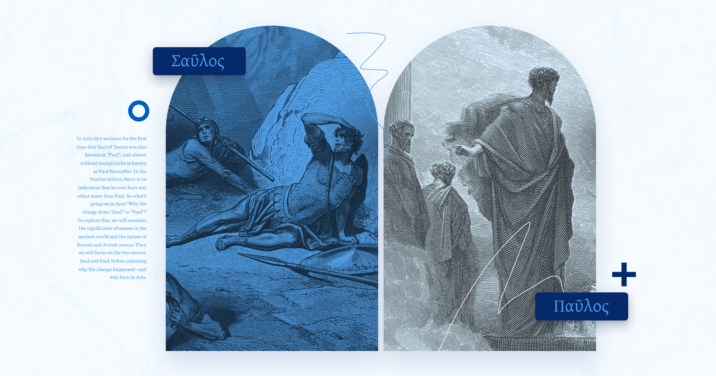

In Acts 13:9 we learn for the first time that Saul of Tarsus was also known as “Paul”; and almost without exception he is known as Paul thereafter. In the Pauline letters, there is no indication that he ever bore any other name than Paul. So what’s going on in Acts? Why the change from “Saul” to “Paul”?

To explore this, we will consider the significance of names in the ancient world and the nature of Roman and Jewish names. Then we will focus on the two names, Saul and Paul, before assessing why the change happened—and why here in Acts.

The significance of names

Names were significant in the ancient world, as in much of the world today. A person’s name said something about them, maybe a characteristic of the person, or who a significant ancestor was. Changes of name were particularly significant, such as Abram (“exalted father”) becoming Abraham (“father of many”) because of God’s promise to him of many descendants (Gen 17:5). Or think of Jacob (“heel-grasper,” Gen 25:6) becoming Israel (“he who fights with God,” Gen 32:28 [MT 32:29]; 35:10) after Jacob spends the night wrestling with the mysterious figure who dislocates his hip, and the figure assures him he has prevailed with both people and God.

Double names were widespread in the Greco-Roman world from the second century BC to the third century AD, in both Greek and Latin—as well as in Nabataean, Hebrew, Palmyrene, and Egyptian.1 Other than Saul/Paul, New Testament examples include Cephas/Peter (John 1:42), John/Mark (Acts 12:12, 25; 15:37), Tabitha/Dorcas (Acts 9:36), Jesus/Justus (Col 4:11), and Simeon/Niger (Acts 13:1). Indeed, double names are still used today, such as the Brazilian soccer player Pelé, whose birth name was Edson Arantes do Nascimento.

The nature of Roman names

In the first century AD, Roman citizens had three names, written in the order praenomen, nomen, and cognomen.2 The nomen was the family name, received at birth or on gaining citizenship. The praenomen was taken from a limited list (only eighteen by the time of the late Roman republic), and frequently abbreviated to one letter: e.g., M. = Marcus; G. = Gaius. The praenomen, then, distinguished family members who shared the same nomen. The cognomen was the name by which people were commonly known, and was sometimes derived from that of a relative. Slaves who became citizens generally kept their previous (single) name and acquired a nomen and praenomen. Frequently they took their liberator’s nomen, particularly if freed by their master or mistress; sometimes they took the name of the emperor at the time of their liberation. It is highly likely that Paulus was Saul’s cognomen. We do not know his nomen or praenomen.

Jewish people who were Roman citizens, as well as those from other non-Italian ethnic groups, frequently had a fourth name, the signum or supernomen. Within their ethnic community, they would be known by that name. It is probable that “Saul” was a Jewish supernomen.3

The names used

Σαῦλος/Σαούλ (Saulos/Saoul), “Saul” in Hebrew (שׁאול šʾwl, meaning “[the child] asked for”), was his Jewish name, and he would be known thus among Jews—at least prior to his Damascus road encounter with Jesus. This name was relatively widely used in Palestine, but rare among diaspora Jews such as this Saul.4 The two Greek spellings reflect (respectively) Greek-speaking and Hebrew/Aramaic-speaking settings: Σαούλ is a transliteration into Greek of the Hebrew form. In Acts prior to Cyprus—that is, predominantly in Jewish or mixed Jewish and Gentile settings—he is “Saul” (Σαῦλος; Acts 7:58; 8:1, 3; 9:1, 8, 11, 22, 24; 11:25, 30; 12:25; 13:1, 2, 7). The Hebrew form Σαούλ occurs only in the context of the Damascus road story in Acts (9:4, 17; 22:7, 13; 26:14)—and neither “Saul” form is used in Paul’s letters.

