The book of Revelation is the last in the Christian Bible and contains important information about the end times. Yet many Christians don’t feel equipped to read and study it or are scared to. That’s understandable—it’s full of wild imagery, confusing numbers, vague time references, strange visions, unseen realities, and unclear future events. Troublingly, Revelation indicates those to whom the author wrote the letter will undergo intense trials and difficulties.

Even so, the ending is a happy one. And it is filled with hope.

According to Paul, all Scripture—including the book of Revelation—is “breathed out by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness” (2 Tim 3:16). But there’s something unique about Revelation; according to its author, those who read and hear the words of the prophecy and “keep what is written in it” (Rev 1:3) will be blessed. It’s the one book in the Bible that will cause blessing somehow, so we would be wise to read it and study it.

We find some of the great topics of prophecy and their consummation in Revelation, such as the Church, the resurrection of the saints, the great tribulation, and the second coming of Christ. Yet as one prominent pastor writes, “The most prominent characteristic of the book of Revelation is that it is misunderstood.”

Keep reading to do a deeper dive into critical topics related to the book of Revelation—who wrote it and when, what apocalyptic literature means, who some of the key figures are like the mark of the beast and Gog and Magog, tips for studying Revelation, and more. You can start at the beginning and read to the end or jump to the topics that interest you.

- What the word “revelation” means

- Overview of the book of revelation: author, date of writing, audience, theme, etc.

- What is the millennium?

- Key figures in the book of Revelation: the mark of the beast, Gog and Magog, the number 666, etc.

- How the Logos Bible app can help you study Revelation further

- Approaches to interpreting the book of Revelation

- 6 quick tips for studying the book of Revelation

- 3 mistakes to avoid when reading and studying Revelation

- John’s use of the Old Testament in Revelation

- 18 allusions in the book of Revelation to the Old Testament

What does the word “revelation” mean?

Before unpacking details about the book of Revelation, we need to know what the word “revelation” means. Tyndale Bible Dictionary says it refers to either:

- the act of revealing for the purpose of making something known

- the thing that is revealed

In theology (the study of God), revelation refers to “God’s self-disclosure or manifesting of himself or things concerning himself and the world.”1 The Lexham Bible Dictionary (LBD) says the term “revelation” (Gr. apokalypsis) means “to expose in full view what was formerly hidden, veiled, or secret.”2

Think of a scratch-off game ticket, like a lottery ticket or the ones you get from a fast-food restaurant. You know there’s something underneath the silver coating—but until you scratch it off, you can’t see the “prize” that’s waiting (a free soda or a million dollars). In the case of biblical revelation, God is the one who unveils what’s hidden—in his time (Prov 25:2).

Overview of the book of Revelation

The following section is adapted from various entries in the Lexham Bible Dictionary.

***

Author

Author

The author of Revelation “identifies himself as John,3 a servant of God and spiritual brother to the members of the seven churches” (1:1, 4, 9; 22:8). John is further designated as a prophet (22:6, 9) who was residing on the island of Patmos in the eastern Aegean Sea, “because of the word of God and the testimony of Jesus” (1:9 NASB). Likely, his presence on Patmos was not for the purpose of proclaiming the word of God, but rather he had been exiled there as punishment by the state for preaching.4

Date of writing

Date of writing

Revelation may have been composed between AD 68–69 during the religious upheaval following the reign of the emperor Nero or around AD 95 during the reign of the emperor Domitian. The latter date has the support of Irenaeus5 and Eusebius.6 The earlier date was widely held in the nineteenth century, while the latter date gained appeal in the twentieth century. Today, the debate continues.7

Canonicity and acceptance of Revelation

Canonicity and acceptance of Revelation

By AD 200 Revelation was accepted as authoritative by several bishops and other Christian leaders in the Mediterranean world . . . However, some rejected Revelation as Scripture. Gaius and Dionysius of Alexandria argued that Revelation was not apostolic in origin. Even as late as the fourth century, Eusebius classified the document’s scriptural status as “disputed.” By 1300, Revelation was acknowledged as authoritative Scripture by most Christians.8 However, even today, there still exist some Christian communities who reject Revelation’s authority.

Original audience

Original audience

The book of Revelation is addressed to the seven churches of Asia Minor (present-day western Turkey). The first letter is directed to the church in Ephesus, the city closest to the island of Patmos. The remaining recipients of the letters are Smyrna, Sardis, Thyatira, Pergamum, Philadelphia, and Laodicea, which geographically form a loose circuit, thereby making it easy for a messenger to travel and deliver John’s document to the various churches.

Setting

Setting

Determining the historical and social conditions of those who received Revelation is difficult, primarily because the book is prophetic. For example, it is unclear if the persecution John is speaking about refers to the past (1:9; 2:13) or the future (2:10; 3:10) or both. Revelation 6:9 provides another example: John sees “the souls of those who had been slain because of the word of God and the testimony they had maintained” (6:9 NIV). This could refer to a past, present, or future suffering. Evidence within Revelation itself, and external sources, suggests that there were major economic, political, and social issues facing the seven churches in Asia Minor.

Economic situation

Evidence indicates there was pressure in the commercial arena for Christians to submit to pagan worship practices. For example, every craftsman and trader had the opportunity of belonging to his appropriate guild. These societies included sacrificing to a pagan deity (likely to the emperor as well) and participation in a common meal dedicated to a pagan deity.9 To survive in the international marketplace, it was essential to join trade guilds. It would have been a compromise of their faith for Christians to participate in the activities of these organizations. It is [possible that] the Nicolaitans [whose identity and teachings are not explained in Revelation] falsely “redefined apostolic teaching” so Christians could feel comfortable participating in these pagan organizations.10

Political situation

Christians in Asia Minor were experiencing harassment from their Jewish neighbors, but Judaism enjoyed privileged status under Roman rule.11 Ephesus, Pergamum, Sardis, and Laodicea each had Jewish communities. In the early years of the Church, Rome did not see a distinction between Christianity and Judaism. Later, though, Jewish enemies could act as informants to Rome against Christians. This scenario might explain the references to “the synagogue of Satan” in Revelation 2:9 and 3:9.12

Internal situation

The letters to the seven churches reveal that the communities were faced with strife within their communities. These problems were in the form of false prophets, whose teaching threatened to weaken community boundaries (Balaam, 2:14, the Nicolaitans, 2:6, 15, and Jezebel, 2:20).

