If you came to this site because you couldn’t resist seeing for yourself what Word by Word could possibly have to do with autopsies—gotcha! You will find no cadavers or gory CSI scenes here. All this goes to show that appearances can be deceiving, and you have to check things out for yourself. In fact, “autopsy” here just means exactly that: seeing something with your own eyes. It’s a fancy term traditionally used by manuscript scholars, many of whose knowledge of ancient languages and etymology far surpasses their everyday people skills or ability to communicate with others who don’t share their interests and training. In this usage, it refers to the act of looking at an original manuscript in person, rather than in images or transcriptions.

Why conduct an autopsy?

The obvious answer (to which no self-respecting scholar would admit) is, “Because it’s fun!” As hard as postmodernist philosophers may try, it’s impossible to drive away that primal urge to see the real thing—the original. When scholars invest time to study particular manuscripts and use them in their research, it can be a deeply satisfying and enjoyable experience to see these manuscripts in person. They have traced the evidence as far back as it goes to the original source itself and connected in a personal way with a special artifact that is, at the same time, foreign and yet familiar.

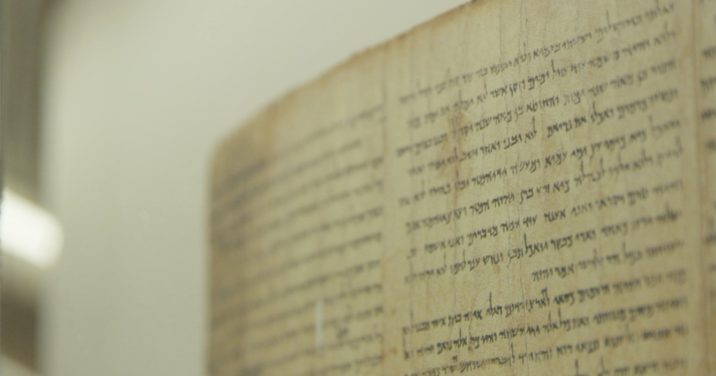

Whenever I take guests to see manuscripts, they inevitably take pictures of themselves with the manuscripts. And why not? Even scholars who look at manuscripts only for general interest usually come out with a smile on their faces. And countless hordes of interested laypeople regularly flock to see exhibitions like the Dead Sea Scrolls, even though most of them can’t read them or explain their significance. Looking at original manuscripts is simply a fun and meaningful way to connect to the past. You could call it a nice perk that comes with being a manuscript scholar.

On a more intellectual level, looking at ancient and medieval manuscripts is an excellent way to familiarize yourself with the different book cultures that gave us the Bible and other important texts. These cultures often differed from us in significant ways, such as the forms of the book, the materials used to craft it, the readers’ experience, and other details that are difficult to appreciate unless you have looked at the manuscripts in person. It reinforces that manuscripts are not just texts, but material artifacts.

The physical realia are also important for gaining an appreciation of the size of manuscripts, since it is easy to lose a sense of scale and perspective when zooming in and out of digital photographs. Even after many years of study, I am still often surprised about how small manuscripts look in person compared to what seems to be the case on a computer screen. Reading a cramped Greek minuscule in a poorly lit reading room is very different from zooming in on an online photograph on a computer. When I travel for work or on vacation, I often make a point to visit local libraries and museums to examine manuscripts of interest. Even if I never end up publishing on a particular manuscript, the frequent exposure makes me a better manuscript scholar.

But of course, for scholars, the most important reason to examine manuscripts in person is for the added value it can bring to research. In some cases, manuscripts are not published or are only available in relatively poor or difficult-to-access reproductions. In other cases, consulting the original can help confirm or correct previous work and resolve difficult issues that are not obvious from available photographs. For manuscripts that have been photographed with cutting-edge techniques (e.g., high resolution, various wavelengths of light and lighting source direction), my experience is that consulting the originals only rarely adds new information for reading the two-dimensional surface of written documents. Where “autopsy” is crucial is in studying manuscripts as three-dimensional textual artifacts, with thickness, texture, and damage that are not readily visible in most types of photographs. To give one interesting example, towards the end of a famous Psalm scroll from Qumran (11QPsa), there is a prose epilogue that begins with the first three lines indented (see the second column from the left here). Some scholars have suggested that the scribe intentionally did this to highlight that this section was a different genre of text than the Psalms around it. But when you look at the scroll in person, you can clearly see a rough patch at exactly that point. There was a defect in the parchment preparation process, and the scribe was simply avoiding the defective surface as he does at many other places in this scroll. Thus, despite the very high quality of images that are currently available for many artifacts, examining manuscripts in person remains essential for expert analysis of manuscripts.

