The Dead Sea Scrolls don’t interest only academics and scholars. Many average Christians have questions, too. Read on for the answers to the most common questions!

- What are the Dead Sea Scrolls?

- How were the Dead Sea Scrolls discovered?

- How old are the Dead Sea Scrolls?

- How can scholars tell how old a manuscript is?

- Who wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls?

- What do the Dead Sea Scrolls tell us about the history of the Bible?

- Do the Dead Sea Scrolls help us understand the New Testament?

- Did the Dead Sea Scrolls reveal other texts outside the Bible?

- How can we read the Dead Sea Scrolls?

What are the Dead Sea Scrolls?

The Dead Sea Scrolls are fragments of about a thousand ancient manuscripts written mostly in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek.

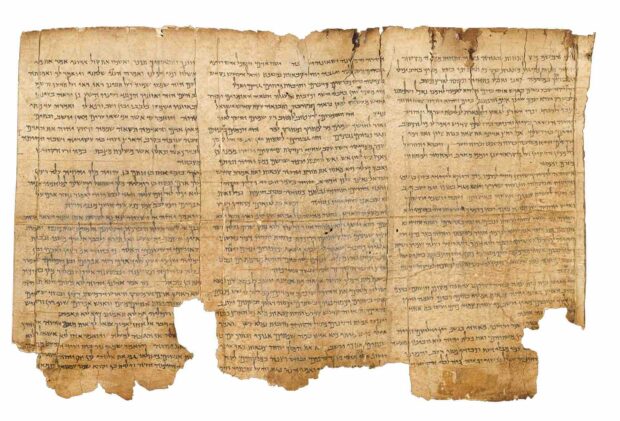

They were discovered in 1946–47 in caves in the Judean Desert near the Dead Sea. The fragments were written on parchment (animal skins prepared for writing) or papyrus, and what is left of them had to be painstakingly pieced back together by scholars based on the material, the handwriting, and of course the texts. About 25 percent of these scrolls are copies of texts that would eventually be included in the canon of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. The rest of the manuscripts contain mainly other Jewish literature from the period, letters, and contracts.

The Dead Sea Scrolls are identified by a standard reference system that includes:

- The number of the cave where the manuscript was discovered (if multiple caves at a site yielded manuscripts)

- The name of the site where it was discovered (e.g., Q = Qumran, Masada, Wadi Murabba‘at, Naḥal Ḥever)

- The identification number of the scroll for that particular site OR the name of the manuscript that describes its contents.

So, for instance, 4Q52 (aka 4QSamuelb) was found in Qumran cave 4, and it is number 52 in the publication list of scrolls from this cave. The title with superscripted “b” indicates that this is the second listed copy of the books of Samuel from this cave.

How were the Dead Sea Scrolls discovered?

The seven most famous and well-preserved Dead Sea Scrolls were found in the winter of 1946–47 by a Bedouin herdsman named Mohammed ed-Dib (lit., “the wolf”), who purportedly threw a rock into a cave after a stray animal and heard a loud crash. Upon further investigation he found several scrolls inside clay jars, which he subsequently sold. When these scrolls came to the attention of scholars, they were quickly recognized as being among the most important archeological discoveries of the twentieth century. The cave in which these scrolls were found eventually came to be called Qumran cave 1, named after the nearby ruins of Qumran.

After this, illegal Bedouin excavations and professional archeologists raced to find new scrolls in nearby caves. The Bedouin first found the largest group of fragments in what would be numbered cave 4, right next to the site of Qumran. They sold fragments to the archaeologists, who caught wind of the discovery and started excavating the cave officially. In all, cave 4 yielded thousands of fragments that were pieced back together by scholars into over 500 different manuscripts.

Over the next decade or so, Bedouin and scholars discovered and excavated a total of eleven caves with scrolls around the site of Qumran, as well as additional caves at other sites in the Judean Desert like the fortress Masada, Wadi Murabba‘at, and Naḥal Ḥever. Just recently in 2019–2020, the Israel Antiquities Authority discovered additional Dead Sea Scroll fragments of a Greek copy of the Minor Prophets in a cave in Naḥal Ḥever called the “Cave of Horror”—because of the forty skeletons found there of people who died fleeing the Romans.

Most of the Dead Sea Scrolls are now kept by the Israel Antiquities Authority in Jerusalem, but a few manuscripts are in other locations like Amman (Jordan), Paris, and Rome. Since 2000, a number of fragments claimed to be authentic Dead Sea Scrolls have been sold to private dealers, but most or all of these are now generally believed to be modern fakes.

How old are the Dead Sea Scrolls?