Revelation was written during a time when some Christians saw it advantageous to assimilate with the culture. There was likely some local persecution but not widespread state persecution. Consequently, there was a tendency for complacency and a lack of desire and motivation to remain faithful.

Type of literature and style (genre)

Revelation cannot be categorized as being one style (or genre) of literature. The author employs various styles and techniques to communicate his message, including apocalyptic, prophetic, epistolary, and liturgical styles.

Apocalyptic style

The apocalyptic (Gr. apokalypsis) style of writing found in Revelation was used in both Jewish and Christian circles. It often has an angel or otherworldly being reveal heavenly mysteries to a human recipient. The mysteries are delivered in the form of visions placed in a narrative framework.13 The visions serve to interpret the difficult times the recipients are experiencing, portraying them as temporary and counterfeit, while the heavenly mysteries are portrayed as an accurate depiction of reality. In this function, apocalyptic literature has an ethical component. On the basis of the message, the recipients are mandated to modify their thinking and behavior. They are expected to either persevere or overcome depending on their current situation. Those who pursue a life of faithfulness and purity will avoid the punishments promised to the unfaithful.14

Prophetic style

Revelation is not only apocalyptic in form, but it is also prophetic. It is prophetic both by forthtelling (e.g., 1:8) and foretelling (see 1:19, “write . . . what will take place later”). Prophecy style is distinguished from apocalyptic by its more positive tone (repentance will forestall judgment) and its spoken nature (1:8; 22:12–13, 16, 20). Apocalyptic style tends to be more negative in tone (not much hope in the present, yet future vindication and judgment are certain), and it is more visionary in form.15

Epistolary style

In addition to Revelation having apocalyptic and prophetic elements, it also is a letter written to seven churches in Asia Minor. It possesses a typical epistolary greeting formula (1:4–5, “John to the seven churches . . . Grace and peace”), and the entire book climaxes in a brief postscript (22:21), which is characteristic of other New Testament letters.

Liturgical style

At least 17 instances of hymns or acclamations appear in the book of Revelation.16 Both biblical and extrabiblical evidence supports that hymns, liturgical dialogues, songs, and praises were used for worship and possibly even catechism.17 It would have been natural for the Church to appropriate the liturgy in Revelation for these purposes.

Narrative

Revelation also contains narrative elements. Examples of narrative components are:

- characters (e.g., the Lamb, the 24 elders),

- settings (e.g., Patmos, the heavenly throne room),

- plot (e.g., a cosmic struggle between good and evil)18

Symbolism

Revelation uses a great amount of highly symbolic language. Gregory Beale contends that “made it known” (NIV) in Revelation 1:1 is a rendering of the past tense of sēmainō, which can mean “to communicate by symbols.”19 The particular nuance of this word in 1:1 is confirmed by its parallelism with “show” in the first part of 1:1. The word “show” throughout Revelation always introduces communication by symbolic vision (4:1; 17:1; 21:9–10; 22:1, 6, 8).20 Therefore, John is not giving his audience photographs of heaven. Instead, he is communicating a message in symbols and metaphors. Consequently, the beast John encounters in Revelation represents a human force that opposes God rather than a literal creature.21

Literary structure

Situated between the letters to the seven churches and the presentation of a final triumph is a text full of recurring motifs (Rev 6–16: seven seals in 6:1–8:5, seven trumpets in 8:6–11:19, and seven bowls in chapters 15–16). In each of these scenes, a cataclysmic end-of-age event is presented and is followed by more visions. Does Revelation 6–16 portray a continuous chronological progression of events? Or does it render two or three repetitions of the same event with some variation?

Rather than considering Revelation to be a straightforward chronological progression, Bishop Victorinus of Pettau, in the late third century, proposed that each of the repeated end-of-history scenes portrayed parallel accounts of the same event. Each scene is merely a repetition or recapitulation of the same event but in another form. More recently, Adela Collins argued that it is a cycle of five visions (6:1–8:5; 8:2–11:19; 12:1–15:4; 15:1–16:21; 17:1–19:10; 19:11–21:8) that recapitulate.22 However many cycles one proposes, they all eventually move forward toward a final climax.

Explore resources on interpreting the book of Revelation.

The Book of Revelation (The New International Greek Testament Commentary | NIGTC)

Regular price: $64.99

The Book of Revelation (The New International Commentary on the New Testament | NICNT)

Regular price: $42.99

Revelation (Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament | BECNT)

Regular price: $59.99

***

What is the millennium?

Revelation has one of the most discussed passages in Revelation:

Then I saw an angel coming down from heaven, holding in his hand the key to the bottomless pit and a great chain. And he seized the dragon, that ancient serpent, who is the devil and Satan, and bound him for a thousand years, and threw him into the pit, and shut it and sealed it over him, so that he might not deceive the nations any longer, until the thousand years were ended. After that he must be released for a little while. (Rev 20:1–3, emphasis added)

According to the Lexham Bible Dictionary, Revelation 20:1–6 is “the only passage that mentions a time period of 1,000 years” and presents an era when “Satan is heavily restricted and unable to mislead the nations.”

Verses 4–6 say that at this time, God will resurrect the saints to reign with Christ: “The millennium seems to occur before the creation of a new heavens and new earth (Rev 21:1–2)” and “displays God’s victorious reign over evil and the fulfillment of his promises to his people.”23

Various views on the nature of the millennium exist. Below, Craig Keener, Professor of New Testament at Asbury Theological Seminary, helps unpack each:

Key figures in the book of Revelation

The antichrist

The antichrist is a figure empowered by Satan who functions as an enemy of Jesus Christ and the Church. In the context of apocalyptic literature, this figure performs false miracles, deceives many to discourage people from worshiping the true God, and persecutes God’s people.

The term “antichrist” could mean either “against Christ” or “in place of Christ.” While the actual term “antichrist,” which originates in the New Testament, appears infrequently in Scripture, the concept of the antichrist appears numerous times in the New Testament. Because the broader concept appears more often than the specific term, multiple perspectives have been presented on “antichrist,” leading to the understanding that the better phrase used to discuss the issue may be “eschatological antagonist.”

