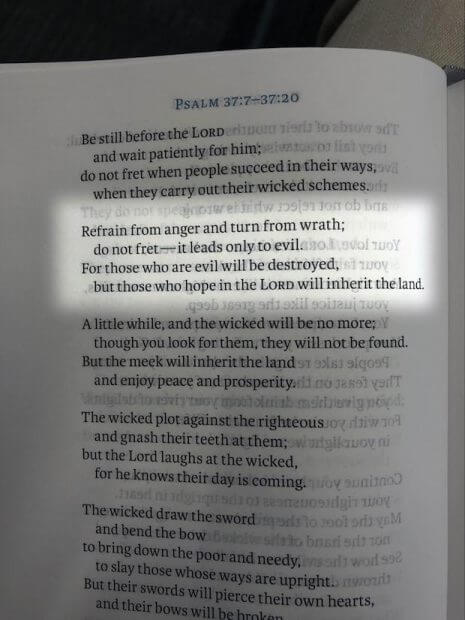

Looking at the whole paragraph is a great start. Take a look at how the NIV Reader’s Bible I had at church on Sunday formats verse 8 together with two more lines from verse 9:

Psalm 37:8 starts to make more sense when considered in light of its paragraph. The anger and worry in those first two lines are related to the work of the evildoers in the third line. Believers in the one true God don’t need to be angry at such people, because they “will be destroyed.” They don’t need to worry in the face of that evil, because “those who hope in the Lord will inherit the land.”

Of course, that’s what the whole of Psalm 37 is about: the faithful and hopeful way righteous people should respond when it appears that the wicked are getting the upper hand. The command in that verse I’ve been repeating—“Cease from anger and forsake wrath”—is not a catch-all forbidding every kind of anger: anger against kids, anger against dumb drivers, anger against NBA refs. No, the anger the psalmist is discouraging is the anger that wells up when you watch the wicked get away with wickedness—“when people,” as the previous paragraph says, “carry out their wicked schemes.”

Use

The rest of Scripture shows that some righteous anger is good: the Levite Phinehas’ angry zeal for righteousness (see Numbers 25) led him to perform a violent act of retribution that pleased the Lord and turned back divine wrath against a deeply sinful Israelite nation.

But I’ve always felt it helpful to remember, both as a personal and a hermeneutical rule, Paul’s words: “Don’t let the sun go down on your wrath” (Eph 4:26). I think it was okay for Phinehas to be angry (and for imprecatory psalmists, and for Jesus when he denounced the Pharisees and cleansed the temple) because he didn’t hold on to his anger. If he had not been capable of doing something righteous with that anger, he would have had to simmer down and leave the problem in God’s hands. No one is supposed to maintain a state of anger or worry.

As I sat listening to my pastor read with feeling and expression through the entire psalm, I thought to myself, Psalm 37:8 wipes out a ton of talk radio. I’m not picking on conservatives or liberals; both of them seem to me to be guilty of whipping up anger at their demonic enemies and stirring up worry over their terrible machinations. Enemies are real; machinations happen—and the Bible urges us to take up the cause of the oppressed. But this verse, and the whole psalm, specifically tell us not to be angered by the wicked or worry about them in an ongoing way—because “their day is coming.”

What would a political TV show look like if the host were guided by Psalm 37? The show would not deny the reality of evil or encourage an escapist quietude. It just wouldn’t foment a bunch of alarm—anger and worry.

Conclusion

We don’t check the context of a biblical statement just because the Bible has more to tell us, although that’s always true. We check it because we won’t get what it’s telling us in the first place unless we pay careful attention to the flow of thought in a given biblical passage.

Be a good Bible reader.

***