“Repent, for the kingdom of heaven has come near.”

—Matthew 3:2 NIV

So begins the ministry of Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew. And this theme, repentance, occurs frequently in the early chapters of all the Synoptic Gospels. In fact, the ministry of John the Baptist is so closely tied to the teaching of repentance that systematic theologian Millard Erickson says, “Repentance was virtually the entirety of John the Baptist’s message.”1

Far from receding after the Gospels, the theme of repentance continues throughout the book of Acts. When a guilty crowd asked how they should respond to their complicity in the death of Jesus, their Messiah, Peter commanded them, “Repent and be baptized, every one of you, in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins. And you will receive the gift of the Holy Spirit” (Acts 2:38).

Later, Paul, preaching to Greeks in Athens, confirmed that repentance is necessary for all humanity: “Now he commands all people everywhere to repent” (Acts 17:30b; cf. Acts 26:20).

Though less in number than those of the Gospels and Acts, the references to repentance in the New Testament epistolary literature are also impressive. For example, Paul highlights that God’s patience in withholding deserved judgment derives from mercy and a desire to see his enemies repent and be spared judgment (Rom 2:4). And in 2 Corinthians, Paul distinguishes a type of sorrow from true repentance, revealing that “godly sorrow brings repentance that leads to salvation” (7:10a). Near the end of his ministry, Paul instructs Timothy how to respond to enemies with grace, resting in “hope that God will grant them repentance leading them to a knowledge of the truth” and thereby “escape from the trap of the devil” (2 Tim 2:25).

Finally, the book of Revelation unveils that throughout the judgments of God, the sin of humanity was multiplied in that “they did not repent” (Rev 9:20, 21; 16:9, 11).

This brief overview of repentance in the New Testament literature shows the significance of the concept. Repentance is central to the teaching of Jesus, the salvation Jesus offered, the reception of the Holy Spirit, and the judgment to come. Considering its importance, it is critical that we understand the meaning of “repentance.”

Getting specific

Some readers might wonder why I have chosen to start our consideration of repentance in the New Testament instead of the Old. Surely, the concept exists in the Hebrew Bible: Psalm 51 may be the best expression of repentance in all of Scripture.

Of course, this is merely a short article and cannot encompass all that could be said about repentance. (Those desiring a fuller treatment should see Mark Boda’s excellent work, Return to Me: A Biblical Theology of Repentance.) So I am aiming at something narrower: I want to examine the meaning of the specific Greek word most often translated “repentance.” That would be μετάνοια (metanoia).2

It is important to note that we are seeking here to understand the use of this Greek word, not the broader theological concept of “repentance,” which in English may have various senses based on the theological tradition of the reader.3 In other words, I wanted to get to the essence not of what English speakers may mean by “repentance,” but what the biblical authors meant when they spoke of repentance (i.e., μετάνοια [metanoia]).4