Where in Scripture does the word ‘antichrist’ appear?

Johannine literature

The term “antichrist” appears in Scripture four times, solely in the Johannine corpus (1 John 2:18, 22; 4:3; 2 John 1:7). First and Second John combat heresies and discuss the preservation of true doctrine. The Letters indicate a heresy was spreading throughout the community that denied “Jesus is the Christ” (1 John 2:22) and his “coming in the flesh” (2 John 1:7).

The first time John uses the term, he reminds his readers that they have heard about an antichrist coming (1 John 2:18). This reveals that teaching concerning this figure precedes John’s use of the term. He uses the term in his letters to describe those who oppose these central doctrines concerning the person of Jesus Christ. For John, those who had received the truth yet teach false doctrine concerning Jesus are antichrists.

The Synoptic Gospels

The Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) present the concept of antichrist in a discourse by Jesus, in which he warns his disciples concerning things to come. All three of these Gospels provide warnings against following those who come proclaiming to be the Christ (Matt 24:4–5; Mark 13:5–6; Luke 21:8). Mark notes the rise of “false Christs and false prophets” who possess the power to perform “signs and wonders” to deceive people and legitimate their claims as messianic figures (Matt 24:24; Mark 13:22). The description of these “false Christs” parallels the description appearing in the Pauline text, indicating that the term “false Christ” functions as an equivalent term to “antichrist.

Pauline Epistles

Second Thessalonians provides the earliest written New Testament statements concerning the antichrist concept (accepting that Paul’s writings are among the earliest in the New Testament). Paul combines two antichrist traditions—the political and the religious. He writes to the Thessalonians to correct their misunderstanding that the Day of the Lord has occurred, explaining that specific events must occur prior to the Day of the Lord—namely, rebellion and the revelation of an eschatological antagonist.

Paul refers to the figure as “the man of lawlessness” and “the son of destruction,” a Semitic idiom describing one who is destined for destruction; 2 Thess 2:3. Paul connects the revealing of this figure to his leading a coming rebellion (2 Thess 2:3). He then notes this figure’s actions, stating he will proclaim himself as God and desire to be worshiped. Like the false christs and false prophets mentioned in Matthew and Mark, this one will display his power by “signs and wonders” to deceive people (2 Thess 2:9–10). Paul also notes that Jesus himself will destroy this antagonist (2 Thess 2:8).

Revelation

The canonical work receiving the most treatment concerning the topic of antichrist is the book of Revelation. Unlike other New Testament writings, this work does not use a human as its antichrist image—it uses two “beasts”:

- A beast from the sea, which represents the political antichrist tradition; it wears 10 crowns and receives the dragon’s power, throne, and authority (Rev 13:2).

- A beast from the land, which represents the religious antichrist tradition; it exercises the authority of the first beast, and like those of whom Jesus spoke, uses its power to perform “signs” and deceive the people, directing them to worship the first beast (Rev 13:13–14).

John later refers to the second beast as the “false prophet” (Rev 16:13; 19:20), a reference that echoes Jesus’ statements in the Synoptic Gospels and John’s statements in 1 John. This label also recalls Deuteronomy 13, where God provides instructions concerning false prophets. As with Paul’s writings, John also notes the ultimate destruction of both beasts—they are captured and cast into the lake of fire (Rev 19:20).

Bible passages that reference or allude to the antichrist:

- Daniel 7:24–27

- Daniel 8:23–25

- Matthew 24:24

- Luke 21:8

- 2 Thessalonians 2:3–12

- 1 John 2:18–22

- 2 John 7

- Revelation 13:1–14

The mark of the beast

The mark of the beast is “a sign” (Rev 16:2; 13:16; 19:20) to identify those who worship the beast “of the sea” (Rev 13:1). It is used in contrast to the “seal” of those who follow Christ, the Lamb, into the new creation (Rev 7:3; 14:1).24

John calls for the person with wisdom and insight to “calculate the number of the beast” (Rev 13:18). The exact meaning behind the “mark of the beast” is difficult to fully understand in its historical context. Its biblical roots can be traced through the Greek translations of Isaiah 44:5, Ezekiel 9:3–11, and Psalms of Solomon 15:9, where it may also be used to convey an eschatological reality that God both owns and protects his people.25

4 common interpretations of ‘mark’ in the ‘mark of the beast’26

- “Mark” could refer to insubordinate slaves and captured soldiers being tattooed or branded on the arm with such things as an owl, a galloping horse, or an ivy leaf, or inscribed with their new master’s seal. 27The essence of such a mark is proof of property, ultimately connected to Roman worship practices.28 A similar kind of mark, typically in the form of a tattoo, could be given to those who willingly worshiped a particular Roman deity. This type of mark is well-documented in first-century writings and relics.29Such a mark may have expressed open loyalty and devotion to the deity.30

- “Mark” could refer to imperial seals that bore the image and name of a Roman emperor. Here “mark” would imply a technical legal understanding of the word. There is evidence to suggest that such seals were used to verify the buying and selling of property.31 Most surviving documents of this type were commercial in nature and approved by the emperor himself.32 A similar imperial seal was also used in certificates issued to faithful worshipers of the imperial image.33

- “Mark” could refer to Roman coins, which also bore the image and name of a Roman emperor. Roman coins were used in both public and private commerce, meaning the “mark” was widespread throughout the Roman Empire.34

- “Mark” could refer to the Jewish practice of wearing phylacteries, which were small leather boxes that held various portions of Scripture and were worn on the hand and forehead.35

Use of the mark of the beast in Revelation 13:16

While each of these four uses of “mark” conveys certain historical understandings commonly held in the first century AD, none of them individually offers a satisfactory explanation for the use in Revelation 13:16.36 The reasons for this are:

- A “mark” given on the forehead of insubordinate slaves, captured soldiers, or devoted worshipers of a particular Roman deity would have been considered a “branding” and a sign of disgrace more than a sign of loyalty.

- Imperial seals used in legal matters or in Roman worship centers were meant for technical imperial records and not for public, commercial usage.

- The “mark” in Revelation 13:16 is associated with a person’s right hand or forehead, not a Roman coin.