The Dead Sea Scrolls from the Qumran caves were written between about 300 B.C. and A.D. 68, the date when the site of Qumran was destroyed by the Roman army. Some caves from other sites yielded a few earlier contracts from 350 to 300 B.C., and a list of names on papyrus from before the destruction of Jerusalem in 587/586 B.C., but no literary texts from before the first century B.C. were discovered.

Most of the manuscripts from sites other than Qumran are from the first and second centuries A.D.—up until the time of the Second Jewish Revolt that was put down by the Romans by A.D. 135/136—and these are a mixture of literature (including copies of the Hebrew Scriptures and Greek translations), contracts, and letters.

The just over two hundred biblical Dead Sea Scrolls are the oldest copies of the books of the Bible in existence. Some of the earliest biblical scrolls were probably written in the third century B.C. (e.g., 4QSamb, 4QExo–Levf, 4QJera, 4QpaleoDeuts), which allows scholars unique insight into the ancient copying of these books. The majority of biblical scrolls seem to come from the first centuries B.C. and A.D.

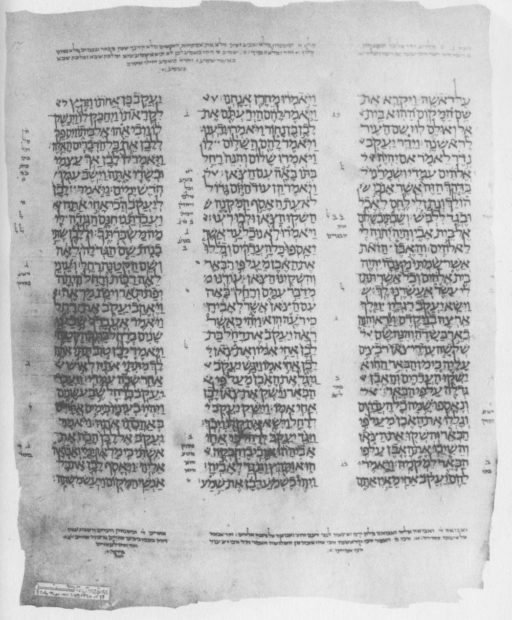

Before the discovery of the scrolls, the earliest copies of most of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament came from the tenth and eleventh centuries A.D., with only a handful of fragments from a few centuries earlier. The oldest complete copy of the entire Hebrew Bible/Old Testament is the famous Leningrad Codex (written in A.D. 1008/09), on which the standard modern critical edition is based. Thus, the Dead Sea Scrolls are about one thousand or more years older than the copies that had previously been known.

How can scholars tell how old manuscript is?

Sometimes writers of ancient letters and contracts wrote the dates explicitly on their manuscripts, but Hebrew scribes copying literature did not include dates. Sometimes the contents of the texts or the archeological context in which they were discovered also give important information for dating manuscripts. And in recent decades, around sixty Dead Sea Scrolls have been radiocarbon-dated to give a range of possible dates. But in most cases, specialists in ancient Hebrew handwriting called paleographers have to assign approximate dates to the manuscripts based on where their scripts fit in the history of the development of Hebrew handwriting.

Who wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls?

The Dead Sea Scrolls were written by many different people in many different times and places in the Judean Desert. The largest and most famous collection of scrolls came from Qumran, a simple site that was inhabited in the first centuries B.C. and A.D. by an ascetic religious group focused on ritual purity and centered around the study of the Scriptures and other texts. A large portion of the non-biblical scrolls from Qumran reflect the distinctive ideology of this group, which seems to have been at odds with the leadership in the Jerusalem temple. Given the striking similarities between the Qumran community and a Jewish sect known as the “Essenes” (described by the historian Josephus and other classical sources), most scholars think that the two were related.

There is evidence that some of the Qumran scrolls were likely produced on site, since archeological excavations at Qumran discovered an unusually large amount of writing and bookmaking materials such as inkwells and straps for tying scrolls. Scholars have also noted that a few scribes each copied multiple manuscripts that were discovered in the Qumran caves, which could suggest that they were working at Qumran. And many of the manuscripts appear to be informal scraps that would have been unlikely to be imported to the site and thus were likely written at Qumran. On the other hand, many of the manuscripts were written before Qumran was even inhabited by the group, and these must have been produced elsewhere. Furthermore, there appear to be hundreds of different writers with distinctive handwriting represented in the Qumran corpus, which can only be explained if many of them were written elsewhere. The Qumran site is simply too small to have accommodated that many scribes in such a short period of time.

The Dead Sea Scrolls also tell us important information about the training, skills, and work of their writers. Many of the legal contracts were likely written by professional scribes trained to produce them. On the other hand, letters and copies for personal use in informal handwriting must have been written by literate individuals, who may or may not have been scribes by trade. And many beautiful copies of Scripture and other esteemed literature from the end of the first century B.C. and later show that by at least this time there was a highly skilled class of professional book scribes who produced copies to exacting standards for a book market of some sort.

