There are 211 instances of “the practice of communicating with a deity” in the Bible, according to the Logos Bible app‘s Factbook . Such a list demonstrates the massive undertaking that is the study of prayer. So, when we approach the topic of what happens when we pray, we must recognize the complexity and breadth of the topic. It is not the sort of theme one can exhaust in one blog post. To narrow our scope then, this post will survey some thoughts about how prayer relates to

- the inner life of God,

- our experiences,

- and the world around us.

Prayer and the inner life of God

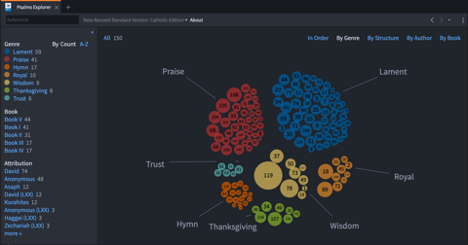

First, what happens to God when we pray? When we look at Scripture, there is a consistent expectation that God responds to prayer: actual communication is taking place. This contrasts sharply with other ancient Near Eastern and Greco-Roman prayers, which are often attempts by humanity to manipulate a deity into action. The biblical picture, generally speaking, is that prayer to YHWH should anticipate a response. The laments testify to this when they decry the absence of God’s answer, thereby indicating that such a response is rightfully expected. The Psalms Explorer in Logos classifies 59 of the 150 Psalms as Laments—almost 40 percent of the Psalter.

YHWH does not require manipulation to act, even if his actions seem beyond our comprehension. Jesus illustrates this truth in parables about the persistent widow (Luke 18:1–8) and friend at midnight (Luke 11:5–8). The point in both is that YHWH is not like the judge (Luke 18) or the sleeper (Luke 11).1

Leslie Hardin says in the Lexham Bible Dictionary article on prayer,

The biblical examples of prayer portray Yahweh as a God who listens, not a deity who is distant or must be cajoled into attending to the affairs of humanity. The earliest biblical prayers stem from a conversational intimacy with Yahweh and include spontaneous and unfiltered requests.2

By contrast, biblical prayers portray a God eager to listen to the concerns and cares of his people: “I call out to Yahweh; he answers me from his holy hill” (Ps 3:4).

Writes Karl-Friedrich Wiggerman, “Every theology of prayer presupposes a doctrine of God.”3 Consequently, our doctrine of God will heavily influence our theology of prayer. For example, suppose we hold to a strict view of the unchangeability of God.4 In that case, our theology of prayer will likely focus on what happens to us in prayer, since nothing can happen to God, per se.5 Thomas Aquinas gives the classic presentation of this view (ST II-II, q.83):

In prayer, man is not trying to force God’s will; he is submitting his desires to Him (this is inherent in the very idea of petition); and he does not pray in the hope of changing God’s mind but to cooperate with Him in bringing about certain effects which He has foreordained; prayer is a secondary cause, itself caused by God.6

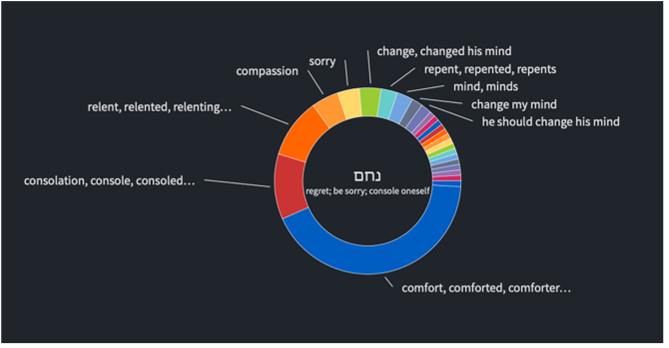

However, it is evident from Scripture that God can experience some change. If we consider the thirty-two passages where he is the subject of the verb נחם,7 we see that thirteen of them carry the impression of changing your mind (Exod 32:12, 14; Jer 4:28; 18:8; 26:3, 13, 19; 42:10; Joel 2:14; Amos 7:3, 6; Jonah 3:9, 10).

I find Eastern Orthodox theology quite helpful here, perhaps to the chagrin of many of my Western brethren.8 In it we find a distinction “between the essence of God, which they insist is unknowable, and what they call his energies, which are knowable.”9 What is the difference? “God is present to us through his energies (operational activity).”10 With this distinction between God’s essence (who God is) and energies (what God does), we can retain his unchangeability by locating it in his essence. He doesn’t change who he is. But his actions can vary so long as they meaningfully align with who he is. So much more could be said on this point, but as we’ve established already, there’s only so much we can do in one blog post. So for our purposes here, it is enough to say that our doctrine of God has huge implications for our doctrine of prayer.

Prayer and the life of man

But it’s not just our doctrine of God that informs how we understand prayer. Simon Chan says that “prayer is the first act that links doctrine to practice, and all the other exercises are simply elaborations of this primal act.”11 Prayer is connected to everything we do, think, believe, or experience. No doubt this is why Paul exhorts the Thessalonians to pray without ceasing (1 Thess 5:16–18; cf. also Phil 4:6). So what happens to us when we try to do that?

