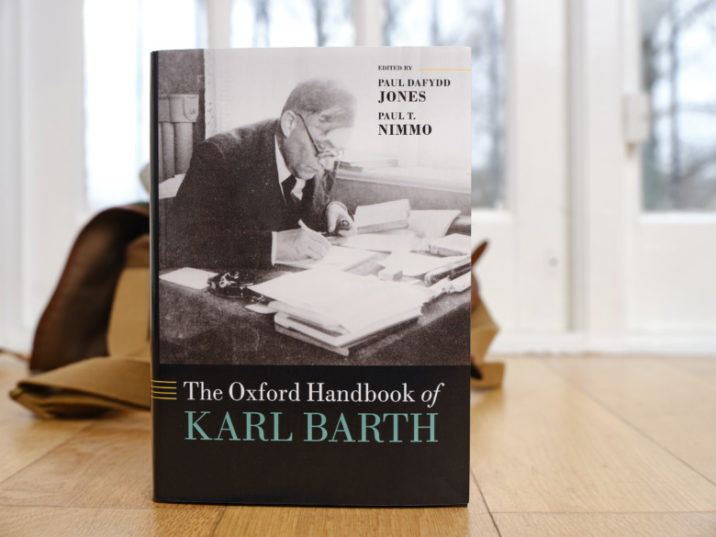

The fifth interview in our series on the OUP Handbooks is with Paul Dafydd Jones and Paul T. Nimmo, co-editors of The Oxford Handbook of Karl Barth. In what follows, we discuss various aspects of the work including the depth of the essays and what makes this resource distinct amongst other works on Karl Barth.

What is special about the OUP Handbooks, and why should students and scholars use them in their research?

PDJ: One of the distinctions of the OUP Handbooks, as I see it, is that they manage to hit an elusive sweet spot: they provide crisp accounts of some thinker, issue, problem, or concern within a particular field of study, while also showcasing new trajectories of reflection. So if someone wants to find out, say, about Ancient Nubia, Indian Foreign Policy, Neurolinguistics, or – to move closer to home – Feminist Theology, Martin Luther, and the Prophets, and realizes that life is too short to spend time with mere summaries … then OUP Handbooks are a great place to start.

I also think it noteworthy that the Handbooks tend to be long, multi-chaptered volumes, filled with pieces by scholars who write from a variety of perspectives. That helps readers to understand that fields of study are rarely marked by easy consensus, but are instead sites of ongoing arguments, debates, and confusions.

PTN: I would agree with that, and I have a run of Oxford Handbooks on my bookshelves. The appeal is about the balance they achieve between reliable exposition and insightful engagement, and the breadth they offer in terms of distinct voices of reception and critique. As a result, they manage to serve both as accessible resources to students and as critical resources for researchers.

It is the service of the OUP editors – in our field, the fantastic Tom Perridge, Senior Commissioning Editor in Religion – to take great care to curate the series of Oxford Handbooks along these lines in order to maintain their excellent reputation. In our case, Tom provided both advice and encouragement along the way, and was particularly helpful early on in conceiving the volume.

Tell us a bit about what you wished to accomplish as editors of The Oxford Handbook of Karl Barth and how you think that goal was achieved.

PTN: I think that our primary goal as Editors was to offer to readers a really good handbook to Barth’s work – the kind of volume that you could just reach down from the shelf or open up online to gain a clear and concise account of what he thought about a particular tradition or a given theme or how he might respond to some current issue. Barth is one of those fascinating figures in the tradition of theology whose voice is always worth hearing, regardless of whether you agree with him or not. He thought about the major theological issues against the backdrop of really significant events, and for all that he was deeply embedded in the church and its tradition, he came up at points with some fairly radical answers. We wanted to communicate in our volume something of this multi-faceted richness of Barth, his life and his work.

I would like to think that this volume achieves our goals both by virtue of the very fine list of scholars whom it invited to contribute – a veritable who’s who of Barth studies – and by virtue of the way in which it is structured to display something of the breadth of Barth’s life and work and of its potential in the present. As in any project, of course, there are points at which we would have liked to have done more; but on the whole we hope to have covered our aims as well as we could.

PDJ: I agree with all the above (thankfully: it would be an unwelcome shock, were I to discover that we had different goals for the volume!). We certainly wanted to provide something like a dogmatic conspectus, focused mainly on the Church Dogmatics. While the Handbook is hardly a substitute for the real thing, Barth is a fairly intimidating author. His prose can come across as brash, brilliant, subtle, and cryptic, all at the same time; and, as Paul Nimmo says, his work is both deeply indebted to the traditions of the past and willing to strike out on its own terms. Trying to come to terms with all that is quite a challenge, and one of the goals of the Handbook is to help readers meet that challenge.

