Lexicons are commonly used for studying biblical languages. It may shock you, then, that I discourage beginning Hebrew and Greek students from using them. I’m not kidding.

I’d be happy if beginning students never used them.

I don’t diminish lexicons because they are so frequently abused, though that’s true. It also isn’t because I want people to spend hundreds of hours memorizing Hebrew and Greek vocabulary. The reason is that, for those newly initiated to Hebrew and Greek, lexicons just don’t give you much useful information.

Basically, all standard lexicons do is give you alternative English glosses. And yet professors seem bent on the idea that they are indispensable for beginning students.

What’s a lexicon anyway?

A lexicon is a book that lists each word found in a given body of literature in a particular foreign language, and assigns an English equivalent to each word. The better lexicons go beyond that service and list several English equivalents and catalog specific instances of that word in the literature where that word occurs. This informs the user that the given word could be used in many contexts, and it also provides examples.

But if we’re honest, all of this only enables translation and reading—not interpretation. Your teenager knows how to read the English Bible. Do you really presume that just because they can read they are prepared for interpretation? I didn’t think so.

Reading and interpretation are related, but they aren’t the same thing.

Why not just use an English thesaurus?

Lexicons put data in front of you and misleadingly suggest a one-to-one correspondence of each word with an English word. If you think about it, that’s basically what an English thesaurus does for English. You start with one word and then are given a list of other words that you might want to swap in for the word you started with.

Thesauruses are often used the way beginning students use lexicons. If I wanted to know what the word “beginning” might really mean in that last sentence, I could go to a thesaurus and discover that “beginning” might “mean” the following:

- birth

- commencement

- onset

- opening

- inception

- source

- emergence

- rising

- dawning

- simplest

- initiatory

- introductory

You could argue for a couple of those as to what was intended, and then you’d pick one. Never mind that each of those synonyms has its own range of nuances; never mind that this method makes the user the point of origin for “meaning,” as opposed to the context.

The latter requires time reading through the spectrum of a word’s usages and then—most importantly—thinking carefully about how the context allows or rules out certain meanings. That’s the process of tracing the thought of the text and its author in an effort to describe what his point is in as many words as it takes.

That goes well beyond looking for one-word substitutes. Discovering word substitutes is what standard lexicons do for you.

That isn’t word study.

Reading is not exegesis

Why do we think that the enterprise of looking up a Greek or Hebrew word to get an English equivalent is a useful thing to do? Professors would answer, “So you can do translation.” We now have hundreds of English translations, so why would we need to do our own? The truth is that knowing thousands of English word equivalents for Hebrew and Greek never made anyone a more careful interpreter. Being able to sight read Greek or Hebrew doesn’t guarantee exegetical accuracy any more than being able to read your English Bible does.

Illustrating the problem

You might think I’m exaggerating a bit. Let me demonstrate.

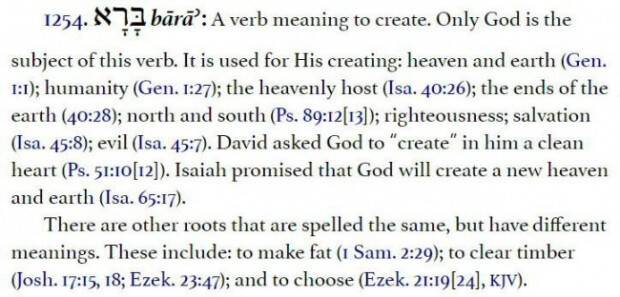

Below is the entry from The Complete Word Study Dictionary: Old Testament for the Hebrew word baraʾ, the word translated “create” in Gen 1:1.

So what did we learn? That the Hebrew word baraʾ means “create” in many instances, and that God is always its subject. We’d already know the former if we were using an interlinear, and the fact that God is the only subject of that verb is interesting, but it tells us nothing about what baraʾ means.

Are you more able to interpret the passage? Did your congregation learn anything when you told them that behind the English word “create” is a Hebrew word that means “create”? What kind of creating are we talking about? Does the word ever refer to using materials? Does it always mean creation from nothing? Does it have synonyms that describe the use of materials? How do I find them? What are the verb’s objects, the things created? Why would an author use this verb and not another one? Does an author ever use this verb along with another one in parallel?

The lexicon doesn’t tell us.

More importantly, the lexicon never suggests that we should even ask those questions. It just gives us an English equivalent and then becomes mute.

Maybe the problem is that I used The Complete Word Study Dictionary: Old Testament. Perhaps if I used a scholarly lexicon the floodgates of insight would open.

Nope.

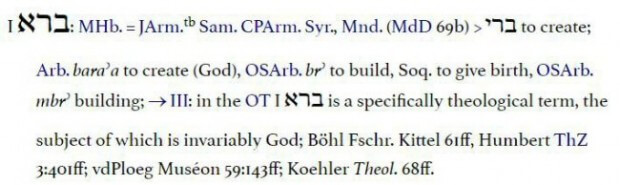

The entry below is from the leading scholarly lexicon for biblical Hebrew, The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament (HALOT):

What did we learn this time? That baraʾ means “create”—just like our English translation tells us. We learned that some other Semitic languages have a verb for “create” as well (really, does any language not have such a word?). The rest of the HALOT entry divides the occurrences of the Hebrew verb baraʾ into something in Hebrew grammar known as stems. Depending on the verb, that can be very important, since translation of a word can depend on the stem. But many beginners aren’t going to know about stems, and in the case of baraʾ, even if they did it wouldn’t be useful. The Hebrew verb baraʾ occurs in two stems: In the “Qal” stem the verb means “to create”; in the “Niphal” stem, which is passive, the verb means “be created.”

Wow. That’ll preach.

An antidote

So how can you do better word studies if you’re not a specialist in Hebrew or Greek? There are three truly indispensable things you need for developing skill in handling the Word of God.

First, you need a means to get at all the data of the text. Logos Bible Software is the premier tool for that. Through reverse interlinears, you can begin with English and mine the Bible for all occurrences of a Greek or Hebrew word. Logos 6 then takes that data and renders it in a variety of visual displays and reports—such as the Bible Word Study report, where you see how your word relates grammatically to other words in the sentence—so you can begin to look at the material and think about it from different angles.

Second, you need someone who is experienced in interpretation to guide you in how to process the data in front of you. There is simply no substitute in word study for thinking about the occurrences of a word on your own, and so you need training in what questions to ask and why to ask them. Lexicons will give you lists of English choices, but cherry-picking a list isn’t the same thing as asking critical, reflective, interpretive questions about the word in its context.

Third, you need practice, practice, and more practice.

Logos Bible Software has been helping you do the first of these steps for years. Moving your Bible study beyond perusing a list of English words is precisely why Logos has made a commitment to the second step, by producing over 20 hours of guidance in our Learn to Use Biblical Greek and Hebrew Mobile Ed courses. These courses, which go beyond mere video, are our first step toward helping you understand how to think about words and grammatical concepts so you can begin to discern the nuances of Greek and Hebrew for interpretation. It’s time to learn how to handle the biblical text, not just read English words in a lexicon.

You’re smarter than that.

Order Learn to Use Biblical Greek and Hebrew today!

Michael Heiser earned his PhD in Hebrew Bible and Semitic languages from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He also holds degrees from the University of Pennsylvania and Bob Jones University.