This is particularly challenging, not only because of varied perspectives on the matter. What occurs in us? Well, prayer is difficult, especially for those who have experienced divine hiddenness, the feeling that God is withdrawn, silent, or even absent in some sense. As Simon Chan says,

Intimacy with God is especially difficult because the faults are never mutual … When there is difficulty in our relationship with God, the fault always lies squarely with us. … [This] is especially hard when each time we face an impasse, a dry stretch, a deathly silence, we discover something within ourselves causing the problem.12

That hurts. We want some vindication in our pain, especially when we are not the cause of it. But “we are never given the satisfaction of being able to turn to God and say smugly, ‘I am right this time.’”13

I want to be careful here to clarify that I’m not suggesting that our suffering is all our fault. The world is often a horrible place where horrible things happen. Virtually every Christian tradition throughout history has affirmed that God is not the author of these events, even while maintaining some version of his providential sovereignty over them.14 If he is not the cause, then the responsibility is either ours or that of the fallen world around us.15 Since he is not the cause, God is under no obligation to restrain any evil from us.

But even when we know that to be true, we often do not feel like it is. Like any relationship, it’s vital that communication continue even through strife and frustration. Often, we must join the psalmist and lament the inscrutable nature of the horrors in this world—and our perception of God’s inaction.16 And just like with the psalmist, these complaints count as worship! So, when we’re disappointed with God, it’s important that we join the long history of believers who have told him so. We do so, knowing he’s not in the wrong, even when we feel like he is. We must make the decision to continue our communication, even when we are upset with the One to whom we communicate. We aren’t always going to know why things happen or why it feels like God is absent. Like any relationship, there are natural seasons, and we need to trust God through them.17

This is a profoundly challenging topic to discuss, and at some point we do have to yield to mystery. In those spaces, we lean on what we know, what we believe, and what we’ve experienced. Based on these things, we have a decision to make. As we face uncertainty, frustration, and divine silence, do we abandon our faith or press forward into the mystery? Audrey Assad wrote a song based on Mother Theresa’s journals. It illustrates both this tension and her decision to press forward at every turn to find Jesus. It opens with the following:

Jesus, I need You; lover, don’t leave

Did You call my name

Just to plunge me deep into the darkness?

Do You know that I can’t even hear Your voice?

As the song progresses, she seems to chase Jesus as he moves away.

So I reach out my hands to find You where You have been hiding

Maybe I’ll see You deep in the eyes of the dying

The silence continues, as does the despair, but her response remains the same.

So I move closer to plague and disease and disorder

Maybe I’ll hold You in the beggars and thieves that You died for

As the song begins to close, she pleads with him to stay, bargaining that she’ll rejoice in suffering if he stays with her. And as it closes, her response remains the same.

I look to the hills, I lift up my eyes to the heavens

Maybe I’ll see You flickering on the horizon

There’s true desperation here, but there is also determination and hope. Paul wrote about a similar desperation to know Jesus in the power of his resurrection and the fellowship of his sufferings (Phil 3:10). This is the union offered to us in prayer. And while power sounds great, resurrection power is useless until something dies.

So, what happens when we pray? We change. “To pray is to change. Prayer is the central avenue God uses to transform us.”18 We’re conformed more and more to the image of the Son (Rom 8:29). This is the same Son who felt abandoned by God (Matt 27:46, cf. Ps 22:1–2), sweat blood in anguish (Luke 22:44), and mourned the loss of a friend (John 11:35). Conformity to his image is not always comforting or safe, but like Aslan, it’s always good. Prayer, then, isn’t an attempt to control or manipulate God. It’s a God-given miracle and grace of union with him, even when that union does not feel the way we want. Sometimes union might feel like separation. Sometimes it feels like suffering and death. But on the other side of that suffering and death, we are promised the hope of resurrection through that union. Suffering, death, and separation don’t win.

My dark night

I found comfort in Audrey’s song in my dark night of the soul. It reminded me not to give up, even when I don’t see what’s happening. Instead, I pushed forward. I kept pushing. I kept loving. I kept serving.

Eventually, prayer transitions toward silence.19 Chan very helpfully illustrates this progression through the analogy of a marriage.20 At first, the relationship is easy. But ultimately,

Romance gives way to reality in a period of painful discoveries and adjustments … It is unfortunate that many modern Christians are never taught such elementary lessons of spiritual progress. They expect their early excitement to continue uninterrupted throughout life. The end of the honeymoon disturbs them, and they seek desperately to rekindle their first flush of feeling. But the great spiritual writers are quite unanimous that this is a basic part of growth.21

So, prayer grows us. It conforms us, albeit sometimes uncomfortably, to the image of God’s Son. Prayer also moves the heart of God. Does it do anything else?

Prayer and the life of the world

Indeed, it does. I’ve suggested already that God experiences change, though not in his nature. I’ve also suggested that we are changed as well. But prayer involves more than just us and God. It involves the entire world. So, if I’m right on the first two points, then it logically follows that our prayers to God might move him to change things in the world around us. This is a hard line to walk because he does not always change things, and when he does it isn’t always in the way we want. But just as the laments of the Psalms cry out to God because the psalmists expect his response, we ought to pray expecting the same. We may find ourselves joining in lament for a time, even for a long time. But that does not mean that God is inactive nor that he does not intend to respond. Keep praying. Keep looking for the flickering on the horizon.

