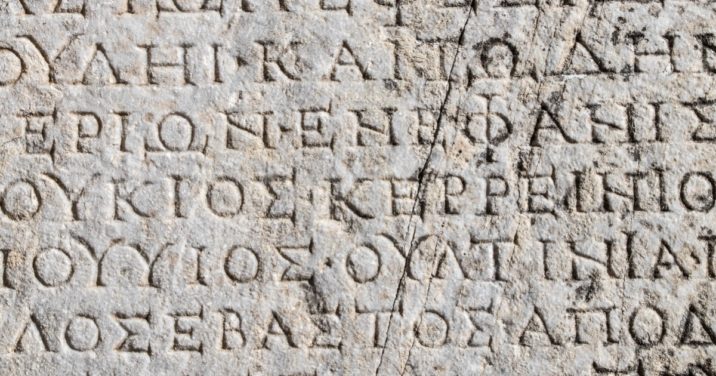

This is the second article in a two-part series dealing with the common myth that Greek is the most precise language known to mankind.

I’d like to look at a few more examples of imprecision in the Greek of the New Testament before offering some thoughts on how to deal with the ambiguities God inspired there.

The exciting world of circumstantial participles

We need to start by talking about something most people are blessed to give little attention to: circumstantial (adverbial) participles in Koine Greek. (Have patience: this will pay off!) The label indicates what these verb forms do: they describe the circumstances in which the action of the main verb takes place. For reference, circumstantial participles are like the English participle—verbs ending in -ing—in a sentence like this: “While running, he fell.” Such participles are very common in Greek, and they play a much more important role in that language than they do in English. They are also an inherently imprecise way of conveying the ideas which they communicate.

Consider what the venerable A. T. Robertson—the most influential New Testament Greek grammarian writing in English in the 20th century—said about circumstantial participles:

In itself, it must be distinctly noted, the participle does not express time, manner, cause, purpose, condition or concession. These ideas are not in the participle, but are merely suggested by the context. … There is no necessity for one to use the circumstantial participle. If he wishes a more precise note of time, cause, condition, purpose, etc., the various subordinate clauses (and the infinitive) are at his command.”

Robertson, the great Baptist grammarian, says that circumstantial participles are inherently imprecise.

Robertson, the great Baptist grammarian, says that circumstantial participles are inherently imprecise.

Matthew 28:19 affords one famous example of this imprecision. Consider the difference in the way the following two translations of the beginning of the Great Commission run:

- “Therefore, as you go, disciple people in all nations.” (ISV)

- “Therefore go and make disciples of all nations.” (NIV)

In Greek, the word translated “go” is one of these circumstantial participles. Painfully literally, it’s, “Going, make disciples.” The main verb in verse 19 is the command, “disciple” (ISV) or “make disciples” (NIV). According to the ISV, the command here is to make disciples “while going about (normal) life.” According to the NIV, the command is to “go and make disciples.”

For reasons beyond the scope of this article, most translations go with the NIV’s option here. They translate the Greek participle “going” as a command: “Go!” But that doesn’t mean the ISV is wrong: the Greek circumstantial participle makes its reading equally possible. The (never-ending) debate is over which meaning is more probable, given the context. In a definite sense, God gave us this debate. The text is not spiritually deficient for having a degree of ambiguity. Jesus spoke with purposeful imprecision, and he used a common imprecision in Greek grammar to do it.

Far more could be said about Greek participles—or many other facets of Greek grammar—but this example eloquently sums up the difficulty in treating them: Greek participles are a choice by the writer/speaker to be less precise rather than more precise.

Greek participles are a choice by the writer/speaker to be less precise rather than more precise.

Two practical tools for dealing with inspired ambiguities

The Greek nerd in me would love to continue piling up examples showing ways in which Greek can be imprecise. But it is fair to ask the question, “If scholars of New Testament Greek can’t always figure these things out clearly, what hope do the rest of us have?” Indeed, what are some practical ways of dealing with difficulties raised by imprecisions in Greek? Along with a healthy degree of humility in the entire process, here are two practical tools and two big-picture suggestions.

1. Translation comparison

First, you will likely only become aware of issues caused by Greek imprecision when many different English translations are in play. Translations often say roughly the same thing in slightly different ways, but sometimes they say different things—even if those differences are still themselves usually minor or subtle. Comparing multiple translations serves both to alert readers to possible difficulties in the text as well as sketch the general outline of possible solutions. When you notice a possible ambiguity by checking a different Bible translation, lean in: take a look at a few more to get the lay of the land, the range of translation possibilities.

2. Consulting commentaries

And then take the logical next step: go to the commentaries. For those with the resources (and Logos is built for this very thing!), a quick click to a commentary can be a valuable help in coming to grips with difficulties caused by imprecision in Greek. Commentaries rarely solve difficulties and ambiguities: they’re in the translations for good reasons. But commentators can at least serve as a wise guide on how to weigh the options.

The big picture

It’s ok if you find that some grammatical discussions in commentaries are too difficult to follow. Issues of imprecision in Greek usually end up in the domain of specialists. Indeed, truly understanding the options typically requires substantial knowledge of Greek. But there are some key mindset changes which are available to guard against the “Greek is super-precise” myth at a non-technical level.

1. Recognize that not all New Testament interpretive issues are due to English translation.

Bible translation is helpful and necessary—and necessarily imperfect. Many Bible readers are aware of this. In this and the previous article, I hope to have introduced an important category: sometimes the difficulty stems not from any inadequacies (real or imagined) in English, but to an inspired imprecision in the original Greek.

2. Hold a doctrine of Scripture which is not based on simplifications.

I suspect that the reason the “Greek is super-precise” myth hangs around is that in some quarters it is embraced as part of the doctrine of Scripture. Shoving the difficulties of understanding the text from the original to the shortcomings of translations can function as a safeguard of the adequacy of the inspired text. But this is to confuse certain facets of Scripture as God’s communication.

Greek is a medium for divine communication. But like any other human medium, it is imperfect by nature. To borrow the phrase from Paul, Greek (and Hebrew and Aramaic, for that matter) is a clay pot in which the treasures of God are held. Our doctrine of Scripture should be based more on faith in God’s ability to use the limitations of human authors and human languages for his communicative purposes rather than on fear that his communication will somehow fail if we don’t shore up the Scriptures with beliefs about Greek that border on viewing it as magic.

Greek (and Hebrew and Aramaic, for that matter) is a clay pot in which the treasures of God are held.

Greek writers and tall tales

Let me finish with an anecdote from my own journey as a Greek learner. After my first semester of Greek study, I had a conversation with another former seminary student about the Advanced Greek Grammar course at my school, the course in which they read only extra-biblical Greek. I said something to the effect of, “I think it would be difficult to read non-biblical Greek because for me Greek is a language of revelation.”

I have long since crossed that bridge: I now read more non-biblical Greek than biblical Greek each year. But this story touches a significant part of the “Greek is super-precise” story. By the time most students get to seminary, they have associated Greek with divine revelation. Most learners never learn the language well enough to engage with Greek outside the New Testament, so they never have to face the obvious fact that ancient Greek writers told tall tales, made fart jokes, and argued that Christianity was a religion of fools—all using the same Greek language in which the New Testament is written. It is true that Greek is an instrument of divine communication. But for that to be true, it also had to be a human means of communication before, during, and afterward. Human languages never escape imprecision and ambiguity. Greek is no exception.

Ancient Greek writers told tall tales, made fart jokes, and argued that Christianity was a religion of fools—all using the same Greek language in which the New Testament is written.