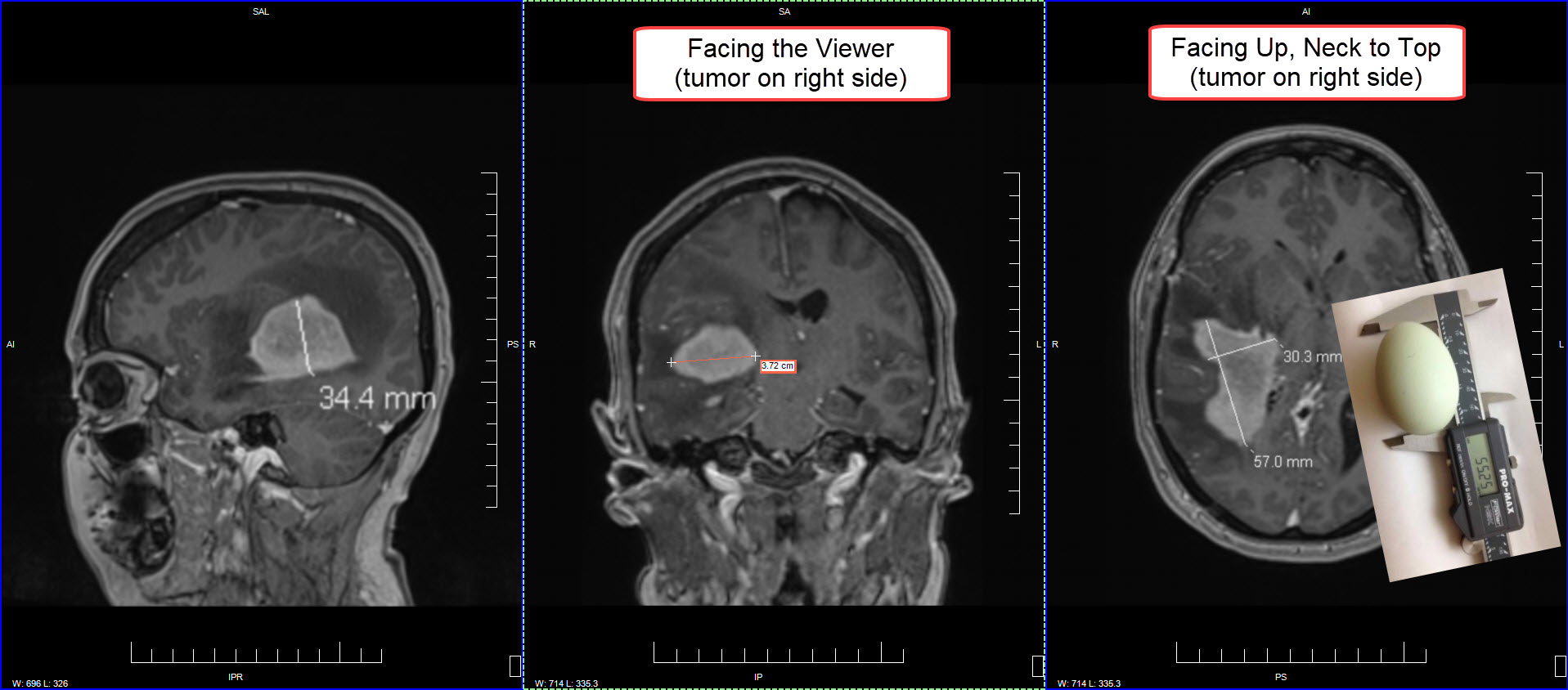

A few months ago, my wife began exhibiting some unusual neurocognitive behavior, which prompted me to take her to the emergency room. An MRI revealed she had a “quite sizable” brain tumor, to quote the doctor who broke the terrifying news.1 Days later, it was diagnosed as a lymphoma and curable (thank God), but the cancerous tumor was so large that I could see it pushing the surrounding brain matter aside in the MRI images.2

I reflected, after the discovery, upon the now easily explained changes my wife had reported in what philosophers call her qualia3—that is, her subjective conscious experiences. Prior to going to the hospital, for example, she said it felt like reality wasn’t as full or rich as usual, as if a layer or two of it were missing; and while still in the hospital awaiting her biopsy, she told me that the people around us sounded like they were talking in foreign accents, even though they weren’t. It seemed to me that my wife’s consciousness, rather than subsisting in a non-physical “soul” or “spirit” that somehow interacts with her brain, was instead the product of her brain, emergent from it—the normal functioning of its neurons interfered with by the intrusive mass.