The essence of repentance

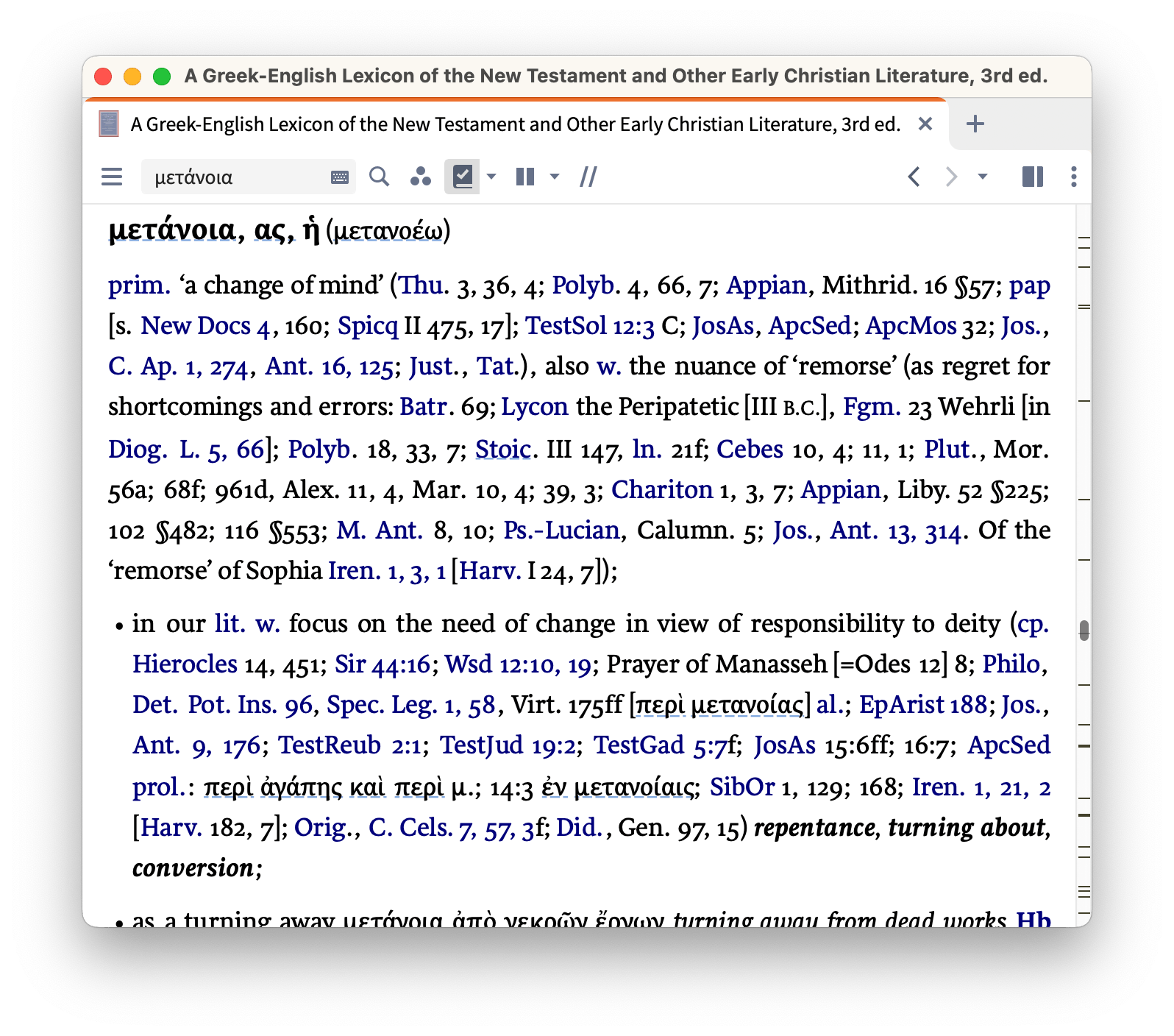

One of the historic debates over repentance concerns what exactly it includes. Some have suggested it is merely mental assent, a change of mind. Consulting an authoritative Koine Greek dictionary, we have reason to think this is a good initial definition, for BDAG says that μετάνοια refers “primarily to a change of mind.” Nevertheless, BDAG goes on to note that the New Testament use focuses more on “the need for change in view of responsibility to deity.”5

