Ancient biblical scrolls discovered in Qumran

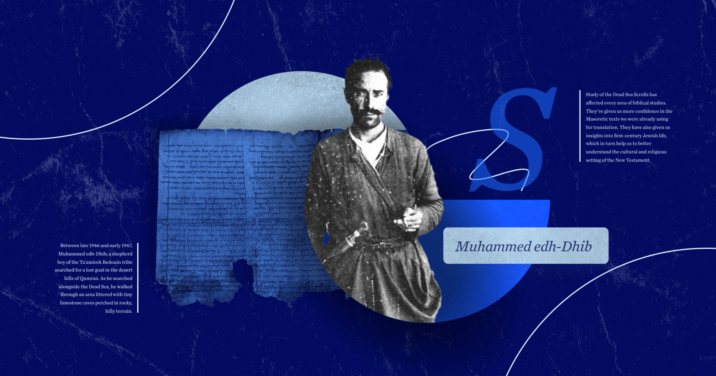

Between late 1946 and early 1947, Muhammed edh-Dhib, a shepherd boy of the Ta’amireh Bedouin tribe searched for a lost goat in the desert hills of Qumran. As he searched alongside the Dead Sea, he walked through an area littered with tiny limestone caves perched in rocky, hilly terrain.

Muhammed tossed a rock into a cave in which he suspected that one of his goats might have taken refuge. But instead of striking goat or rock, he struck pottery. The unmistakable tinkle of shattered clay reached his ears. In this cave, now called Cave 1, he discovered several clay jars containing seven ancient scrolls. Little did he know, he had made probably the most important Bible-archaeology find of the 20th century, or perhaps of any century. For in these caves lay ancient manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible dating back to before the time of Jesus.

A selling spree

Rather than alerting the authorities, Bedouin shepherds kept the location of the caves a secret—and went on a selling spree.

They sold four scrolls to a well-known antiquities dealer in Bethlehem named Kando, who then sold them to the archbishop of the Monastery of St. Mark’s in Jerusalem. They sold the other three scrolls to an antiquities dealer in Bethlehem named Feidi Salahi, who sold them to Eleazar Sukenik, a Hebrew University Professor in Jerusalem.

When the shepherds found more caves with more scrolls, they brought most of them to Kando.

Finding the caves

The locations of the Qumran caves remained a secret until British archaeologists searched the area sometime later. There they discovered more caves and more scrolls. In Cave 4, they found 15,000 fragments—parts of 600 manuscripts. These Hebrew scrolls had been buried rapidly in the cave floor rather than in jars—perhaps as their owners fled from danger.

In total, 11 caves were discovered, one of which (Cave 7) contained scroll fragments in Greek. Archaeologists also found a site in Qumran that seemed possibly to be linked to the scrolls. The site contained writing tables, inkwells, and pottery kilns. Scholars still speculate as to who the scribes were, where they came from, and why they were there. It’s commonly believed they were Essenes, an ancient Jewish sect.

Studying the scrolls

As scrolls were discovered, scholars began to study them—but only a select few scholars, a fact that will become significant later in our story.

Israel acquires the Dead Sea Scrolls

After the Arab-Israeli war started in 1948, four of the Dead Sea Scrolls were offered for sale through an ad in America’s Wall Street Journal. Archaeologist Yigael Yadin purchased them anonymously for the State of Israel for $250,000 (nearly $2.8 million in today’s money). These scrolls, along with three others, came to be displayed in the Shrine of the Book, a museum built in Jerusalem specifically to house the scrolls. Others were displayed in museums of other countries.

Certain scrolls and scroll fragments were displayed publicly, but the select researchers who had access to study them took their time. For 40 years, reliable information about the scrolls trickled out only rather slowly.

This was about to change.

The secret Dead Sea Scrolls concordance

The first group of researchers working on the scrolls in the mid-1950s saw the need for some tools to do their work, so they put together a sort of card catalog concordance. They listed every word in the Scrolls on 3 by 5 cards, along with a little bit of context and the name of the document from which each word came—not wholly unlike Strong’s famous concordance. All of this material was created and sorted by the late 1950s. The concordance was kept in the Scrollery at the Palestinian Archaeological Museum.

By the late 1980s, the catalog had been copied and disseminated more broadly so that the select Scroll scholars could work in places other than Jerusalem. Scholar Hartmut Stegemann headed up a project to take that card concordance, photocopy it, and publish a private version of it.

The concordance was published with about 21 cards on a page in four or five volumes, and it was sent to various locations around the world.

Marty Abegg

Enter evangelical scholar Martin Abegg. Abegg was a young student at the Hebrew University when Emanuel Tov taught his first class on the scrolls from 1986–1987. This introduced Marty to the topic of the Dead Sea Scrolls—and forever changed his career path.

But this did not mean that Abegg became part of the inner ring with access to the scrolls themselves—he didn’t even know about the concordance until several years later. Abegg says, “It was a secret. It was known only among the scholars that were officially working on the scrolls. But it’s difficult to keep that sort of thing secret for very long. People talk.”

