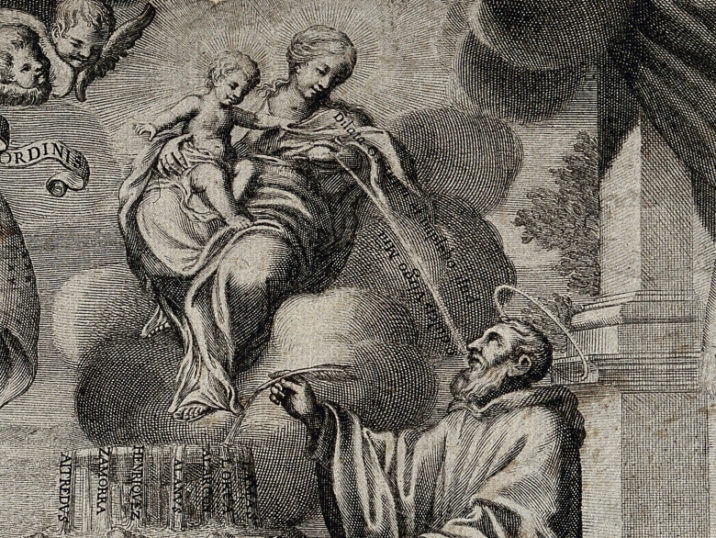

As a scholar of monasticism it seems to me that what roots biblical scholarship is rootedness in the text in such a way that it becomes one’s language of prayer and meditation. In this regard I would suggest that Bernard of Clairvaux (d. 1153) is a good model. Let me explain why.

In the twenty-first century it is most tempting to think of good biblical scholarship as rooted in the study of the original languages, a critical engagement with the original context and even a heavy dose of the Christian tradition’s way of interpreting the text, not to mention the heavy lifting of discerning the theological and canonical significance of the passage at hand. This all seems good. But although much of the above would have been quite foreign to Bernard of Clairvaux, I think he was a good biblical scholar and a worthy model for biblical scholarship today.

Bernard did not work in the original languages but was limited to the Latin Vulgate, itself a translation by Jerome in the fourth century. Yet Bernard took seriously the form of the Latin words and even the particular Latin words that were used in the Vulgate. At no point did he apologize for working with a translation. Perhaps we could say that he had such a high view of the perspicuity of Scripture that he was not overly bothered by the fact that he was not working in the original languages. This is not to diminish the necessity for the study of Hebrew and Greek but I do think that God can work through translations. Certainly the Holy Spirit is not limited to Hebrew and Greek verb tenses.

Thus, Bernard’s brilliance is not his use of so-called critical methods but in the fact that, as a monk, he had prayed, read and studied the Sacred Scriptures so intently that his vocabulary is literally a biblical vocabulary. Bernard’s words are imbued with the words of Scripture. Bernard’s thoughts are rooted in the biblical text. In his own sermons, he speaks in such a way that almost every sentence has an echo of the Bible. In this way, we know that Bernard was absolutely awash in the Bible. He was a good biblical scholar because he was wholly immersed in the Word of God. In the words of the great monastic scholar Jean Leclercq, Bernard’s biblical scholarship was rooted in meditative prayer and reminiscence:

“It is this deep impregnation with the words of Scripture that explains the extremely important phenomenon of reminiscence whereby the verbal echoes so excite the memory that a mere allusion will spontaneously evoke whole quotations and, in turn, a scriptural phrase will suggest quite naturally allusions elsewhere in the sacred books” (The Love of Learning and the Desire for God, p. 73).

Should we, as biblical scholars, be any less immersed than Bernard and the monastic tradition? Is not the sign of a good biblical scholar evidenced in her effusive biblical vocabulary? I would think that it is, and therefore, instead of reading the latest commentary (that can be done in due time) I would suggest we simply pray our way through the text, meditatively and with an eye to committing it to memory so that we can reminiscence about it when necessary. Bernard sets an example for us in this regard, and we would do well to follow his lead.

The Works of St. Bernard of Clairvaux is a 9-volume collection of the theologian’s letters and over 100 of his sermons, including substantial biographical information on the famous saint.

Get the Works in your Logos library today, and learn straight from his pen how a man saturated with Scripture writes, preaches, and lives.

]]>