This is not an obituary for Francis I. Andersen, Hebrew scholar and coauthor of the Andersen-Forbes syntax database of the Hebrew Bible, who passed away last month. If you’re unfamiliar with his life and achievements, the Christianity Today obit or his Wikipedia page has you covered. Better yet, read this tribute by his longtime collaborator, A. Dean Forbes.

Truth is, I didn’t know him for very long, but he left an impression on me. I have deep admiration and affection for Dr. Francis I. Andersen. I also have a few stories.

(Side note: if you’re not familiar with Hebrew syntax, you might find this post helpful.)

***

First of all, he preferred to be called “Frank” unless his name was on the cover of an article or book, and he asked me that if I ever needed to use a picture of him to use this one because his wife thought it captured his smile particularly well. I can’t disagree:

I hate to use the word “jovial” because I don’t think it quite captures the mix of warmth, kindness, intellect, and focus that characterized Frank Andersen as I knew him. Opinionated. Wise. Playful, but not frivolous. Demanding, but welcoming. I think I’m going to stick with jovial.

When I think about Frank, I’m reminded of a passage in Ecclesiastes:

Go, eat your food in pleasure and drink your wine with a merry heart, for God has already favored what you have done. Always let your garments be white, and let not oil be lacking upon your head. Enjoy life with your beloved spouse all the days of your vain life which has been given to you under the sun, for that is your portion in life and in your toil which you are toiling under the sun. Everything which your hand finds to do, do it with your strength, for there is no action, or accounting, or knowledge, or wisdom in Sheol, whither you are going. (Ecclesiastes 9:7–10, Anchor Yale Bible)

He worked hard and enjoyed life. It’s no more complicated than that.

***

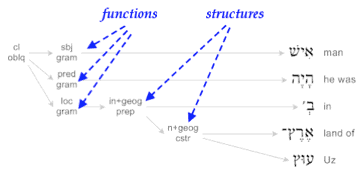

My connection to Frank was through our edition of the Andersen-Forbes syntax database, mentioned in that CT obit:

Today the Andersen-Forbes database is used by Logos Bible Software, with a syntax search engine and phrase-marker graphs that open up the grammatical structures of ancient Hebrew. It is one of the research tools available in the “Clergy Starter” package, as well as other Logos software. —Christianity Today

In October of 2004, I was the Logos employee that developed the Logos product about which they’re talking. I’m still not a Hebrew language specialist, but I had inherited responsibility for maintaining our various Hebrew texts. I had a typographer’s viewpoint: I knew the Hebrew alphabet—all the jots and tittles—and a fair bit about our Hebrew products as digital resources. I used to say I knew a lot about Hebrew without actually knowing any.

So it’s fair to say that this project presented me with a growth opportunity—which is a fancy way to say I was out of my depth.

But before I go too much further, I should say that it’s impossible to talk about the Andersen-Forbes syntactic analysis without talking about both Francis I. Andersen and A. Dean Forbes. Their collaboration spanned decades, and they wrote many papers together. Frank was a Hebrew grammarian and commentator. Dean is a polymath, a Hewlett-Packard alum, an inventor, and a genius in his own field of cardiac electrophysiology. Dean was the chief technical officer of their two-man operation, and without him, there wouldn’t be an Andersen-Forbes syntax database. (There might have been an Andersen stack of papers instead.)

This is because Frank, for all his knowledge and skill, had an antagonistic relationship with computer software. By the time I knew him, his eyesight was poor, and reading off of a screen was difficult for him. For a while, I would get emails from Frank in 36-point font because that’s what he was comfortable reading. “See with what large letters I am writing!” he would tease, echoing the apostle Paul in Galatians.

That being the case, most of my interactions on the Andersen-Forbes project were with A. Dean Forbes. Early on, it was mostly Dean helping me to understand the unique data formats they had developed over the years, while I was writing programs to convert their files into a format that could be digested by Logos Bible Software.

If you think that sounds tedious, you are correct. Scholarship and making software are both endurance sports.

Thus, for many months, I only knew Frank Andersen at a distance. An impression grew in my mind of a pedantic, dusty old professor with an oddly roundabout way of expressing himself who would send long documents of detailed and pointed critique on my work. Dean was the good cop, who patiently walked me through their various file formats, some going back to the days of mainframes. Frank was the bad cop with high standards and expectations to match.

Dean was in California, and Faithlife is in Washington, so I met him in person several times. Frank, on the other hand, lived in far-flung Melbourne, Australia, and was an octogenarian whose traveling days were mostly behind him.