This notion, that a human’s conscious mind is in some sense the product of one’s living, functioning brain, is a fundamental tenet of Christian physicalism. In dualism, which has been the majority report in Christian thought by far, humans are constituted ontologically of “two fundamental kinds or categories of things”:4 physical (the body) and non-physical (the soul/spirit or the soul and spirit).5 Physicalism denies this, being a form of monism, according to which “humans consist of one [kind of] substance.”6 Physicalists see human beings as constituted of only physical things and take human consciousness to be a property, function, or capacity of the living brain.7 Some physicalists are naturalists, who tend to be reductive physicalists, believing “that the person is ‘nothing but a body’” and “that human behavior can be exhaustively explained by means of genetics or neurobiology.”8 Christian physicalists, however, are nonreductive physicalists:9 We believe a human being is “a physical organism whose complex functioning, both in society and in relation to God, gives rise to ‘higher’ human capacities” that can’t be reduced to the physical, “such as morality and spirituality.”10

A recent article here at Logos’s The Lecture Hall offered a representative dualist accounting of what biblical authors mean by words translated “soul” and “spirit.”11 In this article, I wish to offer a physicalist alternative. Of course, virtually all words in any language exhibit a range of meanings. Generally speaking, however, Christian physicalism understands “soul” as referring to either the whole living person, one’s entire being, or to one’s life; and “spirit” as referring to one’s life-giving breath or to one’s mind. Let’s explore the biblical data.

As I live: “soul” (נֶ֫פֶשׁ, ψυχή) as person and life

The Old Testament word often translated “soul” is present in the beginning, where it is used of whole, embodied persons, not non-physical parts thereof. “God formed the man of dust from the ground,” Genesis reads, “and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life,” at which point “the man became a living creature [נֶ֫פֶשׁ]” (Gen 2:7). Older translations render the word here “soul” (KJV, ASV, DRB), but newer ones render it “creature” (ESV) or “being” (NASB, NIV, N/RSV, NKJV, H/CSB, NET)—in part, no doubt, because the surrounding text uses the word equally for all sorts of animals that live on land (1:24) and in the sea (1:20–21) and air (2:19). Importantly, the man’s initially lifeless body is not given or united to a נֶ֫פֶשׁ; rather, the man becomes a נֶ֫פֶשׁ when his body is animated by divine breath (a point to which we will return). As Kenneth Mathews puts it, “the breath of God energized the dormant body, which became a ‘living person.’”12

This is often how נֶ֫פֶשׁ is used of human beings, simply to mean “person.” Abram and Sarai travel with the “people [נֶ֫פֶשׁ] that they had acquired” (Gen 12:5). “All the descendants of Jacob were seventy persons [נֶ֫פֶשׁ]” (Exod 1:5). The word frequently functions as a pronoun or refers periphrastically to one’s own person—oneself—as in, “I [lit., my נֶ֫פֶשׁ] choose strangling” (Job 7:15), “delight yourselves [lit., your נֶ֫פֶשׁ] in rich food” (Isa 55:2), and, “they had obligated themselves [lit., their נֶ֫פֶשׁ]” (Esth 9:31). And it can name an indefinite person, as in, “When anyone [lit., a נֶ֫פֶשׁ] brings a grain offering” (Lev 2:1), “Whoever [lit., every נֶ֫פֶשׁ] does any work on that day” (23:30), and, “one [lit., a נֶ֫פֶשׁ] who is hungry” (Prov 27:7).

