Is it dangerous to accept changes to our language? Does doing so amount to moral relativism?

I once had to stand as a young man in front of an adult Sunday school class and wait for ten minutes (it felt that long, anyway) while a much older man in my class rebuked me for teaching that change is a God-given feature of language. He was a good man, a godly one, even an educated one. But he was certain that I was on a slippery slope. Was he right?

The idea that language change is morally bad is mostly a hidden assumption. And I get its intuitive appeal: we know language is a communal thing. It feels wrong for someone to change it without our consent. It’s like changing the code on the back door. It’s a violation of family trust. It locks us out.

As Ammon Shea wrote in his book Bad English: A History of Linguistic Aggravation,

There are two things that have remained constant: The English language continues to change and a large number of people wish that it would not.

Let me explain briefly why language change is actually a good thing for Christians who love God and his word.

First, knowing that language changes brings minor benefits to your sanctification. It will help you not be rude, for example, when you hear other people languaging wrong. Correcting kids or students is one thing; telling a fellow competent adult not to say “go lay down” is just unkind. Maybe at one time, the lie–lay distinction was widely observed, but it was never heaven-sent truth, and it’s OK that most people “violate” it all the time.

Second and more seriously, knowing that language changes drives Christians back to the Bible. And in two ways:

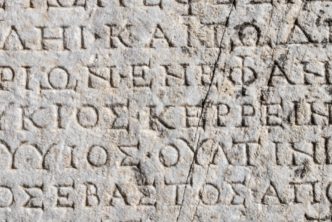

(a) The phenomenon of language change drives people back to translation of the Bible. On this topic I never tire of quoting C. S. Lewis, who said that you cannot buy your son a suit “once and for all”—he will grow out of it. Likewise, Lewis said, you can’t translate the Bible once and for all, “for language is a changing thing.” Language change is one of the forces that sends many Christians in every generation back to the Hebrew and Greek sources, continually refreshing the stream of Christian understanding of Scripture.

(b) The phenomenon of language change also drives people back to teaching the Bible. Language change means, as my editor said to me recently, that “we must never stop reading and expositing the Scriptures.” Spurgeon didn’t preach the Bible “once and for all”—nor did Calvin, Luther, Augustine, or Chrysostom. Changes in language (and in culture) send teachers and preachers back over and over to that same fresh stream of divine words.

The Old Testament people of God both were and were not a missionary people. They were supposed to be a “kingdom of priests,” even a “holy nation” displaying God’s character to the world. Jewish prophets frequently wrote woes to the nations, but they didn’t tend to go to them. The most famous prophet who did go, Jonah, was perhaps not the best representative of the God who sent him. And yet ancient Jews did find the energy to translate their sacred Scriptures into at least one other language, namely Greek.

Christians have a much clearer commission to take truth outward to the nations. It’s imperative that we honor and even marvel at—gotta quote my editor again—“the gospel’s awesome capacity for translation.” God can speak every language and every historical version of every language. God’s words can go anywhere, and they can go “anytime.” (See how flexible language is? I just invented a new sense for a common word!)

There are changes to English that I reject. Tip: if it takes the Twitter Police to enforce a given change, it’s not a real change; it’s politics. But Christians who insist that language shouldn’t change must do so using words that are themselves the results of language change. I encourage Bible students: learn to see the benefits of language change!

***

This article was originally published in Bible Study Magazine.