That’s all to say he was more myth than man to me for much of the early stages of the project.

***

I said Dean was an inventor. He and Frank had to invent nearly every tool and process they used to complete their database. One story Dean told me was how they split the Hebrew text into clauses back in the late 1970s. There was no such thing as a Hebrew computer font back then; you had to use characters that came on mainframe terminal keyboards. So one of the things Dean did early on was to program a dot-matrix font so that they could view a copy of the Leningrad codex that was encoded in IBM characters as Hebrew. The text was already broken into words, but they needed to identify clause boundaries. So Dean rigged up a workstation to use his font that would stream the Hebrew text one line at a time across a monitor. A switch could be toggled any time the end of a clause had been reached, and a mark would go into the output file.

In between the screen and the button was a complex apparatus named Frank, who sat hour after hour—probably hunched over—watching a monitor flashing Hebrew characters and flipping a switch to chop it up into clauses.

That was old-school.

***

Frank and Dean taught me a new word, sitzfleisch. It’s a German word that literally means “sit-flesh,” that is, the fleshy part of the anatomy that you sit on. It’s also the name of a German concept for getting more work done: just keep going, bit by bit until you’re done. It’s not rocket science—unless, of course, it is. I’m sure Dean was the first one to say it to me, but they both used it frequently. Sitzfleisch was the most important ingredient in successful scholarship, they’d say. The secret to finishing is to keep going.

Three decades on, and they were still going.

That word has entered the Faithlife corporate lexicon, and we use it to describe the kind of dogged determination it takes to make software. Sometimes the only thing that stands between you and your goal is many hours of sitzfleisch.

I use the Andersen-Forbes database occasionally usually to answer a technical search question for customers—and I imagine Frank sitting in a dimly-lit corner of some library (Dean tells me it was actually a “freezing computer room”), hunched over a bespoke contraption of lights and wires that Dean had invented just for him, using his sitzfleisch to make it possible for me to hit a few keys and come up with answers that would otherwise be impossible.

I think about that when I’m slogging through my own work, sometimes at the point of despair: My sitzfleisch is an investment that will pay off for others, just as Frank’s was an investment that pays off for me.

***

Much of my correspondence with Frank, mediated by Dean, was complaining. He complained to me that the software the Logos team and I were building wasn’t (ahem) living up to its potential. And I complained to him in the form of log files—reports of bits of data that my conversion programs encountered that were undocumented or were typos or other random glitches. Dean took care of most of my log file reports, but some of them had to be minded by Frank.

We were all responsive to each other’s complaints. Iron sharpens iron, and correct a wise man, and he will love you, of course! Yet, at the same time, I got the vague impression that these correspondences wore on Frank. I was making more work for him, and he was always conscious of the fact that his life might end before his life’s work did. But it couldn’t be helped, really. We were lifting up all the rocks—many of which hadn’t been turned over in decades—and every time something crawled out, it was a tiny setback.

I’m sure that if anything, I was the pedantic one! Or rather, my compiler was.

At the same time, I’m sure some part of him enjoyed chasing the bugs. Dean writes in his tribute:

In addressing any problem, Frank was dissatisfied until he had mastered all its associated data and had accounted for corner cases (“pathological cases,” that is, ones that did not fit gracefully into any paradigm). In the book manuscript that he was working on near the time of his death, he wrote (italics added):

“I have carried out my research in the belief that every difference in language use makes a difference, that every detail, however seemingly slight, might well be significant. I accept the reproach that I have a pedantic obsession with minutiae.”

What I, Dean, brought to the table was my abiding conviction that any difference might instead bespeak inadvertent or intentional alteration of the text (“noise”).

—Dean Forbes, “Francis Ian Andersen, Singular Scholar”

Whether he enjoyed my nitpicking or not, I’ll never know. Still, if you’ve read Frank Andersen’s Habakkuk commentary (and you should), you know that complaints are a natural sort of thing and often quite necessary. It’s how things get better sometimes.

***

One of the challenges in converting the Andersen-Forbes database was that it was optimized for Frank and Dean to build and use in a cycle of iterations. They had published multiple papers using the data they had collected over the years, and publication of the database itself was always in view, but it was still a work in progress at the time. Dean had meticulously documented the technical encoding of various graph structures and grammatical categories—some standard, some novel to their theory of Hebrew discourse—but beyond the academic papers, there wasn’t much written for outsiders.

Plus, publishing in the medium of Logos Bible Software added its own constraints on the formatting, as well as implying a broad audience that included a mix of scholars and laypersons.