Very frequently, נֶ֫פֶשׁ means “life,” and not life in general, but an individual instance thereof13—a life, my life, one’s life. Divine messengers tell Lot, “Escape for your life [נֶ֫פֶשׁ]” (Gen 19:17). The Mosaic Law prescribes the penalty of death for murder: it is “life [נֶ֫פֶשׁ] for life [נֶ֫פֶשׁ]” (Deut 19:21). Elijah prays over a dead child, asking, “let this child’s life [נֶ֫פֶשׁ] come into him again” (1 Kgs 17:21). The biblical texts in which נֶ֫פֶשׁ carries this meaning are “numerous”;14 they constitute “many texts,” indeed “a remarkably large number.”15

The (mistaken) association of נֶ֫פֶשׁ with the concept of “soul” is probably owing to the assumption, made by later dualist readers and translators, that the soul is what grounds a person’s inner life of thought, emotion, and desire. As William Dyrness explains,

[נֶ֫פֶשׁ] is used in the sense of a throat opened in greedy need (Ps. 143:6, “appetite” in Is. 5:14). It can be the organ that drinks (Prov. 25:25) or that tastes (Prov. 16:24) or that craves (Jer. 2:24, Heb.; RSV, “heat”). Or it is simply the neck (Ps. 105:18 and Jer. 4:10, Heb.; RSV, “life”). In this sense the soul is the seat of the elemental needs of a person. By extension the word comes to mean “desire” in the sense of vital longing or striving . . . [and] the soul in the sense of the center of spiritual experiences.16

That is to say, the word’s use for “a person in need, usually in a purely physical sense,” gives rise to its use for a person with immaterial needs, emotional and spiritual.17 Or as Hans Walter Wolff puts it, “It is only a short step from the [נֶ֫פֶשׁ] as specific organ [throat] and act of desire to the extended meaning, whereby the [נֶ֫פֶשׁ] is the seat and action of other spiritual experiences and emotions as well.”18 It’s not unlike the way “heart,” literally naming the organ that pumps blood and is so vital to life, is used figuratively in expressions such as “the heart of the matter.” It simply does not follow, from the use of נֶ֫פֶשׁ as the seat of emotional needs and desires, that נֶ֫פֶשׁ refers to a non-physical substance known in English as “soul.”

The NT counterpart to נֶ֫פֶשׁ is the Greek word ψυχή. Although the semantic range of ψυχή would expand in Greek literature to include “soul,” its initial and primary meaning is “life.”19 The translators responsible for the Septuagint render נֶ֫פֶשׁ as ψυχή in virtually every verse cited above, and New Testament translations of the Old Testament do so consistently (Matt 22:37; Acts 2:27; 1 Cor 15:45; Heb 10:38). This, “life,” appears to be the most common meaning of ψυχή in the New Testament (e.g., Matt 2:20; Mark 10:45; Luke 6:9; John 10:11; Acts 15:26; Rom 16:4; Rev 12:11).

* * *

To explore the various senses in which ψυχή is used in the New Testament, check out the Bible Word Study guide [Logos > Guides > Bible Word Study] in the Logos Bible app, enter the word ψυχή into the lookup field, and press Enter. Logos is available free for mobile, web, or desktop.

* * *

New Testament authors also use ψυχή in the other primary way in which Old Testament authors use נֶ֫פֶשׁ, namely to mean “person.” Luke records, for example, that “there were added that day about three thousand souls [ψυχή]” (Acts 2:41; cf. Acts 2:43; 7:14; 27:37; 1 Cor 15:45; 1 Pet 3:20). It, too, is used for one’s own person or self, as in, “my beloved with whom my soul [lit., my ψυχή] is well pleased” (Matt 12:18), and, “My soul [lit., my ψυχή] magnifies the Lord” (Luke 1:46).