***

Recommended reading

Abandonment to Divine Providence: The Classic Text with a Spiritual Commentary by Dennis Billy, C.Ss.R.

Regular price: $13.99

Spiritual Disciplines Handbook: Practices That Transform Us, rev. ed.

Regular price: $19.99

- “Rather than recommending continual petitioning of God until He grants our requests, this parable demonstrates that God is not like the judge. Unlike the judge, God ‘will see that they get justice, and quickly’ (Luke 18:8). The parable of the Friend Knocking at Midnight (Luke 11:5–8) has the same effect, for petitioners do not have to keep knocking to get God’s attention.” Leslie T. Hardin, “Prayer,” in The Lexham Bible Dictionary, ed. John D. Barry et al. (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016).

- Hardin, “Prayer.”

- Karl-Friedrich Wiggermann, “Prayer: Dogmatic Aspects,” in The Encyclopedia of Christianity, ed. Erwin Fahlbusch et al.(Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2005), 326.

- This idea has plenty of scriptural and historical warrant. See the Logos Factbook on Immutability.

- Richard Foster suggests that such a perspective is closer to Stoicism than Christianity. “Many people who emphasize acquiescence and resignation to the way things are as ‘the will of God’ are actually closer to Epictetus than to Christ.” Richard J. Foster, Celebration of Discipline: The Path to Spiritual Growth, 20th anniv. ed. (San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 1998), 35.

- Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church , s.v. “prayer.”

- It’s worth noting that this post will follow the conventions laid out in the Bible for divine pronouns. This doesn’t suggest that God is male any more than female. God transcends gender. But for the sake of readable prose, pronouns are necessary, and masculine pronouns are used in Scripture.

- Adherents of classical theism, in particular, will likely part ways with me over what I will say in this paragraph. However, I think the overall idea is much the same in their view. God remains unchanged, even if, from our limited perspective, he may seem to change in some way. I find the Eastern Orthodox distinction of essence/energies incredibly helpful in explaining this ostensible paradox. For more on classical theism and the Trinity, see Matthew Barrett’s Simply Trinity.

- Donald Fairbairn, Eastern Orthodoxy through Western Eyes, 1st ed. (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2002), 54–55. For an excellent summary of this view from a Western and Protestant perspective, see chapter 4 of this work.

- Fairbairn, Eastern Orthodoxy, 54, quoting Aghiorgoussis in Fotios K. Litsas, Companion to the Greek Orthodox Church (Greek Orthodox Archidioce, 1988), 157. Gregory Palamas eventually makes this distinction quite clear, but it is definitely present in Dionysius. Andrew Louth, “Byzantine Theology Part 2,” Timeline Theological Videos, May 7, 2015, YouTube video, 00:06:56, https://youtu.be/J8OyR__AA88. See also Fairbairn, Eastern Orthodoxy through Western Eyes, 54; and James R. Payton, Light from the Christian East: An Introduction to the Orthodox Tradition (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press Academic, 2007), 78–82.

- Simon Chan, Spiritual Theology: A Systematic Study of the Christian Life (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1998), 125.

- Chan, Spiritual Theology, 132.

- Chan, Spiritual Theology, 132.

- The issues surrounding this tension are well outside this essay’s scope. A helpful summary can be found at Dennis W. Jowers, ed., Four Views on Divine Providence (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2011).

- The latter includes all creation, which extends to angelic and demonic forces.

- For more on responding specifically to the horrific in life, see Scott Harrower’s excellent God of All Comfort: A Trinitarian Response to the Horrors of This World (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2019).

- For more on these seasons, see Jean Pierre de Caussade, The Sacrament of the Present Moment, reissue ed. (San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 2009); John of the Cross’ Dark Night of the Soul & Ascent of Mount Carmel; and Brother Lawrence’s The Practice of the Presence of God. See also Chan, Spiritual Theology, 133–37.

- Foster, Celebration of Discipline, 33.

- Cf. Chan, Spiritual Theology, 133–34; Jean-Nicolas Grou, How to Pray, trans. Joseph Dalby (Cambridge: Lutterworth Press, 2008); John Anthony McGuckin, The Westminster Handbook to Patristic Theology (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2004), 23. At this point, some Pentecostals, myself included, would say that glossolalia is particularly useful, as it is “the means by which one participates in trans-rational communication with God, communication that conveys mysteries to God (1 Cor 14:2) while simultaneously building up the speaker. Since this communication lacks propositional content, it is apophatic by nature. It transcends both affirmations and negations.” Ryan Lytton, “Is Wisdom Silent?: Apophatic Glossolalia,” Spiritus: ORU Journal of Theology 7, no. 1 (March 7, 2022): 35–52.

- Chan, Spiritual Theology, 133–35.

- Chan, Spiritual Theology, 134–35.