It was decided that part of the initial release of the software would include a short glossary to give people a gentle introduction into their terminology. Toward that end, I got on a plane for Melbourne, Australia, in the fall of 2005.

Frank and his wife, Lois, played host in their cozy home near the university. I flew in from Washington state, and Dean and his wife Ellen flew in from California. The trip lasted around a week. I stayed in a little hotel a few miles from the Andersen homestead, and Dean and Ellen picked me up each morning to start our writing sessions. Dean drove, and every time we went through a roundabout, he would remind himself out loud, “Death comes from the right”—they drive on the left side down under, you see. Along the way, he gave me a crash course in linguistics.

Frank Andersen had been built up in my mind by this time, and I was intimidated to meet him. I felt presumptuous, naked without any kind of a higher degree. I had dropped out of a music education program at a state college to go and work for Faithlife (then Logos) as an entry-level ebook production worker. I had been working in my job for about 10 years by that point, but I was in no way qualified for what I was doing—which is still pretty much the case. (Don’t tell my boss, thanks.)

To prepare, I memorized the first few verses of Genesis in Hebrew so I could recite them back with tolerable pronunciation. It wasn’t that I wanted to pass myself off as knowledgeable but that there would be at least one example text we could all talk about without me being completely lost.

In short, I had a bad case of impostor syndrome—except that I actually was an impostor.

I needn’t have worried.

Far from being the curmudgeon I had imagined, Frank was warm and welcoming. It was more like going to visit my grandparents than being hauled before an inquisition, as I had feared. When he discovered I wasn’t educated in Hebrew but music instead, Frank praised me for my interest in such an important subject and told me stories of his family members who also shared that interest. He thanked me profusely for all the sitzfleisch I had put in so far to understand his “idiosyncratic markup.” If anything, he was apologetic for all the “sins” that my programs had uncovered.

He caught me admiring one of the paintings hanging in the living room and asked me what I liked about it, and I told him. “Lois painted that, you know,” he said, beaming.

I had expected to be impressed with his knowledge. But what really impressed me was his warmth. I’ve heard people say he was a natural-born teacher, and I believe it. He was certainly eager to have me as a pupil, if only for a few days. He taught me about his time in Eastern Europe during the Cold War as an exchange scholar; gave me career advice (good stuff, too); tips on biblical interpretation; and even a bit of Hebrew grammar.

That last bit didn’t stick, I’m afraid.

He boasted quite a bit, but always in other people. He was especially proud of his children and his wife and talked them up at every opportunity. While I was there, Frank recommended a good many books to me, but never his own. I think he told me about books Lois had written about a half-dozen times.

***

My main job while in Melbourne was to sit in Frank’s office and take dictation. I had pulled a list of terminology from their database, and they were defining them each in turn. There was a lot of discussion between them, and a lot of rabbit trails. The debates were, as Dean puts it, “typically intense and wide-ranging but never aggressive.”

One conversation I remember vividly (though I’m sure I’ll get some of the details wrong) went something like this:

Me: “Next thing I have on the list is adjectives.”

Frank: “As a morphological category?” Then to Dean: “Do we believe in a Hebrew adjective?”

Dean: “Certainly an adjectival function. It’s in the vectors.” (That’s what they called the combination of morphological and word-level syntax properties that were attached to each word.) “We’ve gone back and forth.”

Frank: “I don’t think I’ve given it any serious thought in fifteen years at least!” Pause. “We think whatever Muraoka thinks.” To me. “Are you familiar with Joüon-Muraoka?” Then he told a personal anecdote that escapes me now. Then finally, “You should read it sometime. A very fine grammar. Very insightful.”

Me: . . .

Frank, to me: “It’s in the hallway, last bookshelf on the left, third shelf, bright blue cover.”

I remember, at one point, I typed “such as” into a list of examples, and Frank read it back and said cheerfully, “‘Such as’—yes, good on you! I just detest it when people write ‘like’ instead of ‘such as,’ don’t you?”

***

We had dinner there in the evenings. Frank and Lois and Dean and Ellen were, of course, old friends, and I was . . . well, I was there. We weren’t allowed to “talk shop” at the dinner table, which was just fine because this group had some great stories they loved to tell. I’ll keep those for myself if you don’t mind.

Around the second or third evening, Frank asked if I’d ever had kangaroo. I said I hadn’t. So later in the week, we had a big pot of kangaroo chili. It was pretty good. They served it over noodles, which offended my Texan sensibilities a bit, but I kept that to myself.

