Greek New Testament manuscripts often use paragraphs to indicate a shift in thought. But modern editors have not felt bound by these paragraph divisions: each Bible text may have its own.

Paragraphing is a necessary task for translation—and a help for interpretation. In my last twenty-four hours of Bible reading and preaching, I came across two separate places where paragraphing helped me ask interpretive questions—and achieve interpretive insights—I wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Come to Me

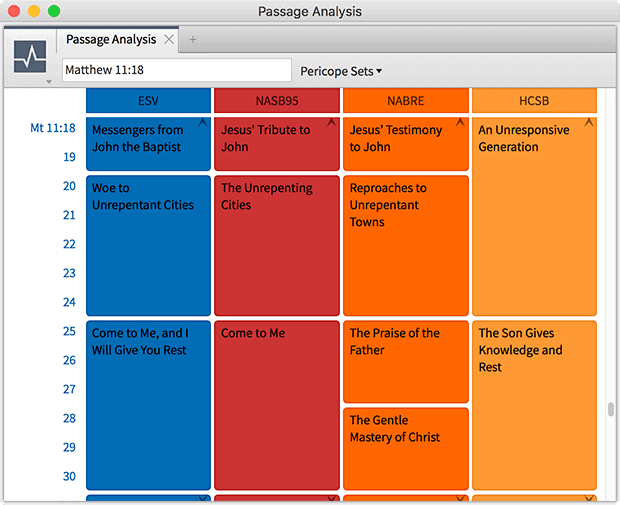

In Matthew 11:28, Jesus speaks the famous and treasured words, “Come to me, all who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest.” Some Bible editions start a new paragraph before these words; some don’t. Every translation has to make a decision with no direct evidence from Matthew’s pen. We don’t know whether Matthew put a break there because we don’t have his original manuscript. You can see the paragraph divisions chosen by various translations (ESV, NASB95, NABRE, and HCSB) in the Logos Passage Analysis tool, and they clearly don’t all agree:

As I was preparing a message on this passage, I noticed this disagreement for the first time. Here’s the whole paragraph in the ESV (vv. 25–30):

At that time Jesus declared, “I thank you, Father, Lord of heaven and earth, that you have hidden these things from the wise and understanding and revealed them to little children; yes, Father, for such was your gracious will. All things have been handed over to me by my Father, and no one knows the Son except the Father, and no one knows the Father except the Son and anyone to whom the Son chooses to reveal him. Come to me, all who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me, for I am gentle and lowly in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light.”

The ESV editors decided to make this one paragraph instead of two, which forced me to ask, “What does ‘Come to me, all who labor’ have to do with what Jesus said right before?” The answer was not immediately obvious to me.

So I did what the famous philosopher Winnie the Pooh does: think, think, think. I expended neuronal energy. And I prayed for wisdom. And then I pulled up my saved “Matthew” layout in Logos—some Bible texts and my favorite Matthew commentaries—and read what others had to say.

The most persuasive and helpful answer I found was in Blomberg’s NAC volume. Once he described the thought progression for me, I could see it for myself. It was there all along. Other commentators (such as France in the NICNT) come to similar conclusions: the paragraph belongs together because in it Jesus states God’s prerogative to use his Son to reveal himself to mankind—and then Jesus goes on to do the revealing.

The invitation “Come to me” is best understood as Jesus doing what he just said it was his right to do: choose to reveal the Father. If you see him, you see the Father (John 14:9); if you come to him, you come to the Father. A stringent statement of divine election is followed by an indiscriminate call: all who labor and are heavy laden are invited. The one requirement Christ mentions, other than coming, is his light and easy yoke.

Cast not your pearls before swine

The very same kind of thing happened to me in a different translation during my Bible reading this morning. I was reading the Sermon on the Mount in the CSB, and I saw this paragraph:

Do not judge, so that you won’t be judged. For you will be judged by the same standard with which you judge others, and you will be measured by the same measure you use. Why do you look at the splinter in your brother’s eye but don’t notice the beam of wood in your own eye? Or how can you say to your brother, “Let me take the splinter out of your eye,” and look, there’s a beam of wood in your own eye? Hypocrite! First take the beam of wood out of your eye, and then you will see clearly to take the splinter out of your brother’s eye. Don’t give what is holy to dogs or toss your pearls before pigs, or they will trample them under their feet, turn, and tear you to pieces. (Matt 7:1–6)

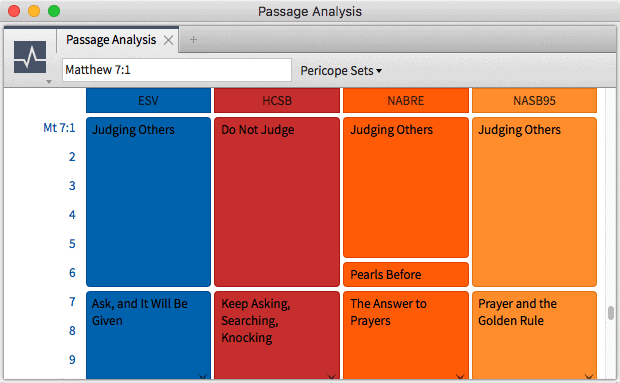

I always intuitively put a paragraph break in there—can you guess where? The (Roman Catholic) New American Bible will show you:

I have tended to read Jesus’ warning against tossing pearls to pigs—and isn’t that a vivid picture?—as a separate, standalone proverb. And the NAB marked it the same way. It gets a separate heading in their text. Editors of this translation are guiding readers to read it a certain way. But editors of the ESV, HCSB, and NASB keep verse 6 as part of the “Judging others” paragraph (will evangelicals and Catholics ever agree?).

I noticed this disagreement. Once again I thought. Once again I prayed. Once again I had trouble coming up with an answer. Was Jesus saying that you shouldn’t even bother approaching foolish people about splinters in their eyes? I wasn’t sure. Once again I sought help from gifted teachers.

The first one I read, Blomberg (NAC), made me feel better about the difficulty I felt:

Verse 6 seems cryptic and unconnected to the immediate context, but it probably further qualifies the command against judging. (128)

The ultimate judgment of someone else’s soul is not up to me—and for this I am grateful. But I must make proximate judgments all the time: I can’t keep up relationships with everybody, and I can’t keep making appeals to every enemy who has written me off, or every person who likes the splinter in his eye. Sometimes it is right to move on.

Seeing this statement about pearls and pigs in the same paragraph as Jesus’ famous “Judge not” comment (the most popular verse in America) lends support to the standard evangelical interpretation of this passage. Jesus doesn’t condemn all “judging” outright. Instead he insists that we use only those measures of judgment that we are willing to have used on ourselves. In other words, what is good for the goose is good for the gander—but not for pigs or dogs. Jesus allows me to “judge” that someone will never listen. As Blomberg says, “One must try to discern whether presenting to others that which is holy will elicit nothing but abuse or profanity” (128).

Does anybody now wish to take back some internet comments he or she has made?

Conclusion

Bible study is all about incremental gains in understanding and skill. At least I hope it is. I hope I’m not finished getting insights into Scripture and refining my understanding of it. I have read the Sermon on the Mount many, many, many times—and I don’t think it ever occurred to me to explore this verse’s connection to Jesus’ preceding statements.

Until I saw the paragraphing in my CSB. Whether I’m right or wrong, some editor somewhere helped me ask a helpful interpretive question. Thank you, nameless editor. Thank you, paragraphing.

***

Get started with free Bible software

Compare translations, take notes and highlight, consult devotionals and commentaries, look up Greek and Hebrew words, and much more—all with the help of intuitive, interactive tools.