I love the Jesus Storybook Bible, because it thrills me to think that my kids might grasp the central storyline of Scripture long before the age at which I did. And the colors and textures are cool. And I like a little whimsy in text and illustration.

As the leader of an outreach ministry which targeted kids in historically underperforming public schools in the deep South, I chose the Jesus Storybook Bible as the curriculum for the primary kids class. The kids seemed to like it. And so did the teachers.

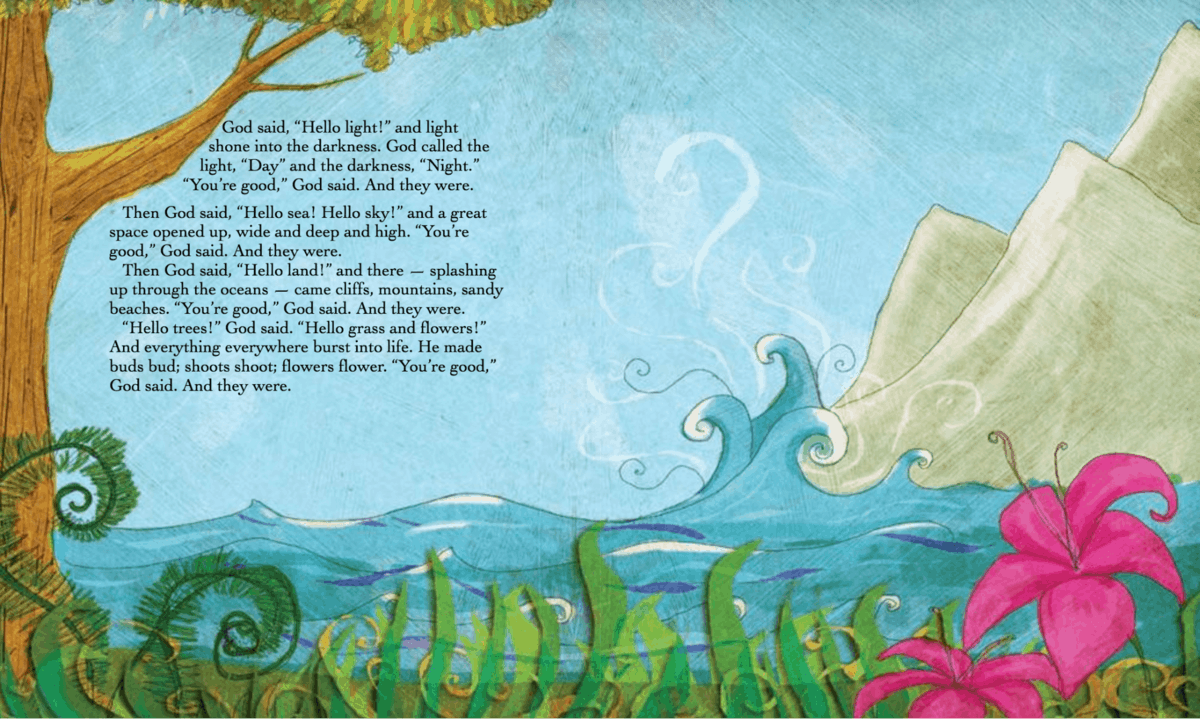

But one day one of those teachers came to me with a concern. He felt that one piece of what I would’ve called vivid whimsy was a little irreverent—and precisely that it dumbed down the Bible. In particular, brilliant children’s book author Sally Lloyd-Jones (no relation to the Dr.) rendered God’s “Let there be light!” as “Hello light!”

I felt a little defensive. I liked Ms. Lloyd-Jones and her work. I intuitively believed (and still believe) that it’s appropriate to bring Bible stories down to the child’s level—and to leave things out that get in the way of understanding. I admire people who understand something so well that they can explain it to kids. Sure, it would be great if kids could read and understand Genesis 1:3 with adult-level depth. But don’t let the best be the enemy of the good: teach kids what they can comprehend. I rose to justify “Hello light!”

But I couldn’t deny the wisdom of this teacher’s words (and I have his permission to relate this story):

I think that sometimes confusion can be caused when we don’t look far enough down the road into the person’s education. Someday they need to understand what the Bible really said. We can also teach students things—as innocent as they may seem—that the Bible is not trying to communicate. Is it asking too much of a child to understand ‘Let there be light’?”

We’re not just teaching kids; we’re teaching future adults.

But… If we teach them things they can’t possibly understand, are we really “suffering the little children” to come to Jesus?

Should we dumb down the Bible?

Yes: because understanding is more important than eloquence

Last week I said no—with special regard to one specific example, changing “chaff” to “dust” in a song I wrote for those very same Bible club kids. But at the end of that post I promised a yes answer in this post. And this question about “Hello light!” helps clarify why I was apparently double-minded on this question.