- Jewish phylacteries were typically worn on the left arm rather than the right.37

Some scholars conclude that the historical ambiguity of the word “mark” suggests a primarily eschatological function. If the “mark of the beast” was not an issue in the first-century Church, it was likely discussed as a warning for the near future for the early Church.38

The mark is also interpreted as a contextual parallel to the seal on the foreheads of those who worship the Lamb:39

Then I saw thrones, and seated on them were those to whom the authority to judge was committed. Also I saw the souls of those who had been beheaded for the testimony of Jesus and for the word of God, and those who had not worshiped the beast or its image and had not received its mark on their foreheads or their hands. They came to life and reigned with Christ for a thousand years. (Rev 20:4)

Historically, the mark has been interpreted in tandem with “calculating” the number of the beast as John challenges readers to do in Revelation 13:18.40 Many modern scholars interpret the mark of the beast through the eyes of the intended readers, finding the most likely interpretation in the historical setting of Roman imperial religion and the figure of Nero.41

Bible passages that reference or allude to the ‘mark of the beast’:

- Ezekiel 9:3–11

- Revelation 13:15–14:1

- Revelation 20:4

Gog and Magog

Magog is a nation that Ezekiel prophesies against—specifically against its leader, Gog (Ezek 38:1–6). Magog appears again in the book of Revelation as a nation allied with Satan (Rev 20:8). Gog is a name mentioned in Ezekiel’s prophecies as the leader of the hordes from the north who will descend on Israel (Ezek 38:2–18; 39:1–11). This power from the north, “Gog of Magog,” appears as two nations, “Gog and Magog,” who fight for Satan in Rev 20:8. (Read more about what Gog and Magog may represent below.)

Gog and Magog in Ezekiel

Ezekiel’s identification of Gog appears to be connected with the table of nations in Genesis 10, as he associates Gog with Magog, Meshech, Tubal, and Gomer, all sons of Japheth. The description of Gog as an invading power follows standard prophetic themes, with multiple allusions to Isaiah (compare Ezek 38:8 with Isa 2:2–4; Ezek 38:10–12 with Isa 10:6). The notion that Yahweh will incite Gog to attack the people of Israel in service to his purposes—and later turn against the invader in wrath—is rooted in Isaiah’s theology of dual-agency (Isa 10:12).

Ezekiel may have been influenced by prophetic descriptions of an “enemy from the north” (Jer 1:13–15, 4:6) and perhaps has connected this prophecy with Gyges of Lydia, a renowned king from Anatolia. The cosmic disruption described in Ezekiel 38:19–23 is rooted in the “Day of the Lord” prophetic tradition, in which God appears as warrior, judge, and King to defeat his enemies (e.g., Joel 2).

***

Who might Gog and Magog represent?

God has given us many details regarding the end times, but not every detail. Gog and Magog are one such elusive subject. Theologians have long tried to identify this person and location.

While there has been speculation that Gog and Magog represent modern countries, today’s readers must bear in mind that the Bible was written not to give us all the answers to factual questions but to prepare Christians for the eschatological future.

Ultimately, only God knows—but here are three quotes from prominent theologians to get your interpretive juices flowing.

Just as it represented the composite nations who were to attack God’s people at the end of the great tribulation that begins Armageddon, here it seems likely that [Gog] is referring to all of the people who will attack God’s true people with the same hateful vigor at the end of the thousand-year reign of Christ when Satan is let loose from the abyss.

—Edward Andrews, Ezekiel, Daniel, & Revelation: Gog of the Land of Magog, Kings of the North and South, & the Eight Kings of Revelation

Gog is depicted as the “prince” who is over “Rosh” (rosh is also rendered as “chief prince” in the NIV), Meshech, and Tubal. There is no little amount of ink spilled over the identity of “Rosh” as well, for it has often been equated with the name of “Russia,” a name from northern Viking derivation for the region of the Ukraine in the Middle Ages. Some have attempted to equate “Rosh” with the names of Rashu/Reshu/Arashi in neo-Assyrian annals. Others attempt to link “Rosh” with “Rus,” a Scythian tribe inhabiting the northern Taurus Mountains according to Byzantine and Arabic writings. The Scythians were those who were spread over some of the republics of the former Soviet Union, especially those in central Asia. The identity of “Rosh” must remain open, for the evidence is far from conclusive.

—Walter Kaiser Jr. Preaching and Teaching the Last Things: Old Testament Eschatology for the Life of the Church

Both Satan and the false prophet are portrayed in Revelation as deceivers (12:9; 20:3; 13:14; 19:20). It comes as no surprise that upon Satan’s release from the Abyss he returns to his nefarious activity. It is probable that the second infinitive clause in v. 8 builds upon the first (rather than being parallel),42 so that the verse says that Satan shall come forth to deceive the nations for the purpose of gathering them for battle. The nations that fall prey to Satan’s propaganda are said to be in “the four corners of the earth.”

This figure of speech is not intended to stress some ancient cosmology but to emphasize universality (cf. Isa 11:12; Ezek 7:2; Rev 7:1). The nations are further identified as Gog and Magog. In Gen 10:2 Magog is listed as one of the sons of Japheth. In Ezek 38:2 Gog is the chief prince of Meshech and Tubal,43who leads the invasion against Israel. Magog, according to Ezek 39:2, is a territory located in “the far north.” In Revelation, however, both Gog and Magog are symbolic figures representing the nations of the world that band together for a final assault upon God and his people.44 No specific geographical designations are intended. They are simply hostile nations from all across the world.

—Robert H. Mounce, Revelation, New International Commentary on the New Testament

The number 666 in Revelation

The below is excerpted from the entry “The Number 666” from the Lexham Bible Dictionary.

The number 666 is the number associated with the beast of Revelation 13 and is also known as the “mark of the beast.”

John’s apocalypse

The only biblical reference to the number 666 appears in Revelation 13:18:

This calls for wisdom: let the one who has understanding calculate the number of the beast, for it is the number of a man, and his number is 666.

The author of Revelation indicates that those who do not worship the beast will be put to death and that those who do not receive his number as a mark on their hand or forehead will not be able to buy or sell (Rev 13:16–17).

