What is the most violated verse on the internet? Probably, “Love the Lord your God with all your heart.” Every online sin draws its nourishment from that root.

But right behind that violated verse might be—our second-place winner—Paul’s words: “Speaking the truth in love” (Eph 4:15).

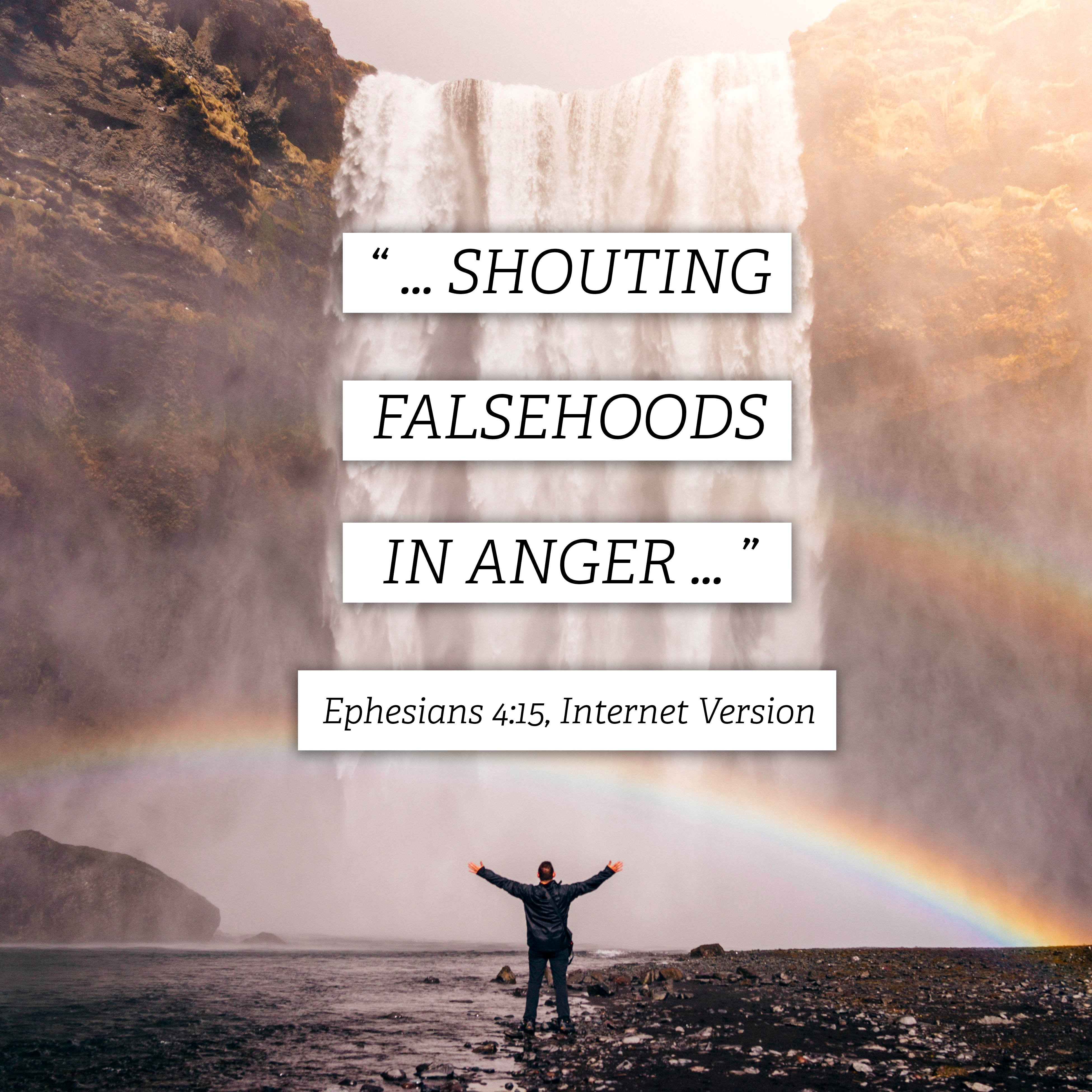

People online don’t have a great reputation for speaking the truth. And even when they do it, it’s just as likely to be spoken in disdain as in love. The internet version of Ephesians 4:15 might be, “Shouting falsehoods in anger.” How’s that for a shareable meme?

Warning: you’re on the internet right now. Its gravity is pulling you. You need to spend the next few minutes reflecting on what it means to “speak the truth in love.”

What does it mean to speak the truth in love?

“Speaking the truth in love” is a phrase Paul uses in his letter to the church at Ephesus. It’s part of a list of things that are meant to flow from one particular action of the risen Christ; namely, his decision to give “apostles, prophets, evangelists, pastors, and teachers” to his church.