Looking back in the direction of the first question, I also think that one of our goals was to avoid any homogenization of Barth studies – or, to put it more positively, to demonstrate that scholarly fascination with his work has branched out in many directions. It’s a good thing that Barth is no longer viewed as a representative of “neo-orthodoxy,” and that the Dogmatics isn’t read as a restatement of claims voiced by the magisterial Reformers. That way of thinking, thankfully, is passé. What is perhaps less obvious, at least to those who come at Barth from a bit of distance, is that Barth studies is diversifying in salutary ways. Not just in terms of the scholars involved – it’s better than it was, but there is still a long, long way to go, as with most other fields focused on the academic study of Christian thought – but in terms of Barth being read from a wide range of standpoints. This is the reason that, in addition to sections that consider Barth’s intellectual biography and particular dogmatic loci, we have a section entitled “Thinking After Barth.” That section includes, among other things, treatments of Barth and race, Barth and gender, Barth and environmental theology, and Barth and religious pluralism.

For readers unfamiliar with your work, can you tell us about your respective backgrounds and how that prepared you both as editors of the Handbook?

PDJ: The deep background, of course, is reading a ridiculous amount of Barth, writing a dissertation on Barth, publishing a book about Barth, and writing many shorter articles and chapters about Barth, lecturing and teaching Barth… and continuing to read Barth. But I figure this question asks for a bit more disclosure, so I’ll say this. I first read Barth when I was an undergraduate, in a seminar led by Paul Fiddes. We did not get along (me and Barth, that is; Fiddes was great). I definitely felt compelled by the text – we focused on Church Dogmatics I/1 – but I also found it utterly exasperating. High-handed, restrictive, and austere; lacking much in the way of explicit political “bite.” However, when I read Barth seriously again, during PhD studies, the experience was quite different. I realized that my initial impressions were off target. The dialectical energy of the text, the emphasis on God’s love, the vision of God’s empowerment of creaturely agency, and an abiding concern to connect Christian theology and Christian faith with the ongoing reformation of the church and society – that all came to the fore, as did an awareness that Barth didn’t expect me to agree with everything he was saying, so long as I listened to what he was saying. I certainly didn’t become a “Barthian” at that point (I don’t think I’m one now, either), but it was the beginning of a fascination with his work and ideas that, in a complicated way, made editing the Handbook a real privilege.

PTN: I confess that I share the same “deep background” as my esteemed co-Editor … My own dissertation was on Barth, and since its publication I have continued to be engaged with his thought by way of articles, chapters, essays, and teaching. I published a textbook on Barth for the perplexed, and am currently finishing a monograph on his doctrine of the Lord’s Supper. But to follow Paul’s autobiographical turn for a moment, my first serious exposure to Barth’s work was as an Honours student in a seminar at Edinburgh, set the task of reading excerpts from Church Dogmatics IV/1. The text was hugely intimidating, of course – not least in terms of its length! – and I cannot pretend to have fully grasped its substance at that time. But I remember being affected profoundly by the text in two ways. First, it seemed to me that in reading Barth, I was reading work of real substance: rooted in Scripture, engaged with tradition, creative in thinking. And second, it seemed to me that thinking with Barth, as a nascent Reformed theologian rather hesitant about the legacy of Calvin, I discerned a theology that I found habitable for today. And that led me to further work on Barth at Masters and at doctoral level. I confess that I am still affected by Barth, and profoundly so, in both these ways. I suspect, correspondingly, that I am more closely thirled to his work than Paul Jones is, but I also retain with Paul the desire to interrogate Barth critically, and have departed from Barth’s position at quite a few points down the line.

What distinguishes the collection of essays in the Handbook from other collections of essays on Karl Barth?

PTN: Certainly, there are some excellent resources on the work of Karl Barth available, and this volume shares in some of the features of those: it has a terrific list of both established and upcoming scholars, it features voices from diverse countries and contexts, and it offers a wide-ranging array of substantive material. In terms of what is distinctive about our handbook, I would highlight perhaps two different aspects.

First, it seeks to hold in tension two rather different – though not competing – legacies of Barth. The first legacy is that of a traditional systematic theologian of the highest calibre, one who authored a series of works of historical and dogmatic theology – as well as of historical theology and biblical exegesis. These works not only engage the tradition at great length (!) – they also do so with great insight and knowledge. The second legacy is that of an extravagantly dialogical thinker, one constantly and relentlessly engaged both with other church traditions and theological positions and with political matters and wider issues. Throughout the course of his career, this outward-facing and conversational aspect of his work was ever prominent and productive. Both these legacies yield massive potential for current theological thinking – resourcing not only historical enquiry but also constructive theology today.

Second, we as Editors were keen that the volume participate in the process of opening up Barth studies to fresh voices of enquiry. One can recognise the value of Barth’s work in all manner of ways without doing so uncritically, as if labouring under the assumption that Barth always has the final, definitive answer. Such an idea – and its associated defensiveness – would have Barth turning in his grave. In view of this, we were keen to feature in our work the contributions of a series of thinkers who seek to engage his views critically as well as to bring his work into dialogue with the challenges of today. In the course of his career, Barth himself was quite prepared to rip up the traditional dogmatic playbook in order to address the present with dynamic impact, even where that meant a self-imposed theological isolation. In the same way, we were keen to advance the idea that there is no magisterial reception of Barth.

PDJ: I concur with everything that Paul Nimmo says here, and would add that the high-quality of much recent work on Barth made editing the Handbook easier, as we could appeal to scores of terrific scholars, and intimidating, as we knew the standards for scholarship are higher than ever before.