Interpretation of 666

Interpreters typically regard the number in Revelation 13:18 either as a symbol or as a reference to an actual historical figure—whether past, present, or future.

Symbolic view of 666

The symbolic view holds that the number 666 is representative of fallen humanity. Advocates of this view note that the number six falls one short of the perfect number, seven, and suggest that the triple six is a parody of the Trinity. Thus, the number symbolizes the antithesis of the perfection of the Godhead.45 Smalley states, “John is not referring here in the first place to individual and historical tyrants; he is speaking of varied types of authority [that] use power wrongly, so as to induce doctrinal error and ethical compromise.”46

Historical view of 666

The historical view holds that Revelation 13:18 refers to an actual historical figure. The most common historical view proposes that the number of the beast points to a historical person via an ancient mathematical code called gematria, which assigns a numerical value to each letter of the alphabet. Thus, in Greek, alpha = 1, beta = 2, gamma = 3, and so on. Likewise in Hebrew, aleph = 1, bet = 2, gimmel = 3, etc.

Irenaeus was one of the earliest interpreters to use this method to calculate the number of the beast, and he came up with the name Lateinos. One clear example of gematria is found in the Sibylline Oracles, where the name of Jesus is said to equal 888.47 Two of the most common conclusions based on gematria are that 666 refers to the emperor Nero or the emperor Domitian.48

Key Bible passage that references the number 666

- Revelation 13:16–18

***

How the Logos Bible app can help you study Revelation further

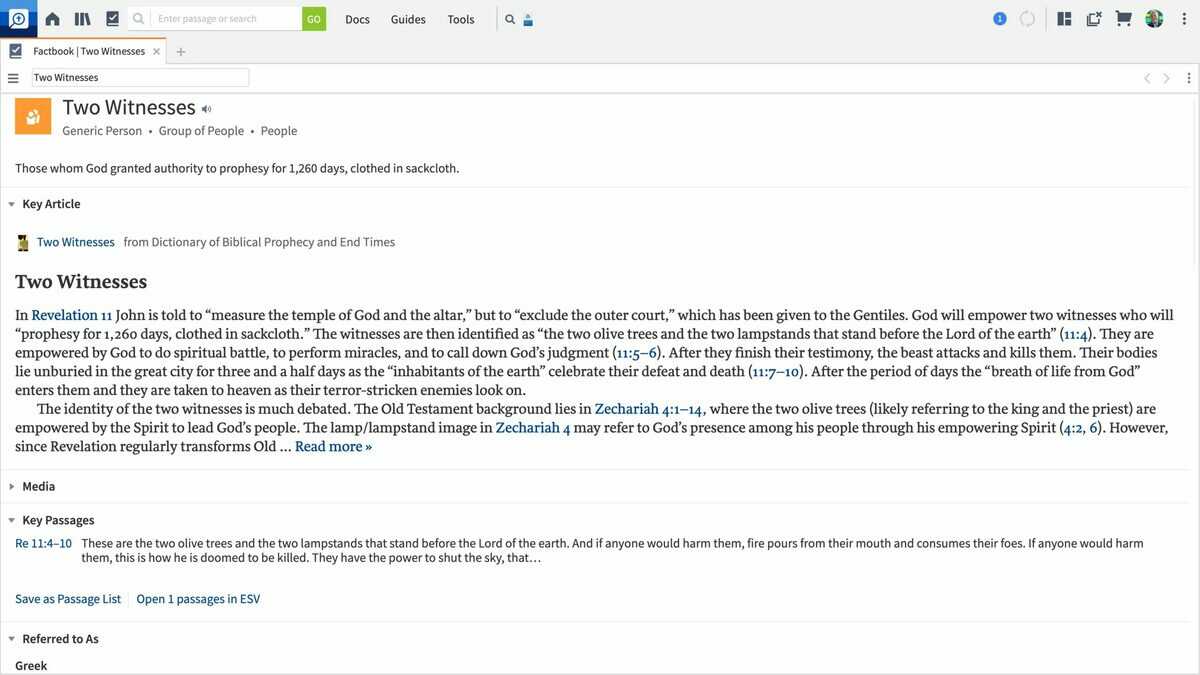

There are many other intriguing figures in Revelation, like the Lamb, the 144,000, the two witnesses, the 24 elders, the seven spirits, a slain lamb, a sovereign lion, a great red dragon, 10 kings, a bloody harlot, the beast, and the false prophet.

One easy way to explore each of these figures is with the Factbook in the Logos Bible app (available in Logos Starter and up). You can search for characters or even books of the Bible, significant historical events, important themes, theological concepts, and more. For example, a quick search for “Two Witnesses” reveals a key dictionary article, allusions in Old Testament Scripture, key passages, and other resources with helpful information:

Watch how the Factbook works:

See how the Logos Bible app can help you in your study of Revelation, eschatology, and more.

Approaches to interpreting the book of Revelation

Throughout Church history, Revelation has been interpreted through several different perspectives: non-historical, futuristic (or end-historical), church-historical, and contemporary historical.

Non-historical

The non-historical approach to understanding Revelation is also called poetic, idealist, or spiritual. This method is similar to the allegorizing approaches the Alexandrians (like Clement and Origen) used with the Bible. Read from this perspective, Revelation contains timeless general principles with no concern for the issues facing the seven churches. In its most extreme view, it denies any historical or future meaning of the book. In general, the symbols and images do not refer to any events in past or future church history.

Futuristic or end-historical

The futuristic or end-historical interpretation understands everything that follows Revelation 3 as events that have not yet occurred. According to this view, the visions given to John predict in detail two future periods of human history. The first period would fall seven years prior to Christ’s return (Rev 6:1–19:21). The second period would be the thousand years following the second coming of Christ (Rev 20:1–22:6).

Church-historical

Read from the church-historical viewpoint, Revelation is a detailed map of history from the time it was written until Christ’s return. Chapters 2 and 3 speak to John’s time, but typically the focus of this interpretation is the interpreter’s time, which is usually asserted at the end of history, close to the return of Christ.

Contemporary-historical

The contemporary-historical reading understands the book the way the original audience in the seven churches would have read it. Revelation is related to what happened during the time of the author; the main contents of chapters 4–22 are viewed as describing events of John’s own time.

