In my previous article in this two-part series, I offered my thoughts on John Piper’s recent off-hand comments about Logos and BDAG. While very appreciative of Piper’s love for Logos, I argued that BDAG may be more useful to more people than his brief words on the topic suggested.

I’ll argue something similar about commentaries. Piper also said on the Pastor’s Talk podcast,

If I consult a commentary, I consult it after I’m stumped. … That’s one of the reasons I don’t bother with commentaries very much. They don’t get as far as I do, often. … My favorite commentaries are commentaries like Ellicot and Alford, because those guys pose the questions I’m stumped by. They pose serious, detailed, grammatical questions. The others, they just say things everybody sees. They all write the same things. So I’m not helped much.

Piper’s influence on me

John Piper has had an immense and positive impact on me, especially in my more formative years. He showed me the glory of God and he stoked my love for God. What could be more important? My dissertation on Paul’s Religious Affections was born out of a love for his key works (Desiring God and The Pleasures of God). He was a gateway for me to Edwards and the Augustinian tradition. He is a stupendously careful and effective reader of Scripture. But I cannot honestly say that I have followed Piper’s bent toward Greek grammatical study and away from commentaries. I’m not condemning it or disregarding it or devaluing it: I’m relativizing it to the personal gifting and interests of the exegete.

Two major influences have pushed me away from Piper’s practices with commentaries.

Barr on going from grammar to theology

One is James Barr (and others who have written in his vein, especially evangelical scholar Moisés Silva, in books like Biblical Words and Their Meaning). Barr wrote one of the most important paragraphs I’ve ever read about exegesis:

Theological thought of the type found in the NT has its characteristic linguistic expression not in the word individually but in the word-combination or sentence. … [Since] important elements in the NT vocabulary were not technical … the attempt to relate the individual word directly to the theological thought leads to the distortion of the semantic contribution made by words in contexts; the value of the context come to be seen as something contributed by the word, and then it is read into the word as its contribution where the context is in fact different. Thus the word becomes overloaded with interpretative suggestion.1

What Barr said about words I say about grammar. In my experience, preachers with Greek training want to relate individual grammatical constructions directly to theological thoughts. They do this, for example, with verb tenses. As my friend Andy Naselli says in his book Let Go and Let God: A Survey and Analysis of Keswick Theology, Keswick theologians were fond of pointing, for example, to the “punctiliar action” (think of precisely one point [Latin, punctum] on a right-to-left timeline) allegedly always indicated by the Greek aorist tense. They used this impressive grammatical datum to argue that the aorist (bolded) in Romans 6:13 speaks of a once-for-all, point-in-time act of consecration:

Do not present your members to sin as instruments for unrighteousness, but present yourselves to God as those who have been brought from death to life, and your members to God as instruments for righteousness. (Rom 6:13 ESV)

The first “present” at the beginning of the verse is in the present tense. The second is aorist. Therefore, said Keswick theologians, you’re now giving your body away continually as a tool for sin, but you’ve got to make a once-for-all decision (punctiliar aorist) to consecrate yourselves to God.