He did this, Paul explains, “to equip the saints for the work of ministry.” And this, in turn, will “build up the body of Christ,” Paul says. And once that body reaches “maturity,” it won’t be gullible like children; it won’t be “carried around by every wind of doctrine.”

Instead, it will find itself “speaking the truth in love.”

This will happen.

And this is the context for Paul’s famous phrase. It’s not as if “speaking the truth in love” is unnecessary outside church; no, as I said, we could sure use some more of it on the internet. But Paul’s original intent was not to make a general statement about the way all humans should behave, but to describe what actually will happen when the body of Christ is functioning properly underneath its Head.

Is “speaking the truth in love” what’s happening through you at your own church, and among Christians you connect with in other venues? How can you encourage the growth of this practice in yourself and in your church?

We’ll get there.

Some Bible nerd questions

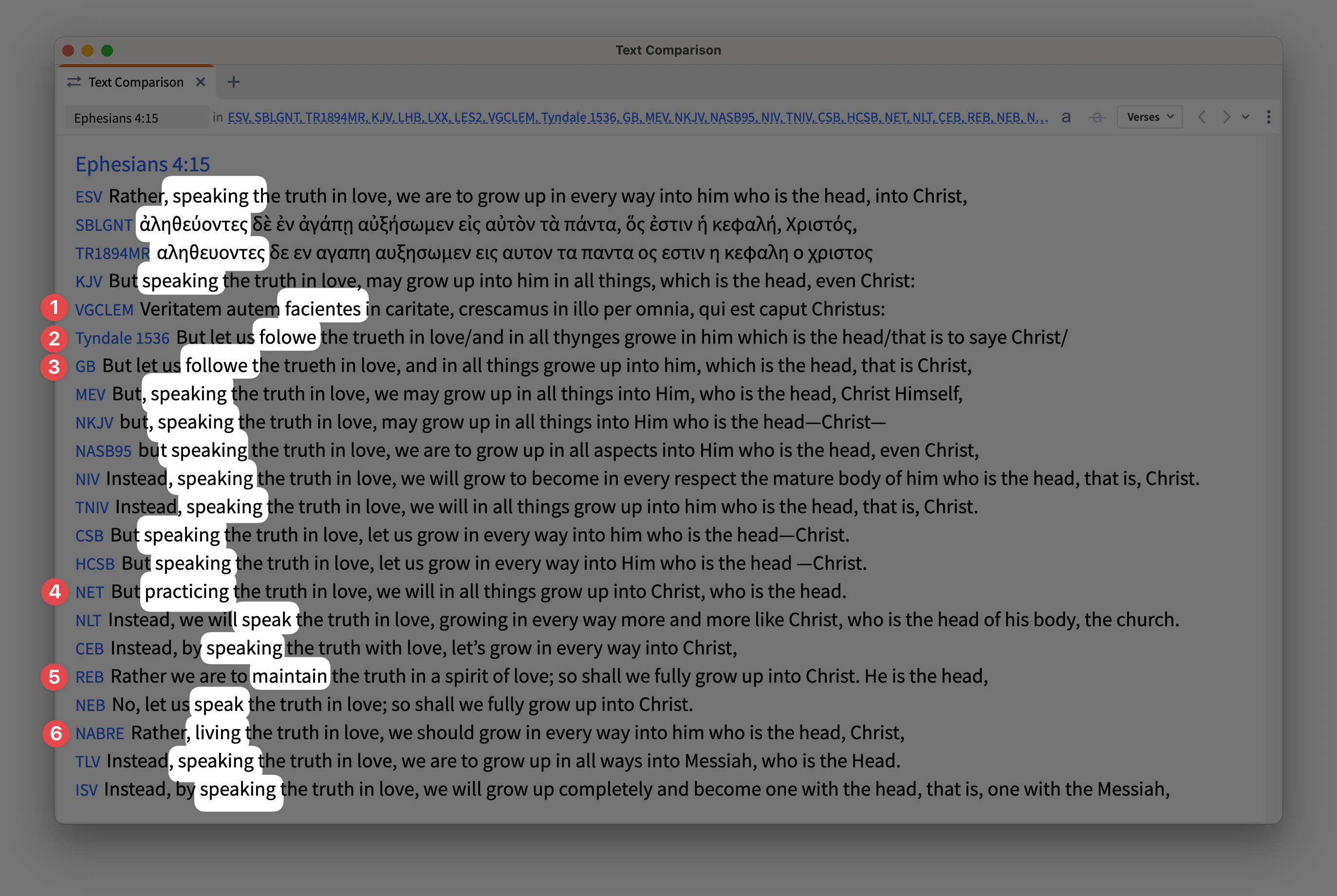

But first—it’s time to get Bible nerdy for a second. I habitually check multiple Bible translations whenever I study a verse. Here’s the Text Comparison Tool in the Logos Bible Study app at Ephesians 4:15, featuring all the Bibles I normally check. Look how they translate the key verb:

I noticed a little something—did you see it? (I kinda drew attention to it.) The Tyndale New Testament of 1526 had, “Follow the truth,” not, “Speak the truth.” In cases like this, in which a pre-KJV translation differs from the KJV in some minor particular, I often find that the older translation matches the Latin Vulgate. And indeed here it does. Facientes is from facere, the root of our “manufacture.” It means “doing”—“doing the truth,” not “speaking the truth.”

