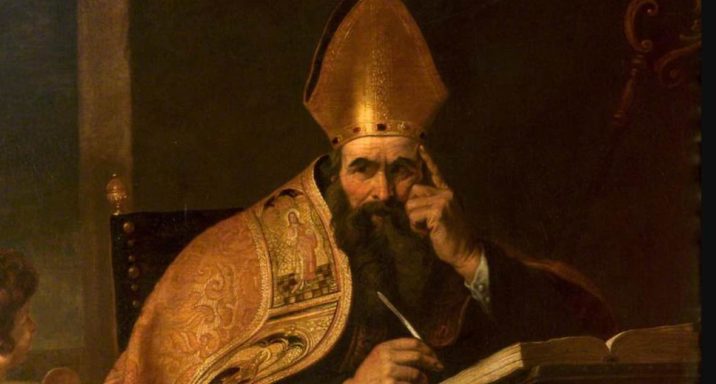

One of the most important figures of the Reformation died over a millennium before Luther was even born. B. B. Warfield explains his significance:

It is Augustine who gave us the Reformation. For the Reformation, inwardly considered, was just the ultimate triumph of Augustine’s doctrine of grace over Augustine’s doctrine of the Church. (The Works of Benjamin B. Warfield, IV:130)

As Warfield also points out, everybody wants to claim Augustine—and because he wrote so voluminously and went through certain theological evolutions, many people can. We can find apparent endorsements for many theological ideas in Augustine, ideas which today have formed ecclesiastical camps.

I want to claim him, too—to find support for the evangelical doctrine of scriptural inerrancy. Augustine may say other things that qualify (or contradict—he wasn’t himself inerrant) what I’m about to quote. But I find it striking that he says some of the same basic, major things about the Bible that evangelicals say today about it. Here are three of them.

1. Augustine refuses to blame the Bible for apparent errors in the Bible.

He writes,

I have learned to yield this respect and honour only to the canonical books of Scripture: of these alone do I most firmly believe that the authors were completely free from error. And if in these writings I am perplexed by anything which appears to me opposed to truth, I do not hesitate to suppose that either the [manuscript] is faulty, or the translator has not caught the meaning of what was said, or I myself have failed to understand it. (Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, 1:350)

This is what evangelicals do today: if we come across an apparent error or tension in the Bible, we check for textual errors or translation difficulties, and we are prepared to blame our own (fallen, finite) powers of understanding before blaming the Bible.

Nonetheless, there’s a ditch in the appeal to textual criticism (a ditch evangelicals still warn about today): Augustine complains about readers who try to wriggle out from under what the Bible is saying by claiming textual corruption:

When these men are beset by clear testimonies of Scripture, and cannot escape from their grasp, they declare that the passage is spurious. The declaration only shows their aversion to the truth, and their obstinacy in error. Unable to answer these statements of Scripture, they deny their genuineness. (Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, 4:178)

Professing Christians don’t usually use this strategy, but cultic groups do. To this day some of them say that the Bible has been purposefully altered over the centuries. Augustine answered their charge back when my ancestors were Celtic tribesmen.

2. Augustine makes the Bible the standard by which truth is judged.

The basic, intuitive argument for biblical inerrancy has always been that the Bible is God speaking and that God cannot lie. If you admit one error in Scripture, Scripture can no longer be the judge of truth. Perhaps (metaphor alert) not everyone who steps onto this slippery slope lets the whole camel into the tent, but they’re skating on thin ice. So evangelicals generally say.

Augustine, in my judgment, makes the same slippery-slope-camel-in-tent-thin-ice argument. It was not invented by B.B. Warfield and the Princetonians in the 19th century:

It is one thing to reject the books themselves, and to profess no regard for their authority… and it is another thing to say, This holy man wrote only the truth, and this is his epistle, but some verses are his, and some are not. And then, when you are asked for a proof, instead of referring to more correct or more ancient manuscripts, or to a greater number, or to the original text, your reply is, This verse is his, because it makes for me; and this is not his, because it is against me. (Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, 4:178)

Throughout this paragraph, Augustine implies that the original writings of the apostles, accessed through our best efforts at textual criticism (when necessary), are the standard by which truth is judged. He is well aware, all those centuries ago, of the human tendency to try to make the Bible into a wax nose, and he won’t have it.

3. Augustine uses the slippery slope argument for biblical authority.

Augustine openly names the main alternative authority that tends to arise if Scripture loses its rightful spot: me.

Are you, then, the rule of truth? Can nothing be true that is against you? But what answer could you give to an opponent as insane as yourself, if he confronts you by saying, The passage in your favor is spurious, and that against you is genuine? (Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, 4:178)

Either God is in charge, or people are. Either we are creatures subject to the Creator’s stated norms, or we are autonomous, making our own norms. But if I get to be autonomous, so does the next guy. We have no common ground of truth to stand on. We lose our religion by losing our ability to appeal to a standard we both acknowledge.

Human books can be great—Augustine wrote a lot of them—but they cannot compel belief and obedience.

In the innumerable books that have been written latterly we may sometimes find the same truth as in Scripture, but there is not the same authority. Scripture has a sacredness peculiar to itself. In other books the reader may form his own opinion, and perhaps, from not understanding the writer, may differ from him, and may pronounce in favor of what pleases him, or against what he dislikes. In such cases, a man is at liberty to withhold his belief, unless there is some clear demonstration or some canonical authority to show that the doctrine or statement either must or may be true. (Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, 4:180)

Human books are not the ultimate authority in the Christian church or conscience. They can’t be. Here is something that sounds very like the Reformation’s sola scriptura:

In consequence of the distinctive peculiarity of the sacred writings, we are bound to receive as true whatever the canon shows to have been said by even one prophet, or apostle, or evangelist. Otherwise, not a single page will be left for the guidance of human fallibility, if contempt for the wholesome authority of the canonical books either puts an end to that authority altogether, or involves it in hopeless confusion. (Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, 4:180)

Others might find competing themes in his writings—I am not an Augustine expert by any means. But the Augustine we find in these passages teaches (as someone whom I respect once said) that any decision to distrust God’s words is a decision to trust someone else’s. This is the slippery slope argument for inerrancy, delivered circa the fall of the Roman Empire.

***