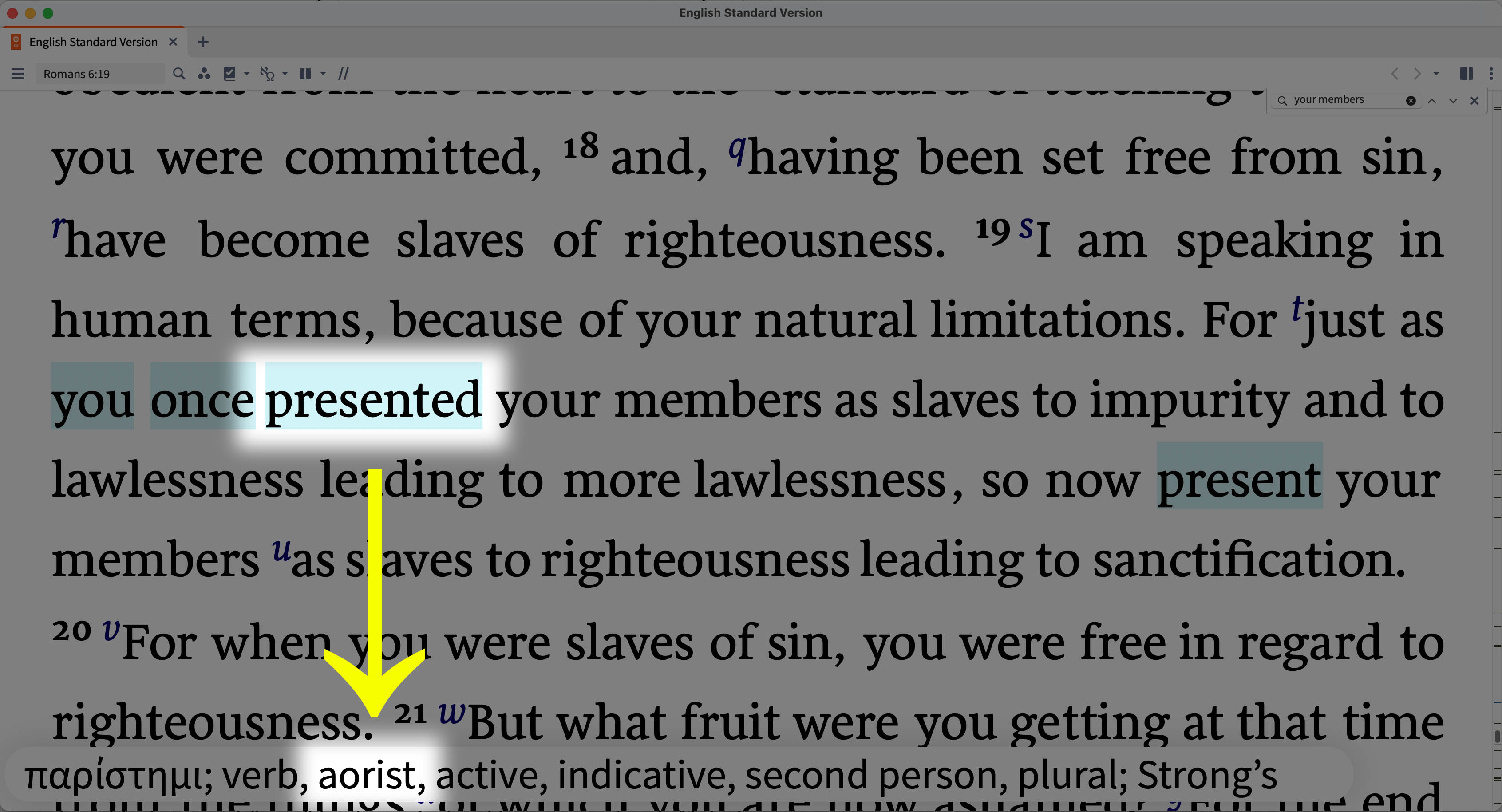

But often—using Logos to search for (or at least display) the morphological information—you can just read on a sentence or two to find a place where a nifty argument like this just doesn’t work. So it is in Romans 6, which goes on to say, “You once presented [aorist] your members as slaves to impurity and to lawlessness leading to more lawlessness.” When did such a deadly consecration occur? Was it a one-time, punctiliar action? No. It was an ongoing reality. And yet Paul used an aorist, as Logos shows with the hover a mouse:

Jesus used an aorist too, when he said, “Abide [aorist] in me” in John 15. But context makes it clear that abiding is the very definition of a non-punctiliar action. It’s the very opposite of punctiliar. (Your abiding in Christ had better not be merely punctiliar.)

I’m not commenting here on Keswick theology itself, only on the way certain of its theologians argued from grammar to theology. Nifty grammar-to-theology arguments often end up promising more than they deliver, in my experience.

Here’s my rule of NT-scholar-Rod-Decker’s thumb: you probably shouldn’t preach a point that isn’t present in your hearers’ English Bibles. If most major translations make no distinction (in English) to reflect the variation between present and aorist tenses in Romans 6:13 (in Greek), it may not really be there—or, at least, it may not be wise to preach it. Indeed, only the rather fastidious New American Standard Bible makes a distinction here; even the Literal Standard Version does not do so.

Piper

It actually just so happens that I was listening to a John Piper sermon after I wrote the first draft of this piece, and I heard this otherwise excellent, legendary preacher do what I’m describing. I didn’t go looking for this example, and I dislike disagreeing with a hero of mine such as Piper! He was actually disagreeing (mildly) with his own beloved ESV and arguing for a particular significance for a given preposition in Luke 10:27—“Love the lord with/out of [εκ, ek] your whole heart.” He pointed out this significance to the audience—which, in his defense, probably contained a noticeable percentage of people who knew Greek (it was Joel Beeke’s Puritan Conference at Grace Community Church). Piper named the Greek words at issue and drew a contrast between loving God “with” your whole heart (which would be εν, [en] and is in fact used in the parallel passage in Matthew 22) and “out of” your whole heart (which is εκ [ek], the word used in Luke 10:27).

I immediately suspected that I just couldn’t buy this interpretation: Piper was cutting too fine a distinction. (He went on to make some arguments I felt were much more solid, such as pointing out that “heart” is first in the list.)