Saul was from the tribe of Benjamin (Phil 3:5). He thus shared his name with the most famous member of his tribe, King Saul (Acts 13:21; 1 Sam 9:1–2; LXX consistently uses the spelling Σαούλ), prompting Kochenash’s intriguing suggestion that the Christian Saul is being contrasted with his royal predecessor:

Just as King Saul persecuted David, so Saul of Tarsus persecutes the Son of David.5

In Cyprus, Saul/Paul rejects magic practiced by Bar-Jesus/Elymas, whereas King Saul practices magic and is killed by YHWH for this (1 Sam 28:7; 1 Chr 10:13 LXX). Thus some suggest that Saul’s shift of name to “Paul” was an effort to dissociate himself from King Saul’s sin. At best, this is an interesting (modern) readerly response.

The Greek form of the name, Σαῦλος, could be problematic among Greek-speakers, since the adjective σαῦλος conveyed “effeminate” or “conceited,” and the cognate verbs σαυλοπρωκτιάω and σαυλοόμαι could mean walking in an effeminate manner. This association might (at least in part) explain a preference for “Paul” in Greek settings.6

The Latin name Paul(l)us went into Greek as Παῦλος (Paulos), although the inscriptions and literary sources do not contain many examples of Romans bearing this name. Other than Saul/Paul, we have few examples of Jewish people with this name in the Greek East in the first century—Bauckham cites only two examples.7

Paul(l)us means “small” (like the modern “shorty”), which might indicate that he was little when born. Bauckham (among others) wonders if assonance between Saulos and Paulos might explain how a Jewish child called “Saul” received the Latin name “Paul”; the most we can say is that is possible.8

Paul informs the tribune in Jerusalem that he was born a citizen (Acts 22:28), but we know nothing about how Paul’s family received Roman citizenship. Various suggestions have been made: that a famous Roman of a previous generation gave citizenship to prominent residents of Tarsus, including one of Paul’s ancestors (perhaps his father); that Paul’s forebears were freed from slavery by a Roman and in the process made citizens; or that Paul was the name of Paul’s forebears’ Roman patron.9

Acts 13:9 is a watershed in terms of the naming of Saul/Paul. After Cyprus, the only uses of “Saul” (in either spelling) are in the retellings of the Damascus road experience, and they are always the double Σαοὺλ Σαούλ, transliterating the Hebrew form. Saul reports that the voice spoke “in the Hebrew language” (Acts 26:14), which makes good contextual sense. Before Cyprus, the name “Paul” is never used, and after Cyprus it predominates heavily, except for accounts of the Damascus road experience.

The wording of the hinge passage, Acts 13:9, repays attention. Σαῦλος … ὁ καὶ Παῦλος means “Saul … also known as Paul”—this is a standard expression used when a person is known by two names.10 The wording thus indicates that Paul is not receiving a new name, but that a name that he already has is being used—so most probably the Latin Paulus was his cognomen.11

Why the change?

Four main reasons have been proposed for the name change at this point in Acts. They are a mixture of historical and literary explanations—that is, explanations focused on what happened on the ground in the first century or on how Luke presents his story of Paul.

The hinge in Cyprus prompts some—going back to Jerome (Vir. ill. 5)—to propose that the change of name was historical and resulted from Saul’s encounter with Sergius Paulus, the Roman governor of Cyprus (Acts 13:7). He may well be Lucius Sergius Paulus, known from an inscription marking the bank of the river Tiber in Rome.12 Classicist Stephen Mitchell proposes that Sergius Paulus adopted Paul as a client,13 and this led to the change of name, but this view stumbles on the probability that Saul had both names from childhood.

Ramsay more plausibly suggests that Luke’s usage reflects the role Saul/Paul is playing in the narrative.14 He combines this with arguing that, historically, Paul’s policy of being “all things to all people, that I might by all means save some” (1 Cor 9:22) accounts for such a change. Rather than introducing himself as a Jew from Tarsus, as Paul does in relation to Jewish audiences elsewhere (Acts 22:3; cf. 21:39), it would be natural in the court of the Roman governor to use his Roman cognomen. On this view, once Paul’s engagement with gentile mission began in earnest, from Cyprus onwards, it would be most natural, historically and literarily, for him to use “Paul.”

