by Vinh T. Nguyen

In his recent post Four Reasons to Master Koine (and to Leave Attic Alone), Tavis Bohlinger made a plea to specifically focus on Koine in order to master “this particular type of Greek as thoroughly as possible.” This post continues a collegial dialogue about studying Greek which includes an article from Shawn Wilhite on the importance of reading background texts of the New Testament.

Since Koine Greek did not happen in a vacuum, how can one master the language (let alone do it as thoroughly as possible) by neglecting the period from which it developed—a period classified as the highest point of the Greek language? During the Hellenistic period (332–63BC), Attic Greek became Koine Greek so that all people could communicate. This is the period from which the Greek of the New Testament was written—a period where the language would undergo many changes1—and would greatly affect how Greek would come to be studied and taught.

As I write this post, I find myself transported back in time to my first ever Greek course during my undergraduate studies. The professor, full of energy and enthusiasm, entered class and proceeded to scribble on the dry erase board (though forever etching into my mind) the following formula: Knowledge + Practice = Skill. He then said something to the effect of, “we all have knowledge, some more than others and will require less practice while others require more practice, to develop this skill. The lightbulb comes on at different times for different folks.”

I wanted to believe that I had a place amongst the former group who required “less practice,” and whose filament in this professor’s metaphorical lightbulb would quickly shine brightly for all to see. After receiving the marks from my first Greek exam, the harsh reality set in that I might be in the latter group. Admittedly, I still feel the sting of that day, but I am grateful for it because my academic career, even up until the present, is spent living amongst the group that realizes the importance of “practice, practice, practice.”

While this post is primarily focused on mastering Greek in relation to Greek grammars, let me first say that I have yet to meet a Greek professor who claims to have mastered Greek in such a definitive way that they have no further questions about the language. There is a distinct difference between knowing Greek grammar and syntax and understanding Greek as a language which I hope to demonstrate further below. Mastering Greek takes a lifetime of devoted study and practice and even then, you will still sense that you need more time. Frederick Danker is said to have worked 12 hours a day, six days a week, for ten years on just revising the BDAG lexicon. When asked in an interview about whether this was true, he simply replied “Well, we did take vacations.”

We can’t all be Danker, nor should we try to be (such commitment is unrealistic for most); however, this serves to demonstrate the hard work that is necessary for understanding or “mastering” Greek.

Dethroning grammar as king

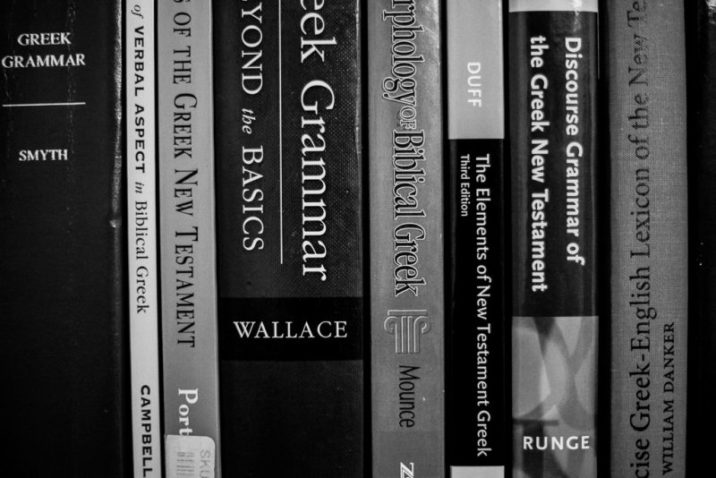

Any student who has studied Greek beyond undergrad is likely to have encountered several different Greek grammars. Does the Greek grammar you study from really matter? Will it have an impact on the quality of your exegesis, research, or your preaching? I would suggest that these are very important but often neglected questions. One needs to do little more than pick up a modern commentary that comments on the Greek text to realize that not many (including seasoned scholars) have given much consideration to this question. The short answer is, yes. The resources you avail yourself to will impact your research, your exegesis, and your preaching.

The reality is that every Greek student has to start somewhere and, for most of us, that starting place is up to the discretion of our undergraduate or seminary professors and the textbooks they select.

While there are many grammars available on the market today, not all of them approach the language the same way nor are they equal in quality. Every Greek grammar has a time and a place in history. Understanding the time and place of the grammar you choose to use is just as significant for learning the language as what is contained inside.