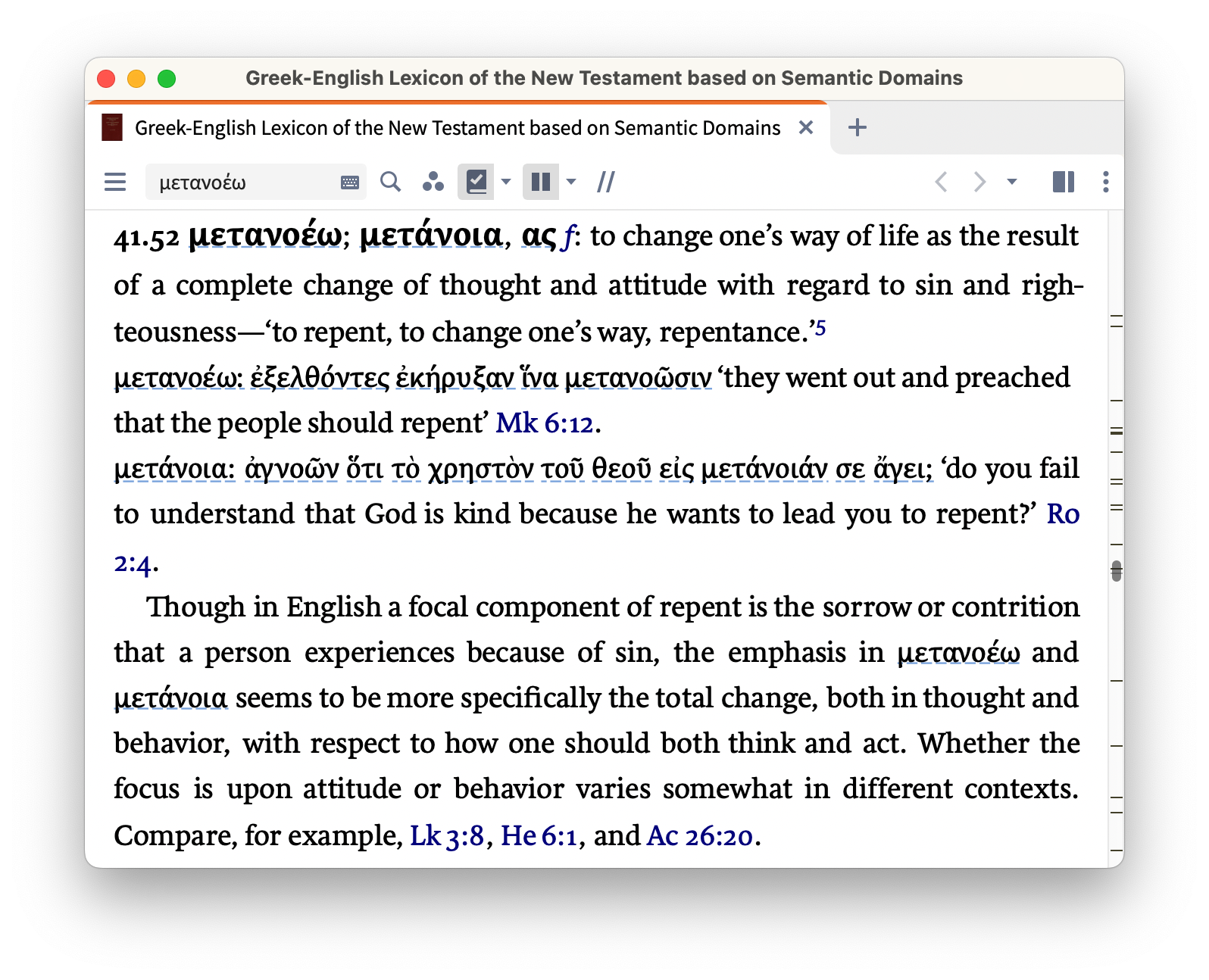

Louw and Nida agree with this further definition, noting that these Greek terms (the noun and verb forms) refer to altering “one’s way of life as the result of a complete change of thought and attitude with regard to sin and righteousness.”6

The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology and Exegesis (NIDNTTE) and the Theological Dictionary of New Testament (TDNT) trace these words from classical Greek to their use in the New Testament. They agree that the words in Classical Greek focused on a change of mind. Even the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Old Testament, primarily used μετάνοια in this way.

However, during the flowering of intertestamental Jewish literature, a shift took place7—a shift that TDNT refers to as a “break-through.”8

This shift is found primarily in the works of Philo and Josephus, who collectively use the words μετάνοια (metanoia) and μετανοέω (metanoeo) around 140 times. For Philo, the “radical turning to God” means that “the reality of life must correspond at once to the reconstruction of mind. A sinless walk must replace the former sinning.”9 Josephus likewise used these words to refer to a changed mind resulting in “an alteration of will or purpose which is then translated into action.”10 In summary, these words shifted in their semantic range from the Classical period to the Koine period. Originally, they referred to what their etymology suggests: a change of mind. This is a meaning the word never really abandoned. Nevertheless, more was added to the meaning over time, with it being used in the Koine period to refer to the changed mind that resulted in a definitive change of the direction of one’s life, specifically regarding a posture towards God and sin (i.e., a turning from sin to God).

Defining repentance in the New Testament

The following is my own attempt to define the concept of repentance: repentance is the result of encountering truth that leads to a changed mind, an affected heart, and a revolutionized life.11

The above definition seeks to express the reality that repentance touches on all three aspects of our humanity: intellectual, affectional, and volitional.12

The two elements that are generally debated are the latter two. But all three are a triad that cannot successfully be separated.13

That repentance is an intellectual event hardly needs to be defended. As was noted above, this is the classic sense of the Greek words we are considering. It is also assumed each time the Scripture calls for repentance (Matt 4:17; Acts 2:38, 17:30; Rev 2:16). The assumption is that with the reception of divine teaching, the listener must embrace this knowledge. That this repentance is an affectional event is more debated, yet it is borne out by the biblical data. By “affections,” I speak of “strong inclinations of the soul that are manifested in thinking, feeling and acting.”14

When Jesus was chastising Chorazin and Bethsaida for their lack of repentance, he noted that Tyre and Sidon, had they seen the same works, would have “repented long ago in sackcloth and ashes” (Matt 11:21; Luke 10:13). A perusal of the Old Testament indicates the use of sackcloth (Gen 37:34; Ps 30:11; Jer 4:8) especially when combined with ashes (Esth 4:1) is a sign of deep internal grief.