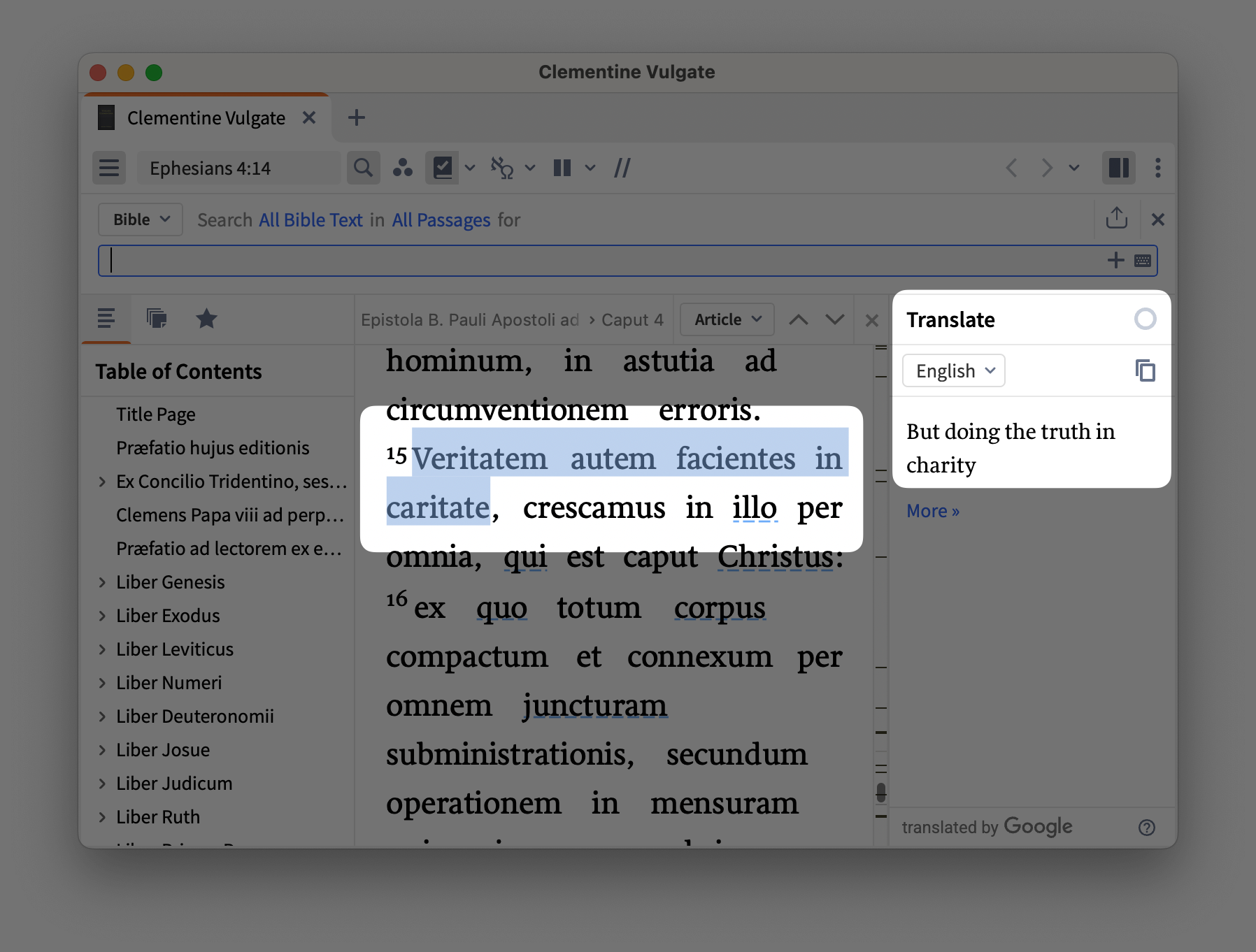

If checking the Latin Vulgate feels beyond you, it need not. I used Logos 10’s Translation tool to check up on my own rusty Latin—it’s as easy as highlighting some text and clicking an icon:

European Christians for many centuries have read “doing the truth” here in Ephesians 4:15.

Five other translations in my standard list also went with something other than “speaking.” They had Christians “practicing,” “maintaining,” “living,” and “following” the truth.