I am well aware that learning Greek early on is, in many ways, a mechanical act (i.e., memorizing charts, paradigms, principal parts, etc.). You are overwhelmed with the amount of information you have to memorize for your next quiz or exam. All you’re trying to do is establish some kind of foundation to get you by, so you can build on it at a later time. I empathize with you because I have been there myself. Let me explain why I think understanding the time and place of the grammar you use is critical to both the foundation you establish for learning Greek and your subsequent understanding of the language.

In seminary, I had the privilege to serve as a teaching assistant to one of the Greek professor on campus. In our last year together, the two of us spent countless hours on our own and together in the office reading, researching, and picking each other’s brains about the Greek language (checking out every book available in the library on the topic and even requesting them to order more!). There were times where we literally went back to the drawing board (dry erase board) to challenge our understanding of Greek, so in many ways it felt more like starting over (I hope this encourages some readers to not be afraid to have meaningful conversations with your professors and mentors and to ask the hard questions). This wasn’t a matter of building on a previous foundation more than it was pouring a new one. This goes back to my earlier distinction about knowing grammar and syntax and understanding the Greek language which takes us back to the question concerning what grammar to use or learn from—a question often asked by many students who want to go deeper in their Greek studies.

Greek grammar for the most part can be divided into three major periods. Much more can be said about each period, but I’ll just mention a few salient points that impacted Greek grammars.

The Rationalist Period (18th–19th century)

In many ways, this period was concerned with making logical and rational sense of the Greek language. This is the period where the ideas of “traditionalist grammar” first appeared. Some of these ideas include relying on Latin rules which were very important and heavily used; viewing written language as more important than spoken language; and the desire to study some regularized form of the language (Attic Greek was seen as the standard). Georg Winer was the first to write a major NT grammar during this time which followed the rationalist principles of his day. Another major grammar that appeared was Blass and Debrunner’s translated by Funk (BDF) which functioned to note the places where the Greek of the NT departed from Classical Greek. Thus, Hellenistic Greek was viewed as some deficient form of Classical Greek.

One other major movement during this period was the rendering of an aspectual language into a tensed language. This is significant because something is always sacrificed in such an exchange. Either you sacrifice the aspect of the original language or you sacrifice the tense of the receptor language (it’s the main issue of rendering a non-configurational language into a configurational language). You can begin to see how some of the concerns of this period impacted the grammars that were developed.

The Comparative-Philology Period (1860–1916)

One of the major goals of the comparative-philology period was discovering how particular languages were connected to each other. This period was highly concerned with diachronic study (studying how languages were connected to each other and changed throughout time). If certain languages had so many similarities, what happened that caused all the major changes or deviations? Thus, major language families were developed during this time (e.g., Indo-European or Proto-Indo-European Languages: Celtic languages, Italic languages, Greek languages, Germanic languages, Balto-Slavic languages, Armenian language, Indo-Iranian languages to name a few). The massive grammar from A.T. Roberson is indicative of this time period. Regarding the accusative case, for example, you will notice Robertson talking about how the accusative case is compared with Latin’s accusative case or Sanskrit’s accusative case rather than seeing how each case was related to other cases within its own system synchronically.

The Modern-Linguistic Period (1916–present)

The modern linguistic period is typically identified with synchronic study (how a language is studied at a particular point in time) and is perhaps of greatest interest to you as a reader since the grammar you are working with is likely from this period. This period, for better or worse, has seen the largest production of Greek grammars and not all are of equal quality. There are probably several different factors for the myriad of grammars being produced, but one prevailing factor is the inclusion of modern research and linguistic insights not available in previous grammars. If you do a comparative study of grammars that have been produced within the last decade, you will notice some major changes in how the Greek verb is understood—several which are reflective of different time periods.

I have selected three grammars to demonstrate my point (specifically these three because they were the requirement at the institutions where I’ve studied): 1) Bill Mounce’s Basics of Biblical Greek; 2) Gerald Steven’s New Testament Greek Primer; and 3) Stanley Porter, Jeffrey Reed, and Matthew O’Donnell’s Fundamentals of New Testament Greek.

