“Now return the man’s wife, for he is a prophet, and he will pray for you and you will live. But if you do not return her, you may be sure that you and all who belong to you will die.” — Genesis 20:7

In the drama of the broader story of Genesis 20, we risk missing something quite significant for biblical theology: Abraham is named a prophet.

When Abraham sojourned in Gerar, he pretended for the second time that Sarah was his sister. Not knowing this deception, Abimelek took Sarah to be his wife. Abimelek proclaimed his innocence when God appeared to him in a dream and threatened his life.

In response, the Lord directed Abimelek to have Abraham intercede for him “for he is a prophet” (Gen 20:7). Jeffrey Niehaus, in his three-volume Biblical Theology series, notes the significance of this reference.

* * *

God tells Abimelek something about Abraham in Genesis 20, and what he says has a Christological aspect.

Abraham the prophet

It is important to remember that Jesus was a prophet. The word “prophet” occurs for the first time when God says to Abimelek, “Now return the man’s wife, for he is a prophet, and he will pray for you and you will live. But if you do not return her, you may be sure that you and all who belong to you will die” (Gen. 20:7). Afterward, “Abraham prayed to God, and God healed Abimelek, his wife, and his female slaves so they could have children again, for the LORD had kept all the women in Abimelek’s household from conceiving because of Abraham’s wife Sarah” (Gen. 20:17–18).

Clearly, Abraham’s prayer makes possible the further life of Abimelek and his folk (v. 7a), and apparently, one form their deliverance takes is God’s healing them so they can reproduce (v. 18). Maladies can have physical or spiritual causes; they can be brought about naturally, or by demons or, as here, by God. We know the Lord can heal any malady, even death. Unquestionably he can heal a malady he himself has imposed, and that is what we find in this passage.

Abraham the type

The Christology of such a case is apparent from several factors.

First, Abraham is a prophet and therefore a type of Christ who was the prophet par excellence.

Second, God gives a warning about sin, both verbally and in the form of a physical affliction. At God’s initiative the prophet can heal the affliction in connection with repentance on the part of the one warned. In Abraham’s case his own deceptive act was the occasion of God’s warning affliction to the king, and in this Abraham is not like Christ. But this weakness or flaw in him highlights an aspect of Christology already noted: it is his office that makes an Old Testament individual Christological, and not his character. Abraham is a type of Christ by virtue of being a prophet, not because he is perfect in virtue. The Lord justified Abraham because of his faith, not because of any moral perfection or attractiveness he may or may not have possessed.

Third, although one is first told explicitly in Genesis 20 that Abraham is a prophet, the fact that he is a prophet has already been made apparent from two things: (1) he has heard from the Lord and has been given direction/instruction (i.e., torah) by the Lord (even before the Lord cut a covenant with him); and more important (2) he has mediated a covenant from the Lord to his household, a household that will expand to become the Israel of a later covenant and beyond that to become the household of faith, the Israel of God under the new covenant. His being a covenant mediator prophet places him in a small but distinguished company of such prophets, through whom the Lord worked pivotally as history unfolded: Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, David, and the last and greatest of them all, Jesus.

***

This excerpt is adapted from chapter 3 of Biblical Theology, Volume 2: The Special Grace Covenants (Old Testament) (Lexham Press, 2017).

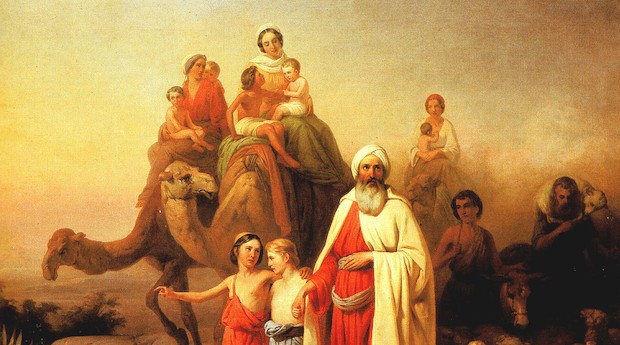

Header image: Abraham’s Journey from Ur to Canaan by József Molnár (1850) on display at Hungarian National Gallery. commons.wikipedia.org