When you see minor variation in Bible translations like this, I think you should not assume that one rendering is right and the others are wrong. I think you should assume that the many translators involved had good reasons for their choices. And indeed, here the verb the Spirit chose in Greek is genuinely ambiguous. The word could focus on verbal communication (“speaking the truth”), or it could focus on ethical action (“practicing the truth”).

The NET Bible notes are frequently an excellent tool for tracking down questions about Bible translation. They defend ably the minority view among modern translators. They point out uses of the word in the Old Testament1 in which the word means “practicing the truth.”

But I tend to side with the majority view, ably represented by S. M. Baugh’s excellent Ephesians commentary in the Evangelical Exegetical series. He points to the other use of the word in the New Testament, and he notes that “the contrast with deceit and lies in v. 14 makes ‘speaking’ or ‘telling’ the truth the best meaning.”

Bible nerdiness complete. Let’s move to application.

How do you speak the truth in love?

The part of Ephesians 4 in which these words appear is written in the indicative mood: even fourth graders who have paid attention in English class should be able to see that Paul chose declarative sentences in the paragraph we’re looking at. But then this paragraph comes right after Paul’s famous switch to the imperative in Ephesians 4:1: “I therefore, a prisoner for the Lord, urge you to walk in a manner worthy of the calling to which you have been called.” So, as is often the case with the ethical commands of the New Testament, “speaking the truth in love” is something that will happen, because Christ, the Lord of the church, has ordained that it be so—and it is something that must happen, because we are called to obedience to Christ’s purpose.

Now, my lived experience as a Christian suggests to me that “speaking truth in love” wouldn’t have to be in any way a command for us, or an expectation, if it didn’t have something to do with telling other Christian people truths about their sin that they probably don’t want to hear. That’s why the hardest question about how to apply these words—how to use these words faithfully and obediently—is more the when and not the how. When do you confront another Christian, and when do you refrain?

But I think it’s important to recognize first that Paul isn’t actually drawing a contrast in this passage between “speaking the truth in love” vs. “speaking the truth with a bad temper,” or “speaking the truth in love” vs. “failing to speak up when you see another Christian sinning.” His contrast is between the cunning, crafty, and deceitful words of false teachers and the honest, straightforward, loving words Christians should speak to each other.

If, on occasion, these words must include some kind of rebuke, it sure helps if the rebuker already has a pattern of speaking other truths in love.

But I am writing to an internet audience who very likely rode the Google wave here because you are anticipating having to confront another professing Christian’s sin. “Speaking the truth in love” feels like a very scary prospect at the moment. You’re wanting to make sure it means what it sure seems to mean. Is it really your job to tell other Christians that you saw them being divisive or angry or gossipy or indiscreet? Is it really God’s call on you to speak the truth to your sister about her disrespect toward Mom? Would it spoil some vast, eternal plan if somebody else took this plum job?

That’s where love comes in. If you love someone, that will go a long way toward making your words of rebuke palatable. Be driven by love, not fear. If you love a fellow Christian, this will drive you to care more about the negative effects their sin has on them than the negative effects their poor reaction might have on you. If you love your brother, this will lead you to carefully feel your eyeballs for beams before you engage in a mote intervention. Love will bring questions before bringing accusations. Love will cover a multitude of other little sins so that the focus can remain on what’s truly serious.

And note that Paul didn’t say, “Speaking the truth in love and thereby guaranteeing a favorable response.” As with the gospel, so with any truth: you can’t control whether another heart will receive it.

Go and speak some more

I design church websites on the side, and I’ve done it for well over a decade now in my free time. So I have on many occasions pored over two hundred smartphone photos of this or that random small church. With apologies to all my wonderful clients, not once has any of the pictures revealed a stock-photo-worthy collection of exceptionally attractive, perfectly coiffed people, all smiling ecstatically while both enjoying and spreading Christian love.

I’m not saying the church people of Random Baptist Church are unhappy. I’m not saying they’ve all been uglified. I’m saying that not many people of power and of noble birth are called. Most church people look like average Americans—except more so. I often think to myself, Church ministry is not all about fame and self-fulfillment; it’s regular people in unexciting places doing often slow and tedious things. Living in love with the other Christians who actually attend your real-live church will not always be fun and will win you no public awards.

But “speaking the truth in love” is an essential descriptor of what goes on in church, even if the people in your church don’t make it particularly easy. It’s part of an overall pattern in Ephesians 4:15, a pattern of mutual edification that draws from the equipping ministry of faithful church leaders—that, in turn, derives from the gracious gifts of Christ himself. Christ is the source, and he is the goal: “speaking the truth in love” is supposed to lead to us “grow[ing] up in every way into him.”

Take these simple thoughts to church with you next Sunday. See if they don’t invest that day with a significance you forgot was there.