Friendship can overcome even the most intense disagreements.

Case in point: the Catholic apologist and satirist G.K. Chesterton found an unlikely friend in George Bernard Shaw, the modernist writer who famously balked at Christian mores.

The pair was a study in contrast, both physically and philosophically. On one occasion, Chesterton quipped to Shaw, “To look at you, anyone would think a famine had struck England.” Without missing a beat, Shaw returned, “To look at you, anyone would think you have caused it.”

Chesterton and Shaw often engaged in public debates (once on the tongue-in-cheek question of “Do we agree?”), but privately were close companions who held one another in great esteem.

But friendship can do more than bridge divides; sometimes, friendship changes minds.

The friendship that changed Protestant art

Lucas Cranach was one of the most sought-after artists in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Germany. He produced woodcuts, engravings, even currency—but he is best known for his paintings. Portraits were his favorite, and nobility and royalty often commissioned his work.

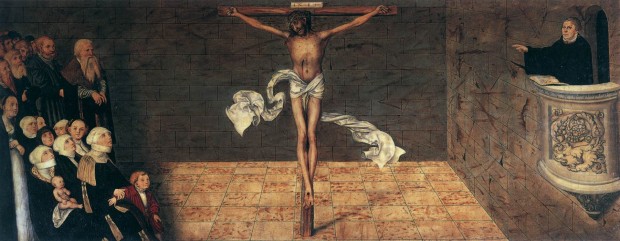

But Cranach shined brightest in his religious works. When he became a Protestant, his artwork shifted from its formerly Catholic preoccupations. Gone were the depictions of Madonnas, the Passion, martyrs, and saints; in their place stood distinctly Protestant portrayals on themes like sin, grace, and God’s Law. Much of that change reflected Cranach’s close friendship with Martin Luther. But that friendship didn’t just alter Cranach’s approach to art. Cranach was instrumental in Luther’s evolving viewpoint on the place of art in worship.

The balance of beauty and piety

In the wake of the Reformation, iconoclasm gripped much of Western Europe. This aversion to religious images—and especially their veneration—was a rejection of Catholic practice. Reformers decried crucifixes, ornate altar pieces, and religious icons, arguing they competed with God for his devotion. For more than 40 years, the most ardent iconoclasts ransacked churches and destroyed untold scores of artwork.

Initially, Luther shared many of the sentiments of the iconoclasts. But he later came to believe that beauty need not forestall piety. In fact, during his lifetime, he actually commissioned religious artwork—from none other than Cranach himself.