First: it depends on what you mean by “dumbing down.” Are you “dumbing down” the Bible or “dumbing down” the English? Those are two very different things. In my work teaching and evangelizing, I have consistently made my English less complex in the service of communicating the truth. You “dumb down” your Bible teaching when it is clear that your audience’s understanding and your eloquence have become competing values. Augustine knew this 1600 years ago:

This aim of being intelligible should be strenuously pursued . . . . What use is a golden key, if it cannot unlock what we want to be unlocked, and what is wrong with a wooden one, if it can, since our sole aim is to open closed doors?

Our concern in teaching Genesis 1:3 should be to teach as much of the truth of Genesis 1:3 as we can, even if we can’t hold on to the somewhat grandiloquent “Let there be light.”

In this case, every single major English translation, from the NASB to the NLT, has felt that the wording was intelligible and worth retaining. But we need to be open—and not just open but alert—to the possibility that this language may in fact be unintelligible to people. English speakers as a whole almost never use the “let there be” construction unless they are alluding to the Bible (though, admittedly, the creation of the universe is sort of a one-time thing). If the golden phrase “let there be light” doesn’t open the door of understanding, then we should deign to use a wooden one.

And “Hello light!” is, if not wooden, a good bit more familiar to normal English speech patterns than “Let there be light!” The mere fact that a gifted paraphraser such as Sally Lloyd-Jones felt that it needed a refresh (as did Eugene Peterson) could be an indication that it may have outlived its usefulness. If “Hello light!” is what it takes to get Genesis 1:3 across to kids, I’m fine with it.

Every Bible club kid in the American South knows John 3:16. That’s good. Every Bible club kid in the American South has memorized the phrase “only begotten son.” That’s not so good. These kids have memorized three syllables (be-GOT-in) which are meaningless to them. It’s a time-honored phrase; it’s one they’ll hear elsewhere; it’s in the vocabulary of biblically literate people; there are good reasons to hold on to a common standard Bible translation; and I attach a beauty and a nostalgia to the KJV language in this verse. But something just has to be wrong when the most well-known Bible verse in the country is 8% unintelligible (3 out of 37 syllables in the verse). I have found myself over the years “translating” Biblese on the fly as I read sentences from Scripture to people, and not only in the KJV. Eloquence is good (Acts 18:24), but not when it stands in the way of God’s words (1 Cor 2:1).

Yes: but be very careful of accidentally misconstruing

I will pause here, however, for a warning: translating on the fly can introduce accidental errors. Paraphrasing and “dumbing down” Scripture, even out of the best motives, can mislead your hearers.

“Hello light!,” for example, sounds to me like God is meeting light, not like He’s making it. Lloyd-Jones’s sentence structure in this and the following acts of creation makes it clear (to this adult reader who already knows Genesis 1) that God says hello and then things get created. But that’s a little rhetorically demanding. Will kids get that? In an effort to make the text more approachable, has the author made it less likely that children will grasp the essential element of its message?

And “Hello light!” is charmed with whimsy rather than awestruck with dignity. Is that okay?

When I myself have “dumbed down the Bible” for teaching or songwriting purposes, I have several times come to see later on that I was actually miscommunicating the message of the text.

A personal example: I’m not a top-flight, award-winning parent. My children’s projected future SAT scores are not where they ought to be, nor do they know as many Bible verses and catechism questions as they probably should. So when a fellow Christian parent mentioned that he felt his toddlers ought to know, at least, the Ten Commandments and a few other basic Bible facts, I was ashamed. I thought, “I can do this. I should do this. We’re doing this.” And I sat down to put those commandments in a form understandable by my (then) three-year-old and almost-two-year-old. This is what I came up with:

- There is only one God.

- Don’t worship statues.

- God’s name is important.

- God’s day is important.

- Honor your father and your mother.

- Don’t murder.

- Be faithful in your marriage.

- Don’t steal.

- Don’t lie.

- Don’t want what isn’t yours.

We could quibble about whether “don’t” really captures the gravitas of “you shall not” (and whether “Thou shalt not” has a little too much gravitas). But I wanted these ten commandments to be useful for the nurture and admonition of my toddlers right away; I didn’t want to have to wait till they could grasp the significance of the commands before I could quote the commands to them during toy disputes. There’s an immediacy and power for toddlers in “Don’t want what isn’t yours” that “Don’t covet” just doesn’t carry. “Covet” would be, for them, a Biblese word disconnected from real life.

I felt good about my abridgements. But then I read The Unseen Realm by Faithlife’s own Michael Heiser, and he argued pretty persuasively that the Bible itself recognizes the existence of other (lower-case “g”) “gods.” (He leans in particular on Psalm 82:1, but we won’t get into that now.) I suddenly realized that my formulation of the first commandment, though motivated by love, was potentially misleading; I realized that God’s way of putting it had more depth and design than I was aware of: “Have no other gods before me” implies that there are gods vying for our affection, something I and my children need to know.