Gaining access

The custodians of ancient and medieval manuscripts (especially curators and conservators) have a very important and challenging job of preserving some of our cultures’ most valuable artifacts, while at the same time making them available to the world to see, study, and appreciate. Every time a manuscript is displayed, touched, moved, exposed to light or different temperatures, etc., there is damage that, however minor, accrues over time and threatens its preservation. Conservators are skilled professionals who take very seriously their responsibility to reduce this risk and safeguard the manuscripts for future generations. And for this reason, it is very important that you follow their instructions carefully, e.g., to touch or not, gloves or no gloves, time and type of light exposure, etc.

And yet, books were made to be read. I once gave a Gideon’s New Testament with Psalms to a friend in the Marine Corps who was deploying to Iraq. When he returned, he proudly informed me without a hint of irony, “It never left my pocket!” In the same way, it would be a shame for a good book to remain locked in a vault permanently, even if it lasted a thousand years or longer. Thus, most institutions also take seriously their responsibility to make their materials accessible to the public, especially to scholars with legitimate research needs.

The policies for accessing manuscripts can vary greatly from institution to institution, and usually you can find contact information on their websites. It is important to identify in advance which manuscripts you want to examine and to plan ahead, since there are often unforeseen logistical challenges. Many institutions require some form of credentials or a letter of recommendation from a credentialed supervisor to demonstrate the legitimacy of the researcher.

Depending on the institution and the value and condition of the manuscripts, you may also need to explain why consulting the manuscript is necessary for your research. Perhaps your manuscript of interest is not published or easily accessible. Or perhaps you need to look at something specific that is not obvious on available photographs. Of course, there are no guarantees. The Cambridge University Library once kindly allowed me to flip through volumes of biblical fragments from the Cairo Genizah, but when I asked if it was possible to see Codex Bezae, I received a flat, “No!” But, hey, it can’t hurt to ask! You might be pleasantly surprised at how easy it is for legitimately interested people to get access to fascinating manuscripts, even if you’re not an expert manuscript scholar yourself.

If you don’t have the research skills or interests to convince a particular archive to open up its vault, it is still possible to examine ancient and medieval manuscripts in person. Many libraries and museums exhibit selections of their holdings for the viewing public, which can provide a wonderful exposure to original manuscripts along with some guidance about their significance for the uninitiated. This is a great place to start familiarizing yourself with manuscripts, and you may even be able to see famous manuscripts that would make professional textual scholars jealous. If you are ever in London, stop by the British Library. You will be amazed at what you can see. Even if you can’t get access to specific Dead Sea Scrolls in the Israel Antiquities Authority lab, some of the best preserved and most famous scrolls are open to the public in the Shrine of the Book in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. And there are countless other exhibitions throughout the world for your viewing pleasure and hands-on (well, maybe not literally) learning.

What to bring

If you are able to arrange a viewing, what should you bring with you? Of course, this depends on your research needs and what the institution has available in its reading room. But it is usually a good idea to bring an old-fashioned magnifying glass and perhaps a small light source. I always bring a ruler and protractor with me. A digital camera (and for more serious research, a digital microscope) may also come in handy if the curators will allow it. And, of course, don’t forget a computer (fully charged!) and/or note paper (often only a pencil is allowed in the reading room) to record your observations from the visit. If you research what you are going to see before your visit and even prepare a list of specific research questions, you will find that makes the experience even more profitable.

Conclusion

Despite the unappealing medical associations of the word, “autopsy” can be a pleasant learning experience, both for the expert and the layperson alike. So the next time you are at a library or museum, try to see if it is possible to look at some of their manuscripts in person. It may forever change the way you see books and the textual history of the Bible and other works that have been passed on through the ages. But one final word of warning: once you start, you may find it impossible to stop!