Explore commentaries and courses on books related to Revelation.

Jesus, the Temple and the Coming Son of Man: A Commentary on Mark 13

Regular price: $16.99

Revelation through Old Testament Eyes: A Background and Application Commentary (Through Old Testament Eyes)

Regular price: $29.99

The Book of Ezekiel, 2 vols. (The New International Commentary on the Old Testament | NICOT)

Regular price: $90.99

6 quick tips for studying the book of revelation

1. Consult an outline of Revelation.

Studying Revelation is a big task, so don’t hesitate to learn as much as you can about the book before you start. Best first step? Read an outline. Or five. Exploring various outlines for the book of Revelation will give you a birdseye view of some of the main characters and events before you dive in; it will help get your brain around how Revelation is organized and the overarching theme for each chapter. Plenty of excellent outlines for Revelation available in commentaries and online—but here’s a simple one from the Lexham Bible Dictionary:

1:9–20 – The call of the prophet by the First and Last, the Living One who holds the keys of death and Hades

2:1–3:22 – Letters to the seven churches

4:1–5:14 – The vision of God and the Lamb

6:1–8:1 – Opening of the seven seals

8:2–11:19 – Seven trumpets

12:1–14:20 – Visions of the dragon, the beasts, and the Lamb

15:1–16:21 – Seven plagues and seven bowls

17:1–19:10 – Judgment of Babylon and the harlot

19:11–21:8 – Transition from Babylon to the New Jerusalem

21:9–22:5 – The New Jerusalem and the bride

22:6–21 – Epilogue49

2. Scour commentaries (from all views).

Many people over the centuries have put in the hard work of studying Revelation, and there’s much we can learn from their studies. That’s where commentaries come in. But be aware that they represent a range of eschatological (end times) views: some will take a historic premillennial perspective; others will be clearly amillennial. Regardless of which camp you fall in, as Craig Keener says, even the views you disagree with can be a great learning tool: “You can better understand where they’re coming from and . . . why we all hold the different views that we hold and can work together as members of one body in Christ.”50

(See how the Passage Guide in the Logos Bible app makes it easy to comb through multiple commentaries on Revelation—in minutes.)

3. Consider the central themes.

As Keener says, “End-time debates aside, Revelation is a very practical book.” In his course on Revelation, he notes several themes relevant to studying this apocalyptic book, regardless of which end-time view you embrace:

4. Let Scripture interpret Scripture.

Because Revelation is filled with symbolic imagery, we must also look at other places in the Bible that use similar imagery to help us understand what John was communicating. Allowing Scripture to interpret Scripture is known as hermeneutics—the art of interpretation. Revelation draws much of its imagery from elsewhere in the Bible, so reading other passages can shed light on confusing ideas. (See 15 examples below.)

5. Consider the genre.

You can also study up on Revelation’s literary type (or genre) before digging in—mainly because Revelation is probably the most nebulous book of the Bible. Neglecting to do so will undoubtedly lead to misinterpretation, mainly because it’s a mixture of four genres: apocalyptic, prophetic (1:3; 22:10), epistolary, and liturgical. (Head back to the beginning of this article to explore each genre further.)

6. Read (and interpret) responsibly.

The more layers to Revelation you peel away, the more you discover, which leads to even more things to study. But it also cracks open the door of possibility for questionable interpretation. Responsible Bible students will approach Revelation wisely and carefully (and not through the lens of modern-day news sources). They will guard against impressing their end-times view on the text to be correct—or make it “play nicely” with other passages in the Bible—and read it to discover what John meant when he wrote it.

More than anything, strive to come away with a God’s-eye view of the book of Revelation, not your own.

3 mistakes to avoid when reading and studying Revelation

This section leans heavily on David deSilva’s Unholy Allegiances: Heeding Revelation’s Warning.

***

Mistake #1: Reading Revelation as if it is all about us

Though Revelation will personally impact anyone who reads and studies it, it will speak most clearly, according to David deSilva in his book Unholy Allegiances: Heeding Revelation’s Warning, when read as a pastoral letter to the churches John cared about. DeSilva writes that Revelation was a word meant to “shape their perceptions of their everyday realities and to motivate faithful responses to their circumstances.”51

Mistake #2: Reading Revelation as if it is all about our future

By “prophecy,” deSilva says John might mean one of two things: he’s communicating predictions about events that will happen in his first audiences’ future, and “[John’s] predictions are the interpretative key to the book.” Or we can read it as God declaring his action in the present.

However, deSilva says typically when a biblical prophet speaks of the future, they usually limit the prediction to what’s immediately forthcoming, not the distant future: “Yet forty days, and Nineveh will be destroyed”; “There will not be dew nor rain for the next three years”; and the like.

“John remains within this range,” says deSilva, and this is seen in the author’s emphasis on the “imminence” of the confrontations and events he narrates, his conviction that he speaks about “what must soon come to pass” (Rev 22:6; cf. 1:3, 19; 4:1; 22:7, 10, 12, 20).52

Mistake #3: Reading Revelation as a mysterious code, one that we’re in a better position to unlock than anyone else

“From the very first word of his book,” writes deSilva, “John identifies his work as an ‘unveiling,’ not a ‘cryptic encoding’”:

Revelation was not sent to those seven churches as a mysterious text needing to be interpreted: it was sent to interpret the world of those readers. The first readers and hearers did not need a special “key” to unlock Revelation; Revelation was the key by which they could unlock the real meaning of what was going on around them, and so respond to it faithfully. Revelation “lifted the veil” from prominent features and persons in the audience’s landscape so that those Christians could see things in their world as they “really were” in light of the bigger picture of God’s purposes for the world, and the larger picture of the great revolt against God, which God would ultimately crush.

Like similar “apocalypses” written in the centuries around the turn of the era, Revelation pulls back the curtain on the larger landscape in terms of heavenly and infernal spaces and personnel and in terms of “how we got here” and “where things are heading,” so as to put the seven churches’ present realities within the interpretive context of a larger, invisible world and a sacred history of God’s activity and carefully defined plan.

