Everyone knows the King James Version of the Bible was translated in 1611, but almost no one has read a 1611 KJV. Not only do the great majority of KJV editions actually come from a 1769 revision (one of a series of revisions), but even the “1611” editions available online are not perfect representations of the intentions of the KJV translators.

In an era before computers, typographical errors were introduced into the very first printed editions of the King James Bible. Subsequent printers and editors over a century and a half built up their own patina of miscellaneous, minor alterations on top of the KJV, until the text we now generally use was established by Oxford’s Benjamin Blayney almost 250 years ago.

If you want to know what the KJV translators really intended, you need the New Cambridge Paragraph Bible. Editor David Norton, like F.H.A. Scrivener before him, dedicated years of his scholarly life to blowing away “thousands of specks of dust from the received text.” He looked at the personal diaries of KJV translators. He learned Hebrew. He went to Oxford’s Bodleian library and studied the surviving notes from the translators’ work—particularly their scrawls on unbound copies of the Bishop’s Bible, which they were instructed to revise. Norton performed his task with excessive care: to call him “detail-oriented” would be like calling Paul “an influential theologian” or calling Spurgeon “good with words.”

Even though Cambridge University Press, one of two historic centers of work on the KJV, authorized Norton’s text-critical work, it has not achieved the traction it deserves. It’s been treated with suspicion by the people who might most have welcomed it, KJV-Only Christians—and ignored by most everybody else.

Those reactions may have been predictable, but they’re both wrong. Those who are KJV-Only will love the New Cambridge Paragraph Bible if they give it a chance, and through it others might just rediscover the beauty and importance of an historic English Bible translation.

Why you need the New Cambridge Paragraph Bible

All English Bible readers can benefit from the NCPB. Those who believe the KJV is the only acceptable English Bible translation should get the real deal.

And if others are going to read the KJV—and I do use it for study and comparison nearly every day—they, too, should know what the original said. Benjamin Blayney’s 1769 revision work was excellent and has become the standard KJV; the same ought to now happen with Norton’s work. Norton rightly praises Blayney’s efforts, but it’s rather arbitrary that an 18th-century revision of the KJV is the one that stuck.

Everyone who uses the KJV, and knows that that’s what they’re doing, ought to use the New Cambridge Paragraph Bible.

Making the King James Version Bible as readable as possible

People trust the KJV. I don’t treat that trust lightly, and I happen to believe that the KJV translators did excellent work. I even see significant advantages for the church—and even for the culture—when one translation rises far above the rest. But English has changed a lot in 400 years, often in subtle ways that English speakers can’t be expected to recognize. Therefore, anyone who publishes a KJV edition bears responsibility to make it as readable as possible.

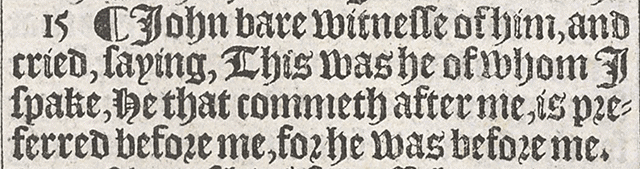

Many Bible publishers don’t do this, but Norton, working with Cambridge University Press, did. His careful philological work revealed that the KJV translators, like all writers of their day, were inconsistent in their spelling practices. So he conformed spelling to contemporary norms, but without changing archaic words. “Spake” is now “spoke.” “Shew” is now “show.” (“Saith” did not become “says,” however—that would be a major alteration of the character of the language.) This spelling update honors the authorial intention of the KJV translators while eliminating unnecessary distance between us and them, a distance which makes reading unnecessarily difficult for contemporary readers. Reading a first-edition KJV with its Gothic type and (to us) odd spelling is very distracting:

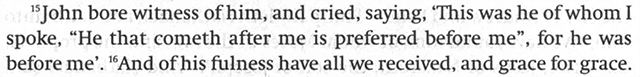

The seventeenth and eighteenth century editions themselves updated KJV spelling—witneffe became witness, commeth became cometh, loue became love—and I think we can all be thankful they did. Why not update that spelling just a bit more? No words are being changed. Here’s Norton at that same verse:

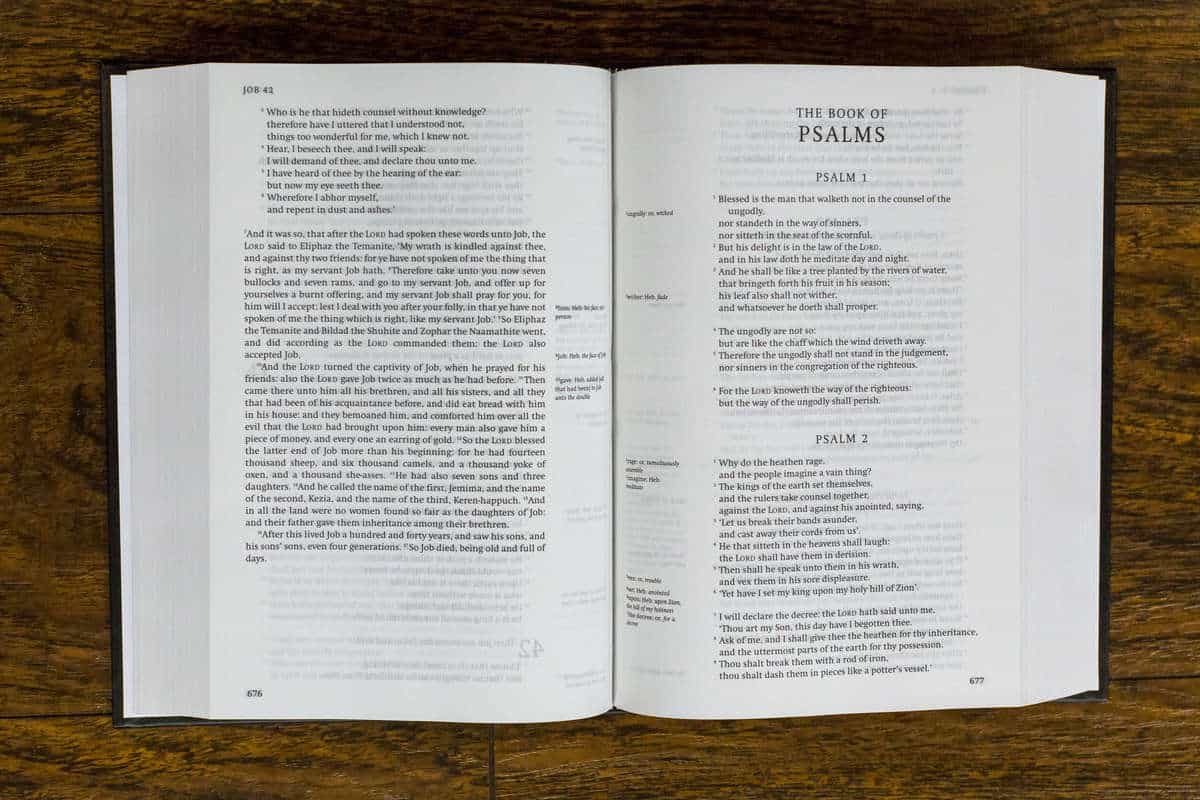

As you can see, Norton also gave careful attention to typography. That’s a big reason why his work is called a “Paragraph Bible” (the other is that he is following in the tradition of F.H.A. Scrivener’s 1873 Cambridge Paragraph Bible, another excellent scholarly edition of the KJV and a book Logos worked very hard to release in our format). Norton’s text is presented in a single-column layout which, as I’ve often argued, facilitates contextually sensitive reading. He added in paragraph breaks where the KJV lacks them (he notes that “one of the curiosities of the KJB is that there are no paragraph marks after Acts 20 [and] only one in Psalms” [49]). He laid out the poetry as poetry rather than as paragraph chunks.

Other things being equal, this layout, with both poetic lines and elegant paragraph divisions…

…is easier to read than a layout with no line or paragraph divisions, or the more common KJV layout in which every verse (an arbitrary division already) is made into a separate paragraph.

Norton also added quotation marks, a seemingly small change which is nonetheless a profound help to today’s readers. He eliminated the confusing custom of using italics to mark words supplied by the translators—a practice that, Norton argues persuasively, obstructs readers and looks like emphasis to modern eyes when that was not the KJV translators’ intent (if you think those italics are beneficial, Norton has some wise reasons to reconsider; 49, 162–163).

The KJV was itself a revision of a revision of a revision: the KJV translators were instructed to revise the 1568 Bishop Bible, which in turn revised the Great Bible, a revision of Tyndale. On the very first page the KJV proclaims that it was produced “with the former translations diligently compared and revised.” And today, nothing short of a genuine revision will make the KJV as readable as the NIV or even the ESV—which is a revision of a revision of a revision of the KJV—but Norton did everything within his power to make the text accessible to contemporary readers without revising it. The New Cambridge Paragraph Bible is a beautiful, useful volume. If Bible readers prefer the KJV, this is the edition they should read. If Bible students wish to study the KJV, this is the edition they should turn to.

The best tool for the job

I love the KJV and always will. I memorized countless verses and phrases from it as a child. But it is no longer a vernacular Bible translation and never again will be—a claim I back up in my book Authorized: The Use and Misuse of the King James Bible.

But I don’t wish to escape the influence of the venerable King James Version, even if it were possible. I am genuinely thankful for its outsize role in English Bible history. I think it has had profoundly positive effects (as any good Bible translation in any language will do, because they are God’s words). It is natural and understandable that such a Christian monolith will take time to replace. And while it still has a hold on English-speaking Christianity, we should make the KJV as accessible as possible. The New Cambridge Paragraph Bible is the best tool for that job. Both in print and in digital formats, it ought to become the new standard edition of the King James Version.

***

Watch Authorized and other Faithlife Originals with a Faithlife TV Plus free trial.