I still defend my impulse in abridging the Ten Commandments: I love my children, and I refuse to teach them things they can’t understand when, with a little elbow grease and a few less-immediately-necessary truths saved for later, I can make the Ten Commandments understandable. But I’ve got to be very careful.

Yes: but rely on gifted popularizers

And this is why we need gifted people like Sally Lloyd-Jones. And Kenneth Taylor. And Eugene Peterson. And you, if you’re a Bible teacher gifted by God to serve Christ’s body. This kind of “dumbing down” requires careful thought.

I want to defend the impulse behind Lloyd-Jones’s work, too, even if I run into a textual decision I’m not wholly sure of. Because I think Sally Lloyd-Jones engaged in that thought and is, like me, motivated by love for my children. And I think all Bible teachers who love their neighbors as themselves will constantly feel the pull of the needs and capacities of the audiences in front of them. If you’ve never slapped your forehead, as I have, and realized that you’ve gone too far, you probably aren’t trying hard enough to reach your audience.

And I think there are ways to simplify your Bible teaching which don’t misconstrue the text in front of you. For now, I’m sticking with “Be faithful in your marriage” as a faithful summary of “Do not commit adultery” for my young kids. And I got this idea from a gifted popularizer. Yes, I’m “dumbing it down” a bit. “Adultery” is a concept that I think would be difficult for them to grasp. I’m not sure I’m up to explaining it to them, at least. (I’ll leave that to their peers and popular culture.) (Just kidding.) What’s important is that they know Mommy and Daddy love each other and are going to stick together no matter what—and that this is God’s design. When I teach the seventh commandment to my children I am purposefully leaving out some of the truth God put there for mankind, but I think I’m communicating what’s essential, given their needs and capacities. And I’m looking to people like Sally Lloyd-Jones for help.

Yes: because you can’t communicate everything a text says anyway

There’s a final, clinching reason I’d like to defend Ms. Lloyd-Jones: Bible teachers are always leaving out truth, whenever they teach. We can’t say everything any given biblical text communicates, whether because it’s too much for the time we have, too much for the congregation we have, or too much for ourselves to handle! The question becomes: given my own gifting and knowledge and prep time (etc.) and the age and maturity (etc.) of the people I’m teaching, what is it from this passage that I need to make sure to communicate?

If you use Logos Bible Software to help you prepare sermons or Bible lessons, you will almost certainly end up knowing things about a passage that you choose not to communicate—simply because through your reading and study you’ll know a lot of things. Some of those things will be obscure grammatical points: please, for example, don’t tell your hearers that “let there be” is a “jussive” unless you’re in a Hebrew class! And don’t tell the second graders in Sunday School that the basic Hebrew radicals in the word translated “let there be” are the same radicals in God’s covenant name, Yahweh—even if you do choose to make that conceptual/textual link clear to an adult Sunday School while discussing aseity within theology proper (“The God who calls himself ‘I AM’ is the very foundation of being; he makes things ‘be.’ ”).

In one very definite sense, you should “dumb down the Bible” when you teach it. You should not tell people everything a given text communicates. You can’t. And in fact you very likely don’t know everything a given text communicates! Take “God is love.” You got that? Like, all of it? How about, “I am the vine, you are the branches…. Apart from me, you can do nothing”? How about “Tell them I AM sent you”? You may have an accurate understanding of those biblical statements, and I hope you do, but do you have a complete understanding? No: you’re fallen and finite. There’s always more you could learn about God’s holy word. You’re not expected to teach the Bible exhaustively, just accurately and lovingly.

Conclusion

Bible teachers, and pastors in particular, should be self-conscious about the truths they’re communicating from a given Bible text and those they’re leaving out. Every time. As long as you’re not miscommunicating the text, it’s part of your calling to be an expert (or at least to be good at getting help from experts) at putting cookies on lower shelves. They’re super healthy cookies, so the people eating them will grow. They’ll be able to reach higher soon enough, and then they’ll turn around and lift up others.

Next week, in a final installment, I want to offer a framework which can help you know when to “dumb down” your Bible teaching or not with self-conscious intentionality, for the good of your hearers and the glory of God.

Mark L. Ward, Jr. received his PhD from Bob Jones University in 2012; he now serves the church as a Logos Pro. He is the author of multiple high school Bible textbooks, including Biblical Worldview: Creation, Fall, Redemption.

***

Free Bible study training

Learn more principles for Bible study with our free 30-day Bible study training course. We’ll walk you through the steps of inductive Bible study: observation, interpretation, and application. Sign up below or learn more about the free training.