Paul’s most extended consideration of repentance verifies the place of the affections within the concept. In 2 Corinthians 7, Paul is speaking of a difficult matter he had to address in the church. Their repentant response gladdened Paul’s heart. What interests us is Paul’s two statements: “Sorrow led you to repentance,” and, “Godly sorrow brings repentance that leads to salvation” (2 Cor 7:9–10).15 Thus, the Corinthians were brought to repentance by godly sorrow, a deeply affective experience.16 The response of the Corinthians leads us to the volitional element of repentance. Paul knew that their repentance was genuine since it sprang from a godly sorrow, which produced a life change: “See what this godly sorrow has produced in you: what earnestness, what eagerness to clear yourselves … At every point you have proved yourselves to be innocent in this matter” (2 Cor 7:11).

Elsewhere, the New Testament calls for a repentance that leads to a changed life. John the Baptist appeals to his listeners to “bear fruit in keeping with repentance” (Matt 3:8; Luke 3:8). Paul adds that he told Gentiles that “they should repent and turn to God and demonstrate their repentance by their deeds” (Acts 26:20).

Conclusion

So, is repentance a change of mind or something different? In light of the above, this question is equivalent to the following: Is water hydrogen or something different? Well, yes of course it is hydrogen, but it is also more. In fact, if you only allowed hydrogen (and no oxygen) you would not have water. In the same way, if you only allow a change of mind in your definition of repentance, then you would not have biblical repentance. Repentance, biblically defined, is the result of encountering truth that leads to a changed mind, an affected heart, and a revolutionized life.

- Millard J. Erickson, Christian Theology, 3rd ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2013), 867.

- I will include the verb form, too, μετανοέω (metanoeo). But I will limit our discussion to soteriological contexts—those discussing repentance to salvation—and will therefore not consider μεταμέλομαι (metamelomai). This word is used of changing one’s mind with special regard for regret, but it does not appear in soteriological contexts (though the context of Matt 21:32 is debatable).

- Of course, such an approach has the limiting effect of overlooking those places where the concept is present, but the terminology does not exist.

- Mark Boda, one of the chief voices on repentance in church history, noted that repentance is quite divisive for it is a “theme that [provides] insight into the diversity of Christian theological traditions throughout the centuries and across the globe.” Mark J. Boda, Return to Me: A Biblical Theology of Repentance, New Studies in Biblical Theology 35 (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2015), 191.

- Walter Bauer et al., A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature, 3rd ed. (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 640.

- Johannes P. Louw and Eugene Albert Nida, Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament: Based on Semantic Domains, 2nd ed. (New York: United Bible Societies, 1996), 1:509.

- The recently published Cambridge Greek Lexicon, which provides definitions ranging from Classical to Koine Greek, confirmed this reading, noting that Classical Greek used these words in reference to a change of mind while New Testament Greek used them to refer to a more fully developed doctrine of “repentance.” James Diggle et al., eds., The Cambridge Greek Lexicon (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2021).

- Gerhard Kittel, Geoffrey William Bromiley, and Gerhard Friedrich, eds., Theological Dictionary of New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1964), 4:992.

- Kittel, Bromiley, and Friedrich, TDNT, 4:994.

- Kittel, Bromiley, and Friedrich, TDNT, 4:995.

- Wayne Grudem, speaking more on the theological concept than the use of these specific words, has a similar definition: “Repentance is a heartfelt sorrow for sin, a renouncing of it, and a sincere commitment to forsake it and walk in obedience to Christ.” Wayne Grudem, Systematic Theology: An Introduction to Biblical Doctrine (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2000), 713.

- Rolland McCune likewise argued for a tripartite definition, though he has “emotional” in place of the affectional. See Rolland D. McCune, Systematic Theology, Vol . 3: Soteriology, Ecclesiology, and Eschatology (Allen Park, MI: Detroit Baptist Theological Seminary, 1998), 64–65.

- If we were to use John Frame’s model of triads, the intellectual would be normative, the volitional would be situational, and affectional would be existential. For more on the triads, see Timothy E. Miller, The Triune God of Unity in Diversity: An Analysis of Perspectivalism, the Trinitarian Theological Method of John Frame and Vern Poythress (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2017).

- Gerald R. McDermott, The Great Theologians: A Brief Guide (Westmont, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2010), 128. For a comparison of affections and emotions, see Justin Taylor, “What Is the Difference between Affections and Emotions?,” The Gospel Coalition, May 3, 2013. https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/blogs/justin-taylor/what-is-the-difference-between-affections-and-emotions/.

- One may argue that godly sorrow precedes repentance. I would not argue against this; I would only want to add that it is also an essential component of repentance. Knowledge also precedes faith yet is an essential component of faith.

- Of course, people’s responses to grief and sorrow differ. There is no requirement for tears or wailing, which are outward manifestations of internal angst. Nevertheless, there should be internal angst, whatever outward effects these may have on the repentant individual.