What do the Dead Sea Scrolls tell us about the history of the Bible?

Do the Dead Sea Scrolls contradict or prove the Bible? This is a fundamental question for Jewish and Christian believers who accept the Bible as sacred Scripture, as well as for many others interested in the Bible for a variety of reasons. But it is also a difficult question to answer in a straightforward way, since the Dead Sea Scrolls reveal a very long and complex history of the Bible.

First, it is important to discuss which books of the Bible were included among the Dead Sea Scrolls. Almost all of the books of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament were discovered at Qumran, with the largest numbers of copies (or excerpts) coming from the Pentateuch (aka the Torah, or the five books of Moses), Isaiah, and the Psalms. Only three books are not attested in fragments from Qumran: 1 Chronicles, Nehemiah, and Esther. First Chronicles goes together with Second Chronicles, of which one fragment has survived. Nehemiah in some traditions is connected with Ezra, of which fragments have been preserved. But no copies of Esther were found at Qumran, though some scholars have argued that there are references to the story in other literature from Qumran. Of the books of the Apocrypha, only Tobit, Ecclesiasticus/Ben Sira/Sirach, and the Epistle of Jeremiah were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls. In other words, most (if not all) of the books of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament were kept at Qumran, whereas most of the Apocrypha appear not to have been.

It is important to remember, however, that there were no complete Bibles in the times of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Instead, individual books and collections were written on separate scrolls. Neither do we have any lists of which books the Qumran community considered sacred Scripture and/or canonical. Scholars try to determine this by considering the number of copies of each book, as well as how often they were cited and in which ways. Based on these criteria, some books outside the Bible like 1 Enoch and Jubilees seem to have been highly esteemed, and some have argued that they were received as Scripture in the same way as the traditional biblical books. But there is, as yet, no consensus on which books the community accepted or whether they even distinguished books in this way.

In addition to which books were included, the Dead Sea Scrolls provide crucial information about the composition and copying of the biblical books. Some scrolls are called proto-Masoretic by scholars because they are the predecessors of the medieval Hebrew manuscript tradition that was preserved by Jewish scholars called the Masoretes. These often match medieval and modern Hebrew Bibles essentially word for word and even letter for letter, which demonstrates the incredible accuracy and precision of copying over more than two thousand years of transmission. Other Dead Sea Scrolls have more significant differences, which show that sometimes texts were changed due to scribal errors in copying or else intentionally, usually in order to make the text clearer or more consistent. In cases where the manuscripts differ, scholars study and debate which variants were the earliest and which were later changes.

In a few cases, the Dead Sea Scrolls reflect different versions of entire biblical books from the final stages of their compilation and editing. The most famous example is from Jeremiah, where 4QJera has a text very similar to the later Jewish manuscripts, but 4QJerb and 4QJerd are very close to the ancient Greek translation of the book, which is significantly shorter and places the oracles against the nations (chs. 46–51) after 25:13 and in a different order. Many (though not all) scholars think the shorter version was earlier and that the version preserved in the medieval Hebrew manuscripts and modern English Bibles is a revised and expanded version of the book. In cases like these, the Dead Sea Scrolls may provide a unique window into the earliest history of the Bible when it was still being written and edited.

Do the Dead Sea Scrolls help us understand the New Testament?

A few scholars early in the study of the Dead Sea Scrolls suggested that some very small Greek fragments from Qumran were copies of New Testament books, but this idea was quickly debunked as the full contents of the collection became known and the manuscripts were more closely studied. There were no Christian texts discovered at Qumran or elsewhere among the Dead Sea Scrolls, nor is there any direct evidence of contact between the Qumran community and the early Jesus movement. Nevertheless, the Dead Sea Scrolls provide important background information and textual parallels that have helped scholars understand the New Testament better in light of its first century A.D. Judean context.

For example, the Dead Sea Scrolls illustrate the complex multilingual context in which the New Testament was written. They also demonstrate the diverse types of texts that were available to the New Testament authors, including versions of the Greek Old Testament and other Jewish literature that were widely known in those times, but were largely lost to later Jewish and Christian communities. Texts about Enoch seem to have been especially popular, which helps explain the quotation from Enoch in Jude 14–15.

The interpretive practices seen among the Dead Sea Scrolls also shine much light on the use of the Old Testament by New Testament authors. Much like the New Testament authors, the authors of commentaries and other interpretive texts from Qumran show an interesting tendency to interpret the Old Testament texts in light of their own situations, expanding the meaning of the texts beyond their original intention so as to relate the earlier texts to the later authors’ own concerns. From this perspective, the Psalms and Prophets were speaking not just about past times, but also about the contemporary experiences of the nascent church or the community associated with Qumran. Thus, the voice crying in the wilderness and preparing the way of the Lord in Isaiah 40:3 is related to either John the Baptist or the community in the Judean Desert, respectively. Old Testament texts were not just about the historical past, but also about eschatological realities. The Dead Sea Scrolls demonstrate that this manner of interpretation was not strange or particular to the New Testament authors, but was a widely accepted interpretive practice at the time.