Because it is both the New Testament Greek equivalent of the Old Testament נֶ֫פֶשׁ and a reference to an embodied person with emotional and spiritual needs and desires (and not only material ones), ψυχή lends itself to being used for one’s heart (figuratively) or mind, or to one’s entire being. Thus, Paul urges readers to be “bondservants of Christ, doing the will of God from the heart [ψυχή]” (Eph 6:6), and he hopes to find them “with one mind [ψυχή] striving side by side for the faith” (Phil 1:27). However, Johannes Louw and Eugene Nida explain that, in passages like these, “ψυχή refers really to the entire being of a person, so that … Eph 6:6 may be appropriately rendered as ‘but with your whole being, do what God wants, as slaves of Christ.’”20

There are no texts in the New Testament in which ψυχή clearly must mean “soul” as the non-physical substance of a person. Jesus says humans “kill the body but cannot kill the soul [ψυχή],” whereas God “can destroy both soul [ψυχή] and body in hell” (Matt 10:28), but ψυχή means “life” leading into (2:20; 6:25) and out of (10:39) this verse. Plausibly, Jesus is saying only God can ultimately end a person’s life. After all, he’ll later say that the fact Yahweh is God of the dead patriarchs and God “of the living” proves the patriarchs must one day live again (Matt 22:31–32). And in his apocalyptic vision, John sees “under the altar the souls [ψυχή] of those who had been slain” (Rev 6:9), but then they are given clothing to wear (v. 11), suggesting John is using “souls [ψυχή] of those” in the periphrastic sense of “them.” The dualist reading of such texts is reasonable, but not certain.

And breathe: “spirit” (נְשָׁמָה ,רוּחַ, πνεῦμα) as breath and mind

Biblical language thought to refer to the “spirit” of human beings is also present in the beginning, where it in fact names life-giving breath from God. In the Old Testament, “breath” in the phrase “breath of life” translates either נְשָׁמָה, as it does when God breathes it into Adam’s lifeless nostrils (Gen 2:7), or רוּחַ (e.g., Gen 6:17). These words “are treated as virtually the same” in this expression;21 and both are sometimes translated “spirit” when referring to humans (נְשָׁמָה in, e.g., Prov 20:27; רוּחַ in, e.g., Gen 41:8). This “breath of life” is enjoyed by all breathing creatures (Gen 6:17; 7:15, 22), and if God were to take it back, “all flesh would perish together, and man would return to dust” (Job 34:14). Thus, “‘breath of life’ is the life-sustaining principle embodied in man that comes from God,” and, “To possess the ‘breath of life’ or ‘breath’ is to be alive (e.g., Deut 20:16; Josh 10:40; Job 27:3); the absence of it describes the dead (1 Kgs 17:17).”22

Unlike a dead person (so far as can be discerned), a living person feels, thinks, and wills, so רוּחַ as life-principle gives rise to רוּחַ as psychospiritual-principle. Wolff explains, “The rise and fall of the breath is namely in the first place to be seen together with the movement of the feelings” and “attitudes of mind.”23 Thus, Ephraim’s men feel “anger [רוּחַ]” toward him (Judg 8:3; cf., 2 Chr 21:16; Eccl 10:4);24 and God says to Israel, “I know the things that come into your mind [רוּחַ]” (Ezek 11:5; cf., 1 Chr 28:12). The רוּחַ “comes later to mean simply the organ of our psychic life, what spirit ordinarily means today.”25 Hannah, despondent and desperate for a child, tells Eli the priest, “I am a woman troubled in spirit [רוּחַ]” (1 Sam 1:15). Again, none of this suggests רוּחַ must refer to a non-physical part of a human.