The first two grammars view the Greek verb temporally (often referring to tense as it relates to time), albeit in different ways, while the third grammar views the verb aspectually. Mounce’s grammar is more reflective of the modern-philological period where Aktionsart categories were developed and prevalent. The aorist is not a once-for-all type of action (punctiliar or historical tense). Steven’s grammar, on the other hand, is more reflective of the rational period and views the aorist an undefined action that is past time in the indicative (historical tense). Porter/Reed/O’Donnell’s grammar is reflective of the modern-linguistic period and views the Greek verb to be atemporal, encoding aspect only (Rodney Decker’s Reading Koine Greek is similar in this regard).

In Tavis Bohlinger’s original post, he posited that “Grammar is King.” He recommended choosing a book of the New Testament, then starting with Wallace or Siebenthal’s grammar, and taking advantage of other available tools to work through the text. Then repeat the process with a different grammar and you’ll be mastering Greek.

I have attempted to demonstrate above a few reasons why such an approach is not conducive for mastering the language and why grammar ought to be “dethroned as King.” Each grammar has a time and a place from which it came or reflects. Different times and places held different understandings for the Greek language (verbs just being one example). The same thing can be said for syntax grammars and lexicons.

Impact on exegesis

If solid exegesis is one of your goals for learning and mastering Greek, then understanding the language and not just the grammar should be of utmost importance. Just selecting a few works in Koine (grammars, lexicons, syntax books, etc.) without knowing their approach to Greek is certainly not going to render the best exegesis. If your starting point isn’t grounded, can you expect your conclusions to be? By repeating the process with a different grammar each time, you will inevitably end up with different exegetical results because each Greek grammar is not doing the same thing.

In fact, they are often conflicting in the information they convey so you can expect conflicting results. You might have sensed an internal conflict or even some confusion during your own studies if you’ve ever taken classes where you were introduced to a new grammar (the shift from the rationalist period’s temporal view of the verb to the historical-philological Aktionsart view is challenging enough, let alone shifting to an atemporal aspect view). The problem concerning exegesis can be seen in many modern commentaries where the primary grammars used are often conflicting grammars which leads to confused exegesis (but that’s a topic for another day).

Four insights for selecting the right grammar:

- Be aware of the time and place of the grammar. While there currently isn’t any simple guide that places each grammar within its proper period, paying attention to how verbs are treated is a good starting point. Does the grammar use temporal language (if so, does it use Aktionsart categories or not) or does it use aspectual language? Hopefully my brief explanations above offer a little help as well.

- Be aware of the latest insights and research in Greek studies. While there are better ways to spend your time than entering into endless debates about Greek on social media, use resources such as Nerdy Language Majors, New Testament Greek Study, The Logos Academic Blog, etc. as an avenue to see what is currently being discussed. This will help you select grammars that include the latest insights and research.

- Start working through important monographs on Greek. There is no shortage of important monographs that you can begin working through to gain a better grasp of the Greek language. Yes, this will take a little bit more time, but it is more than doable if you manage your time wisely. The effort will be worth it. See Wilhite’s post for some starting points on how to structure your study time. The insights you gain from the focused work of monographs will help you tremendously in determining the value of the Greek grammars you encounter.

- Don’t be afraid to challenge yourself and your previous understandings. I’ve always thought that learning Greek grammar from a variety of grammars, coupled with a few syntax books from Greek exegesis courses, and a couple helpful lexicons would make me a decent Greek scholar and exegete. After all, isn’t this how many of us are taught to do exegesis (gather all of your sources and see what they have to say)? Changing your position in the learning process takes a lot of humility. Don’t be afraid to challenge the grammars you’ve learned from and to select better grammars as your knowledge grows from studying Greek as a language and not as a grammar.

So, do you wish to be a dilettante, or an expert? The true expert will not just read through Greek grammars without discretion. Choose wisely, know the background and history of Greek language study, and pursue informed expertise in your journey to mastery of Koine.

Learning Greek isn’t a burden, it is a privilege. One that many around the world wish they had the opportunity to do. May we continue to be faith exegetes, researchers, and preachers in devoting our efforts to understanding the language of the New Testament.

Vinh Nguyen is a New Testament PhD student at McMaster Divinity College in Hamilton, Ontario Canada. He also holds an M.A. in Biblical Languages from New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary and a B.A. in Biblical Studies and Christian Ministry from Ouachita Baptist University.

Find more on Greek grammars on logos.com and study the language in greater depth with the Logos platform.