I also would expand on the two points that Paul Nimmo has made. On one level, we very much wanted to present Barth as a dogmatician who puts a high premium on conversation. Sometimes that conversation is explicit, as when Barth engages early Christian writing, Aquinas, Calvin, Schleiermacher, etc.; sometimes the conversation is a bit more mediated (although no less important), as when Barth negotiates modern western philosophers, political theorists, and the like. I’d go so far as to suggest, in fact, that Barth has a fairly democratic sensibility as an author. While he is pretty clear about where he stands, he makes space in the Dogmatics with other peoples’ ideas, claims, fascinations, and the like. (The closest parallel in the twentieth century, on this front, might be William James – think of how many voices are present in The Varieties of Religious Experience! – but that’s a topic for another time.)

On another level, we were very eager to have conversation extended into the present, and to have scholars interrogate Barth from standpoints that he did not anticipate or could not have anticipated. Sometimes that led to a much-needed exposé of some of Barth’s blind-spots and failings – say, with respect to sex, gender, and race. But sometimes it opened up new points of valuable interaction – say, with respect to Barth’s relevance to environmental issues or the fact of religious pluralism.

All this, again, helps to offset a temptation that I know bedevils many of us: treating Barth as some kind of theological Marmite, worthy of outright adulation or blistering denunciation. Neither is helpful. Far better is a posture of hermeneutic respect, willing to embrace and think with Barth when it seems likely to push forward theological conversation, and willing to take leave of Barth when his voice needs to be moved into the background.

Can you briefly walk us through the three sections into which the Handbook is divided?

PDJ: The first section is a mini-intellectual biography and an exercise in historical contextualization. There are three historical pieces, followed by eight chapters that consider Barth’s intellectual conversation partners, stretching from the patristic and medieval periods, through the Reformation, and out into the complex world of European philosophy and politics. The second section is a comprehensive treatment of basic loci and themes in Barth’s thought: The Trinity, election, providence, theological anthropology, etc. The third section is titled “Thinking After Barth”; it sets Barth in conversation with a number of concerns engaged by contemporary thinkers.

PTN: Our hope is that the structure ends up being fairly intuitive for readers, allowing them to dip in where they need with a minimum of fuss. But we also hope that the arc of the volume – from history through tradition to construction – maps out for readers the way that theology should always proceed: properly grounded, but moving forwards, embracing critique and addressing the present. In that way also, it imitates Barth’s own procedure, never to rest content with existing answers, but always to strive afresh to hear the living Word of God in the world today and to respond to it with faith and obedience.

What are some of the advantages you both see for readers to have the Handbook available digitally in Logos?

PTN: For many years now, the Logos platform has distinguished itself as a go-to resource for work in biblical studies. But it has also progressively and deservedly attained an excellent reputation for being a platform on which intensive theological research can be undertaken. Having our Handbook available online will allow readers not only to have convenient access to the published chapters of our volume, but also to have powerful flexibility in terms of searching and cross-referencing terms and themes in a way that will facilitate scholarly work of the highest quality and rigour. We are delighted that Logos has agreed to make our Handbook available in this way.

PDJ: I don’t think I have much to add to that! As Paul Nimmo has said, the Logos platform is a great way for people to encounter a range of issues in the field of biblical studies, and I’m very pleased that Barth can become part of that broad conversation. More discussion – argument, agreement, disagreement, bewilderment, and the like – is always a good thing. “No boring theology!” as Barth once said.

Finally, which project(s) of yours should we look out for in the coming years that also deal with Karl Barth?

PDJ: I’m in the final stages of finishing a big, big book on patience – the first of two volumes, I hope. It’s not directly on Barth; it’s a constructive work. But there is lots and lots of Barth in there. And at some point in the next couple of years, I think I’m going to gather a bunch of articles and essays on Barth, most likely focused on the atonement, and shape them into a book. A book that is much shorter than the OUP Handbook, I hurry to add.

PTN: As I noted above, I am currently – at least, as and when the pandemic allows – finishing a new and long-planned book on Barth and the Lord’s Supper. The book has two main parts: the first is historical, tracing Barth’s evolving views of the Lord’s Supper over the course of his life and work, while the second is constructive, seeking to develop an account of the Lord’s Supper that would be true to Barth’s thinking in his final years. As is well known, he had hoped – but never managed – to write his doctrine of the Lord’s Supper for Church Dogmatics. Once that manuscript is completed, I hope to draw on Barth – though this time as one of a cast of many – in the course of a new project on sanctification … but that may be a little away.

The Oxford Handbook of Karl Barth is now available for pre-order on Logos, just one of a fantastic lineup of individual volumes from the Oxford University Press Handbooks series.

In addition, Logos is offering two exclusive collections of volumes from the OUP Handbook series, at special pre-order pricing:

The Oxford Handbooks Biblical Studies Collection (8 vols.)

The Oxford Handbooks Religion Collection (26 vols.)

Jump on these special offers now before the pre-order window closes, and take your study of Barth to the next level.