The gift of the genre is to illuminate the moment for the ancient audience: it puts their mundane reality, along with its challenges and options, in its “true” light and proper perspective, so that the faithful responses become evident and advantageous.53

How then should we read and study Revelation?

DeSilva encourages reading Revelation as pastoral letter, early Christian prophecy, and apocalypse and says that doing so will “orient us toward Revelation in a different way from those who read it as a road map for our future or as a countdown to the end.”

Plus, it’s how we read the rest of Scripture. Ultimately, deSilva says reading Revelation through these lenses “enables us to move closer to seeing our world from God’s point of view” and, therefore, “to knowing how to respond to its challenges and entanglements in a way that reflects more closely our primary allegiance to the ‘kingdom of our Lord and of his Christ.”54

***

Dig deeper into resources on Revelation,

eschatology, and more.

John’s use of the Old Testament in Revelation

John borrows heavily from the Old Testament to communicate his message. While there is not one direct quotation from the Hebrew Scriptures, there may be as many as 400 allusions and echoes. John alludes to 27 different verses in Daniel alone.55 Over half of the references in the book of Revelation come from books like Daniel, Ezekiel, Psalms, and Isaiah.

Here are just 18—click each reference to show the passage and the Old Testament connection.

18 allusions in the book of Revelation to the Old Testament

Revelation 1:1–3 – last days

The revelation of Jesus Christ, which God gave him to show to his servants the things that must soon take place. He made it known by sending his angel to his servant John, who bore witness to the word of God and to the testimony of Jesus Christ, even to all that he saw. Blessed is the one who reads aloud the words of this prophecy, and blessed are those who hear, and who keep what is written in it, for the time is near.

Old Testament connection: Daniel 2:28–30; 45–47

Revelation 1:4, 20 – seven lamps

To the seven churches that are in Asia: Grace to you and peace from him who is and who was and who is to come, and from the seven spirits who are before his throne . . . As for the mystery of the seven stars that you saw in my right hand, and the seven golden lampstands, the seven stars are the angels of the seven churches, and the seven lampstands are the seven churches. (See also Rev 5:5–6)

Old Testament connection: Zechariah 4:2–7

Revelation 1:7 – coming with the clouds of heaven

Behold, he is coming with the clouds, and every eye will see him, even those who pierced him, and all tribes of the earth will wail on account of him.

Old Testament connection: Daniel 7:13

Revelation 1:15 – voice like the sound of rushing water

His feet were like burnished bronze, refined in a furnace, and his voice was like the roar of many waters.

Old Testament connection: Ezekiel 1:24; 43:2

Revelation 4:7 – lion, ox, man, and eagle

The first living creature, like a lion, the second living creature, like an ox, the third living creature, with the face of a man, and the fourth living creature like an eagle in flight.

Old Testament connection: Ezekiel 1:10; 10:14

Revelation 5:6 – slain lamb

And between the throne and the four living creatures and among the elders I saw a Lamb standing, as though it had been slain, with seven horns and with seven eyes, which are the seven spirits of God sent out into all the earth.

Old Testament connection: Exodus 12:6; Isaiah 53:7

Revelation 6:2 – white horse

And I looked, and behold, a white horse! And its rider had a bow, and a crown was given to him, and he came out conquering, and to conquer.

Old Testament connection: Zechariah 1:8; 6:3

Revelation 8:5–6 – thunder and lightning

Then the angel took the censer and filled it with fire from the altar and threw it on the earth, and there were peals of thunder, rumblings, flashes of lightning, and an earthquake.

Old Testament connection: Exodus 19:13–16; 20:18

Revelation 9:1 – star fallen from heaven

And the fifth angel blew his trumpet, and I saw a star fallen from heaven to earth, and he was given the key to the shaft of the bottomless pit.

Old Testament connection: Isaiah 14:12–14

Revelation 10:8–10 – eating the scroll (words)

Then the voice that I had heard from heaven spoke to me again, saying, “Go, take the scroll that is open in the hand of the angel who is standing on the sea and on the land.” So I went to the angel and told him to give me the little scroll. And he said to me, “Take and eat it; it will make your stomach bitter, but in your mouth it will be sweet as honey.” And I took the little scroll from the hand of the angel and ate it. It was sweet as honey in my mouth, but when I had eaten it my stomach was made bitter.

Old Testament connection: Jeremiah 15:16; Ezekiel 2:8–10

Revelation 12:1 – woman, sun, moon, and stars

And a great sign appeared in heaven: a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars.

Old Testament connection: Genesis 37:9–11

Revelation 14:14–16 – harvest

Then I looked, and behold, a white cloud, and seated on the cloud one like a son of man, with a golden crown on his head, and a sharp sickle in his hand. And another angel came out of the temple, calling with a loud voice to him who sat on the cloud, “Put in your sickle, and reap, for the hour to reap has come, for the harvest of the earth is fully ripe.” So he who sat on the cloud swung his sickle across the earth, and the earth was reaped. (See also vv. 17–18)

Old Testament connection: Joel 3:13

Revelation 15:5–6 – tabernacle

After this I looked, and I saw in heaven the temple—that is, the tabernacle of the covenant law—and it was opened. Out of the temple came the seven angels with the seven plagues. (NIV)

Old Testament connection: Exodus 38:21

Revelation 16:12 – dried-up river

The sixth angel poured out his bowl on the great river Euphrates, and its water was dried up to prepare the way for the kings from the East.

Old Testament connection: Isaiah 11:15–16; Jeremiah 51:36

Revelation 18:1–2 – Fallen Babylon

After this I saw another angel coming down from heaven. He had great authority, and the earth was illuminated by his splendor. With a mighty voice he shouted: “‘Fallen! Fallen is Babylon the Great!’ She has become a dwelling for demons and a haunt for every impure spirit, a haunt for every unclean bird, a haunt for every unclean and detestable animal. For all the nations have drunk the maddening wine of her adulteries. The kings of the earth committed adultery with her, and the merchants of the earth grew rich from her excessive luxuries.

Old Testament connection: Isaiah 21:9; Jeremiah 50:30; 51:7, 37

Revelation 19:15 – winepress

From his mouth comes a sharp sword with which to strike down the nations, and he will rule them with a rod of iron. He will tread the winepress of the fury of the wrath of God the Almighty.