The New Testament counterpart to the Old Testament רוּחַ and נְשָׁמָה is πνεῦμα, which foundationally means “air in movement.”26 It can thus refer to a person’s breath, as in, “the breath of his mouth” (2 Thess 2:8; cf., Rev 11:11). This is what it appears to mean in some texts in which it is usually translated “spirit.” When Jesus commands a dead girl to rise, for example, “her spirit [πνεῦμα] returned, and she got up at once” (Luke 8:55); and James says, “the body apart from the spirit [πνεῦμα] is dead” (Jas 2:26).27 Considered in the light of Qohelet’s statement that, at a human’s death, “the breath [רוּחַ] returns to God who gave it” (Eccl 12:7, NRSV, LEB; πνεῦμα in the LXX), Jesus entrusting his πνεῦμα to his Father (Luke 23:46; cf., Acts 7:59) likely represents his trust that God, to whom his breath is about to return, will give it back in resurrection.

Like its Old Testament counterpart, πνεῦμα can by extension refer to the seat of one’s feelings and thoughts. Touched by the weeping of others, Jesus “was deeply moved in his spirit [πνεῦμα] and greatly troubled” (John 11:33). He says in the Beatitudes, “Blessed are the poor in spirit [πνεῦμα]” (Matt 5:3). And πνεῦμα can seemingly mean simply “mind,” as in, “who knows a person’s thoughts except the spirit [πνεῦμα] of that person, which is in him?” (1 Cor 2:11). Of course, it does not follow that such uses of πνεῦμα name a non-physical part of man unless one assumes, a priori, that a mind cannot be physical.

“Your whole spirit and soul and body”

The foregoing observations lend themselves to simple, straightforward physicalist interpretations of texts typically translated as though they include non-physical substances in lists of human parts. Though “the flesh is weak,” Jesus says, the mind/attitude (πνεῦμα) “is willing” (Mark 14:38). An unmarried person is better able to focus on “how to be holy in body” and mind/attitude (πνεῦμα; 1 Cor 7:34; cf., 2 Cor 7:1). Paul prays that the reader’s mind/attitude (πνεῦμα), life (ψυχή), “and body be kept blameless” (1 Thess 5:23). And God’s word metaphorically pierces every aspect of human being: life (ψυχή), mind/attitude (πνεῦμα), “joints” and “marrow” (Heb 4:12).

Christian physicalism faces some meaningful, interesting objections, but they are mostly philosophical, not exegetical. How can one’s mind fail to reduce to chemistry if it is emergent from functioning neurons? How can a resurrected human be meaningfully identical to the person who died if all matter constituting the body has been recycled and the resurrection body comprises entirely different matter? Christian physicalists continue to wrestle with these and other important questions. Their anthropology, however, certainly seems consistent with Scripture.

Further reading

- Wonderfully Made: A Protestant Theology of the Bible

- Created in God’s Image

- Sometimes Less Is Just Less: Contending for Dichotomy over Monism

Related resources

Body, Soul, and Life Everlasting: Biblical Anthropology and the Monism-Dualism Debate

Regular price: $21.99

New International Dictionary of Old Testament Theology and Exegesis | NIDOTTE (5 vols.)

Regular price: $159.99

Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament Based on Semantic Domains

Regular price: $27.99

A Greek–English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature, 3rd ed. (BDAG)

Regular price: $149.99

- The tumor was roughly the size of a chicken egg.

- The official diagnosis was Primary CNS (central nervous system) Lymphoma. After about a month and two rounds of chemotherapy, the tumor had shrunk to about the size of a lima bean, and my wife’s brain tissue was no longer visibly pushed aside by it.

- J. P. Moreland and William Lane Craig include qualia among the “features of consciousness,” calling it “phenomenal consciousness. Phenomenal properties (also called qualia [the plural of quale]) or phenomenal conscious states are such that there is a raw feel or a what-it-is-like to be in that state.” J. P. Moreland and William Lane Craig, Philosophical Foundations for a Christian Worldview, 2nd ed. (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press Academic, 2017), 213–14.

- Howard Robinson, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, s.v. “Dualism”; emphasis added. More precisely, this is substance dualism, so-called because the body on the one hand, and the soul and/or spirit on the other hand, represent two kinds of substance, i.e., two kinds of property-bearing concrete entities.