Abegg furthered his studies at the Hebrew Union College and completed his degree under the teaching of Ben Zion Wacholder, and Wacholder had heard rumors of the secret DSS concordance. While on his way to a conference in Europe, Wacholder took a taxi with John Strugnell, the Editor in Chief of the scroll publication project for Oxford. Wacholder asked about the secret concordance. Strugnell, who held Wacholder in high regard, admitted that it existed.

Wacholder asked for a copy and received written permission from Strugnell to obtain one. Wacholder was virtually blind, however, so it was Abegg who wrote the letter asking for permission. Without knowing it, he had taken his first step toward the history books.

A copy of the concordance was duly located at a school in Baltimore, and the scholars there agreed to make a copy for Hebrew Union College. Abegg, who worked closely with Wacholder, gained access to this copy of the secret DSS concordance.

The secret is out

Abegg focused his research on what is known as the War Scroll, one of many DSS that was not from the Hebrew Bible. Abegg became aware that there were other manuscripts among the DSS that were related to the War Scroll, but he was denied access to them.

And then, suddenly, Abegg had an idea that would alter the history of the Scrolls—and open them to the world.

Abegg realized that with a little computer wizardry and a fair bit of diligence, he could reconstruct the text of the Dead Sea Scrolls from the concordance.

Abegg started by reconstructing the War Scroll, but he didn’t stop there. He also reconstructed other texts that he knew that his dissertation advisor would want to see. Wacholderhad waited 25 years for access to those texts, but he wasn’t part of the inner ring; he had been held at arm’s length.

And now a graduate student brings him a Dead Sea Scrolls concordance and plops it down on his desk. Within five minutes, Wacholder said, “We must publish.”

Abegg thought that if he published the concordance, he would be blackballed from the academic community. Abegg said, “You just don’t do this kind of stuff. This wasn’t my work. The reconstructions were mine, but the concordance was not. Scholars created the concordance. Most of them were still alive at that point. To publish this material was an academic no-no.”

Abegg consulted several people, and came to agree that scholars had waited for this information for 25 years. The DSS belonged to the world, and the current situation simply was not fair.

Publish and perish

Abegg convinced himself that they had to publish his reconstruction work. At first, it was difficult to find a publisher willing to take the risk. Brill wanted to publish the concordance but backed away due to their fear of legal action against them. They published Dead Sea Scrolls studies, and they didn’t want to risk any harm to that area of publishing.

But Wacholder came up with a solution. Abegg remembers Wacholder saying, “I know who would publish it; he’s been beating the drums and creating quite a stir. That’s Hershel Shanks of the Biblical Archaeology Review.” Shanks was immediately excited about the possibility and agreed to publish the reconstructions in 1991. Many scholars working on the scrolls were furious, but to Abegg’s relief, the work was welcomed both by scholars and by the public.

The official DSS editors at that time could have proclaimed the concordance as worthless for research. Instead, scholar Shemaryahu Talmon said that the reconstructions were so good she assumed Abegg and Wacholder had access to the photographs of the scrolls that were used by the official editors.

Unbeknownst to Abegg and Wacholder, Hebrew Union College was one depository of a truncated copy of original photographs of the DSS. It was natural, then, for Talmon to assume that they had access to these photographs and worked from them. This small but rational error in judgment—built on a chance fact—increased scholarly confidence in Abegg and Wacholder’s concordance. And the concordance in turn increased public interest in the Dead Sea Scrolls.

James VanderKam

At the Society of Biblical Literature meeting in November of that year (1991), James VanderKam read a paper that opened the doors for everyone with the proper skill and interest to begin researching the Dead Sea Scrolls. In just a few months, the situation had been turned completely on its head. Scholars outside of those working on the scrolls finally had a tool to work with. They could see things that were in other scholars’ hands that hadn’t yet been published officially.

Probably the most important result of Abegg’s fateful discovery—and decision—was blossoming interest among biblical scholars in the Dead Sea Scrolls. Abegg said, “For the next 20 years, it was like somebody had turned on the spigot and forgot to turn it off—in the money that was available, in the available research positions, and in the publications that were possible. I’m now the editor of the official concordance, which is an interesting irony. I blew the thing open with the first secret concordance and then was given the task by Emanuel Tov of producing the official concordance for the Oxford publication!”

Study of the Dead Sea Scrolls has affected every area of biblical studies. They’ve given us more confidence in the Masoretic texts we were already using for translation. They have also given us insights into first-century Jewish life, which in turn help us to better understand the cultural and religious setting of the New Testament.

Marty Abegg’s actions sped up the release of the scrolls and awakened public interest in them. Read on in this issue for insights into Scripture generated by the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

***

This article was originally published in the January/February 2022 issue of Bible Study Magazine. Slight adjustments, such as title and subheadings, may be the addition of an editor.

Related articles

- The Dead Sea Scrolls: 9 Common Questions, Answered

- What the Dead Sea Scrolls Reveal about the Bible’s Reliability

- 3 Ways the Dead Sea Scrolls Revolutionized NT Studies

Related resources

Freeing the Dead Sea Scrolls: And Other Adventures of an Archaeology Outsider

Regular price: $18.99