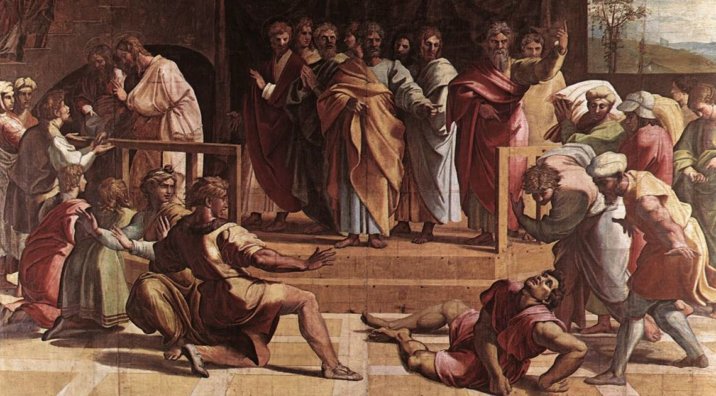

1. Ananias and Sapphira are a foil

In all the shock and awe of the couple’s fate, it’s easy to forget the first word in the story: “But.” (The chapter division certainly doesn’t help, either.) Ananias and Sapphira’s deceit and greed stand in contrast to the sincerity and generosity of the community of faith (4:32–37). Read 5:1–11 and then go back and read the paragraph before, and a sense of sadness may come upon you. There is euphoria and utopia in the scene described. “One heart and soul,” “everything in common,” “not a needy person among them.” “But a man named Ananias . . .” A dark cloud invades the scene. Greed and deceit enter the community like a virus. Amid the glorious expansion of the church, Ananias and Sapphira sneak in as a threat. Note, too, that Sapphira falls down dead at Peter’s feet (5:10), whereas Joseph brought all his money and laid it at the apostles’ feet (4:37). The generous disciple held God’s authority in high esteem and showed it by laying his possessions at his appointed messenger’s feet. Ananias and Sapphira did not, and God made his authority known by laying them down.2. There are strong parallels to Joshua 7

Commentators are quick to point out parallels, whether intended by Luke or not, to the story of Achan in Joshua 7. F.F. Bruce writes in the Acts commentary in the NICNT series:The story of Ananias is to the book of Acts what the story of Achan is to the book of Joshua. In both narratives, an act of deceit interrupts the victorious progress of the people of God. It may be that the author of Acts himself wished to point this comparison: when he says that Ananias “kept back” part of the price (v. 2), he uses the same Greek word as is used in the Greek version of Josh. 7:1 where it is said that the Israelites (represented by Achan) “broke faith” by retaining for private use property that had been devoted to God.1 In the very least, this parallel reminds us it is not out of character for God to bring swift judgment and guard his holiness. But the parallels go beyond verb choice:

- Both events happen amid new beginnings: Israel just coming into the promised land and the New Testament Church taking root in Jerusalem. Could it be God is zealously guarding his tender shoot?

- Both events concern greed and possession. God had commanded the Israelites not take any devoted things into the camp (Jos. 6:8), and the budding church had made it a practice to sell all that they had.

- God swiftly and corporately punishes both parties. A notable difference is that Achan’s whole family is punished with him, whereas Ananias and Sapphira are punished individually.

3. Satan was trying to thwart the Spirit

Ultimately, this passage is not about Ananias and Sapphira lying to the assembly and keeping back a portion for themselves. It’s about them lying to God (5:3, 9). Peter himself indicates that the two could have just as well kept back a portion for themselves; it was theirs to do with as they pleased (v. 4). Instead, they presented it as all they had (in context, the phrase “laid it at the apostles’ feet” in verse 2 makes this clear). You see in Peter’s somewhat prophetic statement in verse 3, “Ananias, why has Satan filled your heart to lie to the Holy Spirit”?” that principalities are at war. Satan is trying to get a foothold because he sees how powerfully the Spirit is moving. Whereas the community was “filled” with the Holy Spirit (4:30), Ananias was “filled” with Satan; “he has become Satan’s plaything.”2 As John Stott put it, “If the devil’s first tactic was to destroy the Church by force from without, his second was to destroy it by falsehood from within.”3 And so this is not simply a story of greed in the early Church. It’s about an attack on the church from within—an enemy scared and trying to stop the great momentum of the gospel.4. The story is not normative

There is nothing in this story, Acts, or the New Testament as a whole that indicates this is a pattern for how God acts. In fact, if it were, the pattern would break in Acts 8 with Simon the sorcerer. Though Ananias and Simon’s acts and motivations are slightly different, Peter’s rebuke has a similar solemnity to it—and death is even warned. However, Simon responds with a repentant heart and is seemingly spared. It is better to take this as a unique moment of sudden divine judgment. The people’s great fear indicates this was not something they were accustomed to, either.5. The assembly’s response matters most

As is often the case with difficult texts, there is a temptation to read more than is there. But a rule of responsible Bible reading is to pay the most attention to what the author draws the most attention to. Luke’s repeated “Great fear came upon all who heard it / the whole church” (v. 5, 11) is the focal point. In fact, this is not the only time awe is inspired in Acts (2:43; 9:31; 19:17), which reinforces this reading. The phrase “and the word continued to spread” functions this way in Acts, too (6:7; 12:24; 19:20; 13:49). Throughout Luke and Acts, Luke often ends stories with such summative statements (see Luke 1:12, 65; 2:9; 5:26; 7:16; 8:25, 35, 37; 9:34, 45; 21:26). So what are we to do with our questions about this passage? I appreciate what Bruce says:It is no part of a commentator’s work to pass moral judgment on Peter; it would be necessary, in any case, to know much more than is stated in the narrative. Sapphira, for aught that is known to the contrary, may have suggested the deceit to her husband. [I disagree with Bruce—verse 1 suggests Ananias took the initiative.] It is not Peter’s character or even Ananias and Sapphira’s deserts in which Luke is primarily interested. What he is concerned to emphasize is the reality of the Holy Spirit’s indwelling presence in the Church, together with the solemn practical implications of that fact.4 Our takeaways from the text should probably be no more and no less than that of the people who witnessed the event: fear and awe. God is a holy God who vanquishes evil and zealously defends his holiness. His judgments are his, and he only makes some of them known. Why did God strike down Ananias and Sapphira rather than give them a chance to repent? How is it that Satan filled Ananias’ heart to lie (v. 3) but that Ananias also contrived the sin himself (v. 4)? Why didn’t Peter show the same grace toward Ananias and Sapphira that he was shown for his deceit and denial of the Lord (Matt 26:69-75)? We do not know. The text does not speak to these questions, though other passages may help us find answers. Ultimately, though, it’s the text that demands an answer from you: Do you fear God?

Related articles

- The Unforgiveable Sin: Evidence You Have Not Committed It

- Does God Always Give Second Chances? John Says “No.”

- Strange Fire in Leviticus 10, and Why It Earned a Death Sentence

- Bruce, F.F. The Book of Acts in the New International Commentary on the New Testament (Eerdmans, 1988), pg. 102.

- Joseph Fitzmyer, The Acts of the Apostles in the Anchor Yale Bible series (Yale University, 1974), pg. 323.

- Quoted by David Peterson, The Acts of the Apostles in the Pillar New Testament Commentary (Zondervan, 2009), pg 210.

- Bruce, 104.