***

After the Melbourne trip, and a lot of conversation with Frank and Dean about their work, their philosophy, and their goals, I wrote a short debrief to circulate inside the company:

When I went to Melbourne to visit Dr. Andersen, one of the things I wanted to discover—other than what kangaroo chili tastes like—was the underlying linguistic/textual/grammatical/etc., philosophy of the Andersen-Forbes databases. Sure, they’ve marked the entire Hebrew Bible for syntax, but what exactly does that mean?

What I found out is that Frank and Dean are hard to pigeon-hole. Dr. Andersen claimed that they are committed iteratists, by which they mean that they proceed one iteration at a time, constantly improving their data, constantly allowing their approach and their data to evolve. Furthermore, Frank and Dean are empiricists, at least to the extent that they will insist that every proposition and assertion about the Hebrew language of the Bible be rigorously tested with observable and quantifiable data to see if it is indeed true. In short: data, data, data. On the other hand, they have not presumed that a particular theory or model of Hebrew is correct beforehand; Frank calls their approach eclectic because they have drawn from the insights and approaches of various schools of thought along the way, and will continue to do so.

That is not to say that their work recognizes no system, only that it is a system unto itself: descriptive rather than prescriptive and complex rather than reductionist. For this reason, the A-F database recognizes more categories rather than fewer.

(That debrief eventually became a longer blog post, which you can read here.)

***

After a while, the project was over. We shipped the syntax database, and it was well-received. That year at the annual Society for Biblical Literature conference, Logos rented out a hotel meeting room and invited as many Hebrew and Aramaic scholars as they could find to attend a little show-and-tell preview. Dr. Michael S. Heiser, then a scholar-in-residence at Logos, was the emcee. He was going to give a talk, and I was going to demonstrate alongside on a projection screen.

At least, that’s how I understood it.

There was some miscommunication on the plan because what actually happened is that Dr. Mike said a few brief words and then handed the show over to me. I was mortified. It was one of those dreams where you come into class only to find that it’s the final, you haven’t studied, this isn’t even your class, and you don’t have any pants on. The inquisition I had feared in Melbourne had finally arrived. Bruce Waltke, of Waltke-O’Connor Hebrew grammar fame, sat front and center.

I survived. I fell back on what I had learned in Melbourne and hopefully didn’t distort too many things. I demonstrated the software and the various bits of data and then opened it up for Q&A, where various people tried to stump me. I fell on my sword a few times, begging ignorance. “I’m just a software guy,” I’m sure I said.

After a while, someone asked Waltke what his opinion was. He had been sitting quietly with hands folded on his lap. “I think,” he began and then paused, “this is going to expose all of our sins.” There was general laughter. What he meant, I think, was just what Frank and Dean always wanted: Their work would be used to check assertions made about the language of the Hebrew Scriptures empirically. In other words: data, data, data.

We did some live querying and came out with a passing grade. Fortunately, the work spoke for itself.

***

Eventually, I moved over to another unit and didn’t work on Hebrew databases anymore. (I’m a fancy-schmancy designer now.) Now and again, I would get called in for a consultation with others who had taken over the maintenance of our version of the Andersen-Forbes database.

I would still get emails from Frank occasionally—mostly of the sort that your grandpa sends you when he can’t get the Wi-Fi to work. To be fair to Frank, he was often running beta versions of the Logos software and his installation always seemed to be in some state of disrepair that wasn’t really his fault.

I get a lot of questions from inside and outside the company. I’ve been here a long time, and I’ve built a lot of things (and sometimes they break). There’s usually a sort of clinical professionalism to these conversations: Hello, here’s my problem. Thanks! Hello, here’s your solution. Thanks!

But.

Frank put great effort into me as a human being. I tried to help him with computer issues sometimes, yes. But he also comforted me when my mother was diagnosed with cancer, and when my parents divorced, and later when my wife left me. He let me know when Lois died and sent the eulogy he wrote for her. He let me know when he got married again. We exchanged family newsletters.

It was rare that I would talk to him—when he got a new computer or when he dropped me a line for Christmas—but each time was profound and touching. I still have emails he sent me, and I read them sometimes.

(Okay, I’m tearing up now.)

There was really no need for him to do that. I was just some kid from some company he worked with once, and it would have been just fine if he’d forgotten who I was as soon as I left his project. That’s what most people would have done, and I wouldn’t have blamed him.

But Frank Andersen wasn’t most people. He wasn’t just a Hebrew scholar—he was a genuinely good person, and I’m glad to have known him, even just a little bit.