So I checked BDAG. Sure enough, BDAG lists an instrumental use of the preposition at issue here, and it gives an example use from Luke: “Make friends by means of [εκ, ek] unrighteous mammon.” And—significantly—I couldn’t find a major translation that reflected the difference in Greek pronouns in Luke 10:27. I didn’t, don’t, and can’t quite buy Piper’s particular argument. I see εκ (ek) as being used in stylistic variation with εν (en) in that verse. (If BDAG hadn’t done this work for me, I would have used the Bible Word Study in Logos to find instrumental uses of εκ [ek] on my own.2)

It’s common enough for Bible interpreters to read very specific theology out of very arcane grammar that I have found myself instinctively going back to Barr: I place more weight on the sentence than I do on the individual parts of a sentence, including both specific words and specific grammatical points. I also place a lot of weight on paragraphs, which is the single biggest reason why I care so much about good Bible typography.

A little more nerdity before I get to my second big influence: over and over in Nigel Turner’s Syntax, which I read in its entirety and marked up extensively back in seminary, Turner would say things like this:

Already in the Koine the distinction between the relative pronoun of individual and definite reference (ὅς [hos] and ὅσος [hosos]) and that of general and indeterminate reference (ὅστις [hostis] and ὁπόσος [hoposos]) has become almost completely blurred.3

Or this:

Imperfects are retreating before aorists in the Koine.4

The pattern seemed to me to be that arcane grammatical distinctions that were once observed in classical Greek came to be eroded in the Koine Greek used in the New Testament. I speculate, but I wonder if common people ever observed all those fine distinctions. How many of us today know the official, grammar-book difference between “that” and “which”? And this very day as I write, I was in a formal public discussion with well-educated Bible nerds who repeatedly “mixed up” the words “lie” and “lay” (They said, “I want a Bible that lays flat”). I pointed this out in mock seriousness, but I knew that the distinction exists mainly in books for pedants and isn’t really true in the language as it’s used even by expert English speakers—such as the well-educated people with whom I was speaking.

Exegesis is an art and a science. And I’m genuinely grateful for those—from Keil and Deilitzsch to Steve Runge—whose strength lies in the grammatical and arcane portions of that science. They help me know the limits of where the art can bring me. And maybe I’m too grammar-skeptical. Maybe, also, it’s good to have right hands and left hands in the body—people who have a bent toward interpretive precision at the molecular level, and people who default more to the sentence.

But all I’ve just described is why my use of commentaries is different from Piper’s. In my own conservative, biblicist circles, I fear that going beyond the Bible text is a more common sin than failing to say all the text says. Other groups have different gifting and bents.

Frame

The other major influence on my exegesis whom I wish to discuss in light of Piper’s commenting on commentaries is theologian John Frame. Frame taught me that if usage determines meaning, then, to some degree, meaning is use. In other words, I put a lot of weight on what other skilled and Spirit-filled Christians over time have seen in a given passage. How have they “used” it? If no one else in the history of interpretation has come to the conclusion I’m entertaining, perhaps entertainment has too big a place in my life.5 And if no one else answers a question I have, perhaps it’s not as important as I thought.

Frame points out that if someone “understands” a given passage of Scripture but has no idea what bearing it has on his life, no idea how to—again—“use” it to increase his faith, hope, and love, or to shape his obedience, then he probably cannot say that he “understands” it.

Frame’s classic illustration is the doughnut (like his predecessor, Van Til, the brilliant Frame is fond of very accessible illustrations).

If God says “Thou shall not steal” and I take a doughnut without paying, I cannot excuse myself by saying that Scripture fails to mention doughnuts. Unless applications are as authoritative as the explicit teachings of Scripture (cf. The Westminster Confession of Faith, I, on “good and necessary consequence”), then scriptural authority becomes a dead letter. To be sure, we are fallible in determining the proper applications; but we are also fallible in translating, exegeting, and understanding the explicit statements of Scripture. The distinction between explicit statements and applications will not save us from the effects of our fallibility. Yet we must translate, exegete, and “apply”—not fearfully but confidently—because God’s Word is clear and powerful and because God gives it to us for our good.6

Here’s where my mind takes all this: God knows all the situations to which all his rules, precepts, statutes, and laws apply. He knew them when he inspired Scripture. He knows all the faithful and appropriate uses of those pieces of revelation, and he knows all the faithless and twisting (2 Pet 3:16b) uses of his words.

The tools of exegesis are all methods of doing our best, along with the illumination of the Spirit, to make faithful and appropriate use of God’s words in our respective circumstances. We read the context to make sure we’re assuming appropriate definitions of words. We study the literary genres so that we observe the patterns of meaning present therein. We learn about historical background so we can have some idea who is on the other end of the phone line as we hear Paul talking. And, yes, we observe grammatical patterns as we try to reach the authorial intent of every Bible passage.