Barrett’s approach is not dissimilar, although rather than look forwards from Cyprus to the rest of Acts, Barrett looks back to the earlier part, where “Saul” is used without exception.15 He thus proposes that the point of using “Saul” before Cyprus is to establish that this believer in Jesus is profoundly Jewish, for he is known by his Jewish name. This certainly chimes with some work on Acts which highlights the Jewish flavor of much of Luke’s writing.16

Finally, the audience in the text is worthy of attention, in light of Ramsay’s insight above based on 1 Corinthians 9:19–23. Ananias, Saul’s first believing Jewish contact after the Damascus road experience, addresses him as Σαοὺλ ἀδελφέ, “brother Saul” (9:17; 22:13), probably in Aramaic. The heavenly voice speaks to him using Σαοὺλ Σαούλ, “Saul, Saul” (9:4; 22:7; 26:14), and in the third account of the Damascus road experience Paul discloses that this was “in the Hebrew language” (26:14). Taking into account both the audience and whether the story takes place pre- or post-Cyprus appears to offer a comprehensive picture. In Jerusalem, he is known as “Paul,” and this is in Luke’s narrator’s voice, and Paul is in process of being taken into Roman custody (Acts 21:32, 37, 39, 40). In Luke’s voice, rather than characters’ voices, after Cyprus, it is consistently “Paul,” even in Jewish settings (e.g. 17:2–4; 18:5; 28:25).

Related articles

- Should I Read the Bible Like Any Other Book?

- How to Use Linguistics to Understand the Bible

- 7 Things about the Bible I Wish all Christians Knew

- G. H. R. Horsley, “Names, Double,” in Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, ed. David N. Freedman (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 4:1011; G. H. R. Horsley, ed., New Documents Illustrating Early Christianity (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1981), 1:89–96.

- More fully, see Heikki Solin, Oxford Classical Dictionary, s.v. “Names, personal, Roman.”

- Joseph B. Fitzmyer, The Acts of the Apostles, Anchor Bible 31 (New York: Doubleday, 1998), 502.

- Richard Bauckham, The Jewish World around the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2010), 375, 377–78.

- Michael Kochenash, “Better Call Paul ‘Saul’: Literary Models and a Lukan Innovation,” Journal of Biblical Literature 138 (2019): 433–49, quoting 439.

- T. J. Leary, “Paul’s Improper Name,” New Testament Studies 38 (1992): 467–69, here 468; Robert Beekes and Lucien van Beek, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, s.v. “Paul”; Henry G. Liddell, Robert Scott, Henry S. Jones, and Roderick McKenzie, eds., A Greek-English Lexicon, s.v. “Paul.”

- Bauckham, Jewish World, 375.

- Bauckham, Jewish World, 377–78.

- Respectively suggested by William M. Ramsay, The Cities of St Paul: Their Influence on His Life and Thought: The Cities of Eastern Asia Minor (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1907), 205–14; Martin Hengel and Roland Deines, The Pre-Christian Paul (London: SCM, 1991), 11–14; Rainer Riesner, Paul’s Early Period: Chronology, Mission Strategy, Theology (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1998), 146.

- Horsley, New Documents, 1:89–90; Horsley, “Names, Double,” 4:1012 §B.1.

- G. A. Deissmann, Bible Studies (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1901), 313–14; Stephen B. Chapman, “Saul/Paul: Onomastics, Typology, and Christian Scripture,” in The Word Leaps the Gap: Essays on Scripture and Theology in Honor of Richard B. Hays, eds. J. Ross Wagner, C. Kavin Rowe, and A. Katherine Grieb (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2008), 214–43, here 225.

- Text, translation and discussion: Alanna Nobbs, “Cyprus,” The Book of Acts in its Graeco-Roman Setting, eds. David W. J. Gill and Conrad H. Gempf, Book of Acts in Its First Century Setting 2 (Carlisle: Paternoster; Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1994), 279–89, here 284–87; Markus Öhler, Barnabas: die historische Person und ihre Rezeption in der Apostelgeschichte, Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum neuen Testament 156 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2003), 282–85.

- Stephen Mitchell, Anatolia: Land, Men, and Gods in Asia Minor, 2 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon, 1995), 2:7.

- William M. Ramsay, St. Paul the Traveller and Roman Citizen (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1895), 81–83.

- C. K. Barrett, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Acts of the Apostles, 2 vols (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1994, 1998), 1:609, 616.

- See, e.g., Jacob Jervell, The Unknown Paul (Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1984); Jason F. Moraff, “Recent Trends in the Study of Jews and Judaism in Luke-Acts,” Currents in Biblical Research 19 (2020): 64–87; David Andrew Smith, “The Jewishness of Luke-Acts: Locating Lukan Christianity amidst the Parting of the Ways,”Journal of Theological Studies new series 72 (2021): 738–68; Isaac W. Oliver, Luke’s Jewish Eschatology: The National Restoration of Israel in Luke-Acts (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021).