The Dead Sea Scrolls also give firsthand insight into some of the ideas and practices that were current around the time of Jesus. Earlier generations of scholars had been largely reliant on recollections of uncertain historical accuracy culled from later rabbinic literature for information on this important period. Many ideas evident in the DSS have parallels in the New Testament, such as strict deterministic dualism between the righteous and the unrighteous, identification of the community as the righteous remnant within Israel, messianism, apocalypticism, eschatological expectation, and an emphasis on baptism and repentance. Several texts from Qumran show a lively interest in exalted messianic figures, and the community may even have been looking forward to multiple Messiahs to fulfill both priestly and royal roles. Sometimes there are even specific verbal parallels between the Qumran scrolls and the New Testament, such as the references to the “works of the law” in the halakhic (applicational) letter 4QMMT and Paul’s letters.

This is not to say that the authors of the DSS always—or perhaps even often—agreed with the early Christians. For one, they were very much concerned with strict legal interpretations. In a commentary on the book of Nahum (4Q169), the author calls his opponents “the seekers of the smooth things (ḥalaqot),” which may be a pun on the more lenient legal rulings (halakhot) of the Pharisees. The movement associated with Qumran was also largely priestly both in origin and leadership, strongly hierarchical, and strictly regulated, in sharp contrast with the early Jesus movement. Furthermore, the spread of early Christianity with the incorporation of believing Gentiles differs greatly from the perspectives of the authors of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Did the Dead Sea Scrolls reveal other texts outside the Bible?

In addition to biblical texts, legal contracts, and letters, the Dead Sea Scrolls revealed an extensive library of other Jewish literature. Some of these texts share the distinctive terminology, beliefs, and practices of the Qumran community and its predecessors. One of the most famous of these is the Community Rule (1QS), which lays out the beliefs, practices, and rules of the community. The Qumran caves also yielded biblical commentaries, prayers, liturgical works, calendar texts, wisdom literature, legal texts, apocalyptic works, creative retellings of stories, and other types of compositions.

One of the most famous and important examples of such literature is the book of 1 Enoch, which has survived fully only in translation in late Ethiopian manuscripts. Portions of the book are known in other languages and were found in several Aramaic (and possibly Greek) copies from Qumran (every part except the Similitudes). The book of 1 Enoch—named after the biblical figure who features throughout the book—is composed of five main sections, which in early times appear to have been separate books that were later compiled together:

- The Book of the Watchers (chs. 1–36) about the story of the fallen angels in Genesis 6

- The Similitudes/Parables (chs. 37–71) with references to an exalted Son of Man

- Astronomical Enoch (chs. 72–82) about the solar calendar

- The Dream Visions (chs. 83–90) recounting Enoch’s apocalyptic dreams

- The Epistle of Enoch (chs. 91–108) about final judgment with an epilogue about Noah

The book of Enoch was apparently very popular in some early Jewish and Christian circles, but it lost favor in the first centuries A.D. and was not admitted into the canon except in the Ethiopian church.

Another significant book attested in many copies from Qumran is the book of Jubilees, a retelling of Genesis and parts of Exodus influenced by the beliefs and practices evident in the Enochic literature. And one final fascinating example is the Copper Scroll, the only metal scroll found in the Judean Desert. The Copper Scroll purports to be an inventory of the hidden temple treasures, though no such treasures have been discovered (at least in modern times).

How can we read the Dead Sea Scrolls?

High-resolution photographs of most of the Dead Sea Scrolls are available online at the Israel Antiquities Authority’s Leon Levy Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library. English translations of the biblical Dead Sea Scrolls are available in the Dead Sea Scrolls Bible. There have also been several English translations of the non-biblical scrolls, e.g., The Dead Sea Scrolls in English by Geza Vermes [gay-za ver-MESH], The Dead Sea Scrolls Study Edition by García Martínez and Tigchelaar, and The Dead Sea Scrolls: A New Translation by Wise, Abegg, and Cook.

Interested readers may also benefit from reading further introductory material about the scrolls. The classic work The Meaning of the Dead Sea Scrolls by VanderKam and Flint provides a more detailed introduction to help readers understand the contents of this collection in their ancient context. And Logos also offers a full 12-unit video course introducing the scrolls by Dead Sea Scrolls scholar Andrew Perrin.

***

Related resources

Take a look at how you can study the Dead Sea Scrolls with the Logos Bible study app (starting at free), then explore books and courses below.