- The dichotomist dualist sees “soul” and “spirit” as essentially synonymous, referring equally to the same non-physical “part” of a human being. The trichotomist dualist sees “soul” and “spirit” as referring to two distinct non-physical “parts.” These are sometimes called bipartite and tripartite views, respectively, as in Jan A. Sigvartsen, Afterlife and Resurrection Beliefs in the Pseudepigrapha (New York: T&T Clark, 2019), 149. Technically, these are both forms of dualism, but “dualism” is sometimes reserved for the dichotomist or bipartite view. See, e.g., John W. Cooper, Body, Soul, and Life Everlasting: Biblical Anthropology and the Monism-Dualism Debate (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1989), 9.

- Cooper, Body, Soul, and Life Everlasting, 20; emphasis added. I have added “kind of” because the distinction between monism and dualism is in the number of kinds of substances, not the number of substances. The human body is in one sense a single physical substance, for example, but in other senses, every bone is a substance in itself, and every molecule that makes up every bone, and every atom comprising every molecule, etc. However, every such substance is physical. Idealism is another form of anthropological monism, according to which human beings are composed of only spiritual or non-physical substances.

- Physicalism, like dualism, is a family of views. Notwithstanding the word “dualism” in some of their accepted labels, these include (but are probably not limited to) nonreductive physicalism, emergent dualism, property dualism, and constitutionalism.

- Nancey Murphy, “Human Nature: Historical, Scientific, and Religious Issues,” Whatever Happened to the Soul? Scientific and Theological Portraits of Human Nature, ed. Warren S. Brown, Nancey Murphy, and H. Newton Malony (Minneapolis, MI: Fortress Press, 1998), 2.

- Even if emergent dualists, property dualists, constitutionalists, and others would distinguish their views from nonreductive physicalism, they are nevertheless physicalists and believe mental properties are not reducible to physical ones. Also, whether a Christian could, in principle, be a reductive physicalist, is beyond the scope of this article.

- Murphy, “Human Nature,” 25.

- Joshua Farris, Sometimes Less Is Just Less: Contending for Dichotomy over Monism

- Kenneth A. Mathews, Genesis 1—11:26, New American Commentary (Nashville, TN: Broadman & Holman, 1996), 197.

- H. Seebass, “נֶ֫פֶשׁ nep̱eš,” in Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament, ed. G. Johannes Botterweck, Helmer Ringgren, and Heinz-Josef Fabry, 15 vols., rev. ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1974–2006), 9:512.

- D. C. Fredericks, “נֶ֫פֶשׁ,” in New International Dictionary of Old Testament Theology and Exegesis, ed. Willem A. VanGemeren, 5 vols. (Grand Rapids, IL: Zondervan Publishing House, 1997), 3:133.

- Seebass, “נֶ֫פֶשׁ nep̱eš,” 9:512–3.

- William Dyrness, Themes in Old Testament Theology (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press Academic, 1977), 85.

- Dyrness, Themes, 85.

- Hans Walter Wolff, Anthropology of the Old Testament, trans. Margaret Kohl (Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press, 1974), 17.

- Albert Dihle, “ψυχή in the Greek World,” in Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, ed. Gerhard Kittel and Gerhard Friedrich, 9 vols. (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1964), 9:609–11.

- Johannes P. Louw and Eugene A. Nida, eds., Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament: Based on Semantic Domains, vol. 1: Introduction and Domains, 2nd ed. (New York: United Bible Societies, 1988), 321; emphasis added.

- Mathews, Genesis 1—11:26, 196.

- Mathews, Genesis 1—11:26, 196.

- Wolff, Anthropology of the Old Testament, 36–37.

- In Proverbs 14:29, רוּחַ is used in parallel with אַף, which much more commonly means “anger” (e.g., Gen 27:45).

- Dyrness, Themes, 86.

- Walter Bauer et. al., eds., A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature, 3rd ed. (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago, 2000), 166.

- The NLT reads, “the body is dead without breath.”