I was looking for a Mother’s Day gift and I stumbled across a quotation on the website of a local massage therapist:

I’m a huge Lewis fan, and I immediately said to myself, C.S. Lewis never said that. I just knew.

First a techie lesson on how I confirmed my suspicion, then a few biblical and theological reflections on what it means to know a writer’s voice.

Searching for Lewis

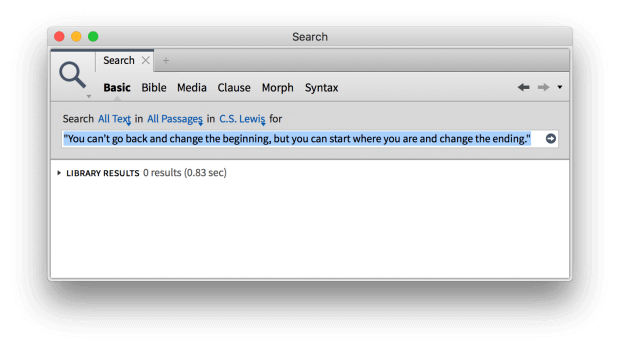

I happen to have the C.S. Lewis collection in Logos along with lots of his books; I’ve also made a “collection” within Logos including all the Lewis titles I own. I searched for this sentence in that collection, using quotation marks so I would get the exact words.

Nothing:

Then I searched without quotation marks; I got search hits for many of the words, but I didn’t find the quote:

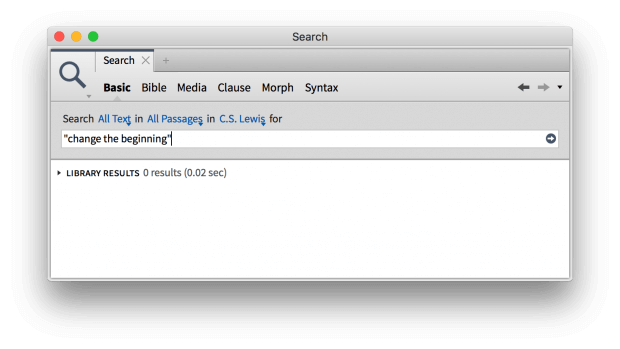

I also searched for individual portions of the quote with and without quotation marks. Nothing, nothing, nothing:

The internet found nothing either. Apparently, however, Lewis has joined Ben Franklin, Mark Twain, and Abraham Lincoln as a popular source for misattributed quotes. (That’s an honor, I think, a sign of his stature as a prose stylist and epigrammatist.) One site features basically the same sentiments with different words and attributes them to Lewis, but Quote Investigator attributes the quotation to multiple possible authors—C.S. Lewis not included. It’s often easy enough to prove that a given writer said something; it’s generally hard to prove absolutely that he did not. But all of these signs point to no, Lewis didn’t say these words.

Lewis’ voice

But, really, I didn’t need much confirmation of something I already knew. I have spent countless hours reading and rereading Lewis: I know his voice, I know his theology. Lewis wasn’t prone to pablum in either department. I find it difficult to believe that many of his quotes, even lifted out of context, would appeal to the crowd interested in spreading bromide-laced self-help memes.

Isn’t this interesting: a guy who died 17 years before I was born has left patterns of ink on paper (turned later to pixels on screen) that have formed a definite image of their author in my mind, so definite that I had an immediate, emotional reaction to a misattributed quote. I know C.S. Lewis far better than I know my own grandfathers.

Knowing a person through writing

I can’t help wondering, Do I know the God of the Bible this well? I hope so. I hope that after the hours I’ve spent studying Scripture in my lifetime, I could see a saying like “Everything you need to accomplish your goals is already in you —God” on a massage therapist’s website and conclude immediately, God would never say that!

Knowing God’s voice

Let’s try you out: what’s your gut reaction to these real-life internet memes?

Someone who’s spent countless hours reading and reading God will know his voice and know his selfology. That someone will have to say after reading these memes, God never said that!

God did say the middle one in a definite sense, of course. He just didn’t say it to any random person who happens upon the meme. He said it in a specific place to a specific people: at the edge of the Red Sea to a bunch of terrified ex-slaves. If they had shared this meme on Facebook, some of Pharaoh’s soldiers might have liked and shared it—and that would have been weird. The promise was not to us, even if it is for us in a more general way. Making it a meme is inviting, almost demanding, a misreading. And I’m saying you can know this—or at least sense it—before you can prove it, by knowing the “voice” of God in Scripture.

Knowing Paul’s voice

I also think you can come to know the voices of individual authors. I think it is admissible evidence in the did-Paul-write-Hebrews debate for someone to say, “It just doesn’t sound like Paul”—or, conversely, “Yes huh!” Me personally, I’m on the “Nuh-unh” side. The author of Hebrews just doesn’t seem to me to have the same cast of mind as Paul, although there are clear similarities. Paul is more passionate and personal, even in letters which appear to have been aimed at a general audience, like Ephesians. I also think that leaning on his apostleship is part of his voice, something he doesn’t do in Hebrews.

Knowing Jesus’ voice vs. Aslan’s

Final example. Ironically enough, though I hear much of Jesus in Aslan, I’ve always felt that Lewis’ fictional “supposal”—what would Christ be like if there were a world where animals could talk?—doesn’t quite capture Jesus’ voice. I love Narnia, don’t get me wrong. But I’ve always felt that Aslan was a little bit too tame, and in two respects:

1) At the end of each story, you feel some satisfaction that you understand what Aslan does, even if in the middle of The Horse and His Boy his comings and goings are mysterious. I don’t think you always get that aha! moment with Jesus. He truly isn’t a tame Lion of Judah. My hope is pointed toward that eschatological aha! day when I will know as I am known.

2) Likewise, I can understand what Aslan says. I’m never left scratching my head thinking, “What did he mean by that?” or “Did he really just say that?” With Jesus, however, it’s “Give to whoever asks of you,” and it’s “Love your neighbor as yourself.” And I’m left thinking, “Wait, what? How could he possibly have meant that?!” Those aren’t just profoundly countercultural commands; they’re profoundly counter-human. And these are among his simpler sayings. As many have said, it’s not what I don’t understand in the Bible that bothers me; it’s what I do understand and find it hard to obey.

Conclusion

Theologians such as N.T. Wright and Kevin Vanhoozer have used the “drama” metaphor to shed light on the Christian life. We’re in the second-to-last act of a play for which the other acts are already written. Our job is to play our parts, extempore, in such a way as to show continuity with the other acts. We can’t do that if we don’t know them intimately.

The strength of the evangelical tradition is that, ideally, everybody in it is supposed to be gaining more and more familiarity with the voice of God—and of Jesus, and of Paul—through regular study of Scripture. If this kind of intuitive familiarity can be achieved with C.S. Lewis, it can be achieved with the God in whose image we are made. He’s made himself known; he wants to be known. That’s the point of the Bible.

***

For more posts about C. S. Lewis, see below:

- Look. Listen. Receive. C.S. Lewis on Reading

- C.S. Lewis’ Ingenious Apologetic of Longing

- C.S. Lewis: An Appreciation

- Men Without Chests: Lewis, Relativism, and the Soul of Christianity

- C.S. Lewis as Literary Critic and Medieval Scholar

- Reconciliation: Reflecting God’s Fullness Together

- 4 Ways C.S. Lewis Can Shape Your Faith: Insights from a Scholar

- 3 Simple Reasons You Can’t Dismiss Miracles in the Bible

- The Only Three Kinds of Things Anyone Need Ever Do

- C.S. Lewis: A Lutheran Appreciation

- Why We Do What We Do: C.S. Lewis on Motivation