Old Testament connection: Isaiah 63:1–6

Revelation 21:1 – sea (deep waters)

Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and the sea was no more.

Old Testament connection: Genesis 1:2; Daniel 7:3

Revelation 22:5 – eternal light

And night will be no more. They will need no light of lamp or sun, for the Lord God will be their light, and they will reign forever and ever.

Old Testament connection: Isaiah 60:1; Zechariah 14:7

See how the Logos Bible app can help you better interpret Revelation and other books of the Bible.

- Philip Comfort and Walter A. Elwell, Tyndale Bible Dictionary (Tyndale House Publishers, Carole Stream, IL), 2001.

- John D. Barry, “Book of Revelation,” Lexham Bible Dictionary (Lexham Press, Bellingham, WA), 2016.

- A former fisherman and disciple of John the Baptist, John is James’ brother, Jesus’ apostle, and the author of five New Testament books.

- The phrase “because of” is always used in Revelation for the result of an action and not to designate a purpose for an action (Boring, Revelation, 82). The Church historian Eusebius claimed John had been deported to the island of Patmos during emperor Domitian’s reign (Ecclesiastical History 3:18–20).

- Adversus Haereses, 5.30.3.

- Ecclesiastical History, 3.18.1; 3.20.9; 3.23.1.

- E.g., Mark Wilson, “The Early Christians in Ephesus and the Date of Revelation, Again,” Neotestamenica 39 (2005): 163–93.

- Talbert, The Apocalypse: A Reading of the Revelation of John (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 1994), 1.

- Kraybill, Imperial Cult, 196.

- G. K. Beale, The Book of Revelation (Eerdmans, 1999), 30.

- Josephus cites a long list of privileges extended to Diaspora Jews. Josephus, Antiquities, 16.6.2.

- David DeSilva, “The Social Setting of the Revelation to John: Conflicts within, Fears without.” Westminster Theological Journal 54 (1992), 279.

- John J. Collins, “Introduction: Towards the Morphology of a Genre.” Semeia Journal 14 (1979), 9.

- David Aune, Revelation: Word Biblical Commentary, 90–91.

- Grant R. Osborne, “Recent Trends in the Study of the Apocalypse,” pages 473–504 in The Face of New Testament Studies: A Survey of Recent Research. Edited by Scot McKnight and Grant R. Osborne (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2004), 477.

- Revelation 1:4–7; 4:8; 4:11; 11:17–18; 5:9–10; 5:12, 13; 7:12; 7:10; 19:1–3; 11:15; 12:10–12; 19:5; 15:3–4, 6–8.

- Pliny the Younger, Letters 10.96; Eph 5:19; Col 3:16.

- David Barr, Tales of the End: A Narrative Commentary on the Book of Revelation (Santa Rosa: Polebridge, 1998), 13.

- Beale, Revelation, 49–55.

- Beale, Revelation, 52.

- It is also noteworthy that in antiquity, even numbers were symbolic. The number seven symbolized perfection. Careful consideration should be given to what each symbol represents. It is possible that the author intended a symbol to have multiple points of comparison.

- The Combat Myth, 32–34.

- Barry, Lexham Bible Dictionary, “Millennium.”

- Wall, Revelation, 173; Aune, Revelation 6–16, 768; Gorman, Reading Revelation Responsibly, 132–33, 179.

- Beale, Revelation, 716; Smalley, Revelation to John, 349.

- John D. Barry, “Mark of the Beast,” Lexham Bible Dictionary (Bellingham, WA), 2016.

- Mounce, Revelation, 259; Smalley, Revelation to John, 349; Ford, Revelation, 215.

- Beale, Revelation, 715; Smalley, Revelation of John, 349; Morris, Revelation, 168.

- Aune, Revelation 6–16, 767; Mounce, Revelation, 259.

- Mounce, Revelation, 259.

- Aune, Revelation, 6–16, 767–68.

- Mounce, Revelation, 259.

- Beale, Revelation, 715; Judge, “Mark of the Beast,” 160.

- Smalley, Revelation, 349.

- Aune, Revelation, 6–16, 767.

- Smalley, Revelation to John, 349.

- Smalley, Revelation to John, 359.

- Bauckham, Climax of Prophecy, 447–48.

- Mounce, Revelation, 311.

- Irenaeus, Adversus Haereses, 5.29–30.

- Wright, Revelation, 116–18.

- MSS that add καί before συναγαγεῖν (א 051 MajTA sy) understand a parallel syntax.

- Meshech and Tubal are not the original forms of Moscow and Tobolsk! (They are the Hebrew names of the East Anatolian groups known to classical historians as the Moschi and the Tibareni.)

- “By John’s time, Jewish tradition had long since transformed ‘Gog of Magog’ into ‘Gog and Magog’ and made them into the ultimate enemies of God’s people to be destroyed in the eschatological battle” (Boring, 209).

- See Beale, Revelation, 722–28; Smalley, The Revelation, 352–53; Hendriksen, More than Conquerors, 150–51; Hughes, Revelation, 154–55)

- Smalley, Revelation to John, 353.

- Milton S. Terry, Sibylline Oracles (Hunt & Easton, Cranston & Stowe, 1890), 1.325.

- Francis X. Gumerlock, “Nero Antichrist: Patristic Evidence for the Use of Nero’s Naming in Calculating the Number of the Beast” (Rev 13:18), Westminster Theological Journal 68, no. 2 (September 1, 2006), 347–60; Ethelbert Stauffer, Christ and the Caesars: Historical Sketches. (Eugene, Oreg.: Wipf & Stock, 2008), 179.

- Outline excerpted from: Barry, “Book of Revelation,” Lexham Bible Dictionary, 2016.

- Craig Keener, Book Study: Revelation, “An Overview of Commentaries” (Lexham Press, Bellingham, WA), 2016.

- David deSilva, Unholy Allegiances: Heeding Revelation’s Warning (Hendrickson), 2013.

- deSilva, Unholy, 2013.

- deSilva, Unholy, 2013.

- deSilva, Unholy, 2013.

- Revelation, I, pp. lxviii–lxxxi. Ozanne adds 3:4, 7, 29; 7:2, 20; 8:2; 9:21 (Influence, pp. 66–81).