I may seem to have gotten pretty far afield from commentaries again, but I haven’t. Here’s the connection: I look for the best signs I have that a given commentator is (and here I borrow from hermeneutical theorist and theologian Kevin Vanhoozer) a “right reader reading rightly,” and I take what that commentator says seriously. When he or she “uses” Scripture in a certain way, I take that as a weighty vote.

I can’t go as far as Augustine and one biblical scholar I interviewed once who both seemed to say that if an interpretation promotes love of God and neighbor, it’s “true.” I wouldn’t want my words to be interpreted that way; I want people to know what I meant. But I feel the pull of that Augustinian view. So I place a fair bit of weight on the small-o orthodox interpretive tradition. I doubt interpretations that have never occurred to any other Bible readers in the history of the church, and I tend to view interpretations that lots of serious, skilled Christians have held as—prima facie, in principle—acceptable. With Charles Hodge of the old Princeton Seminary, I hope I never say anything truly new.

This kind of leads me back to a more positive assessment of John Piper’s use of the εκ (ek) preposition in Luke 10:27. He has flaws and sins, as he would admit and often does, but I believe he is a right reader reading rightly. His vote is valid. I suppose we won’t find out till glory exactly who’s closest to right on such arcane questions as the intent of the variation in prepositions in Luke 10:27. Long, careful attention to accurate Bible interpretation has led me to have a sense of where our claims of knowledge need to stop. But I can’t deny that Piper has given even longer and more careful attention. God will judge.

Conclusion

For years, I kept commentary use till the end of my exegetical process—just like Piper says he does. I felt duty-bound to follow that principle. And I still think that waiting to check commentaries is the least lazy method—for me. But in recent years, I’ve realized that I truly just don’t have time to do all the exegetical prep I’d prefer to do. When I teach in the Spanish ministry or the youth group or the equipping classes or the young adult ministry at my church, I sometimes have to fit prep into the wee hours of the morning. Or I have to do what I’ve never before done: I have to use notes prepared by others.

And I figure that as long as I’m taking an interpretation that responsible people have taken, responsible Christian scholars who did have the chance to do the exegetical work in their well-appointed studies and their cushy endowed chairs, I’m probably okay. And if they all write the same things about a passage (and let me say clearly that Piper is right about this), I actually like that situation: I feel more secure having seen the Spirit guide them all into the apparent truth of that portion of his Word. And even when commentators echo each other a lot, they still often provide exegetical tidbits that are useful to me, if only in homiletics. I love checking lots of commentaries in Logos. For me and my calling, they’re a big help. I rarely use them all, but I’ll frequently use the Passage Guide to call up at least 10–15, from Calvin to NICOT.

I’m not fit to tie Piper’s homiletical shoes. I owe a great debt to him. But I’m forty-two. I don’t have much time left in this vale of tares. I have to say what I believe is true: I think my fellow conservative evangelical Bible teachers are prone to over-interpret New Testament Greek, to demand of it more precision than its authors intended. This leads me to a different use of commentaries than some of my heroes.

Related articles

- The Definitive Guide to Bible Commentaries: Types, Perspectives, and Use

- 7 of the Best Exegetical Bible Commentaries

- 10 of the Best Devotional Bible Commentaries

- James Barr, Semantics of Biblical Language (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2004), 233–34.

- And as my friend Ben Hicks pointed out to me, “Luke, Matthew, Mark, and the LXX all use different combinations of ek and en. Matthew 22:37 uses en for all three, Mark 12:30 and the LXX use ek for all the elements, and Luke begins with ek and switches to en.

- Nigel Turner, Syntax (London: T&T Clark, 1963), 47.

- Turner, Syntax, 64.

- I gave an academic paper last year, for example, in which I ran an “interpretive plebiscite” in every last one of my Psalms commentaries, checking to see whether any of them interpret Psalm 12:6–7 as KJV-Onlyists do, namely as promising the jot-and-tittle perfect preservation of the Hebrew and Greek texts of Scripture. I concluded that no one I could find came to this conclusion. A reviewer subsequently found a few obscure eighteenth-century figures who did. But the kind of people whose work is lasting enough to make it into Logos did not.

- John M. Frame, The Doctrine of the Knowledge of God: A Theology of Lordship (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 1987), 84. Incidentally, I discovered that “doughnut” is spelled inconsistently in Frame’s works—sometimes it’s “donut”; so make sure to search both spellings if you want to have a full Framean theology of this yummy treat.