We often hear that the church isn’t a building; it’s people. And that’s true. Church isn’t where you meet. It’s who meets. However, this statement can become clichéd, repeated so often that we miss the profound meaning behind it.

In this article we’ll dig a little deeper into what it means that the church is people—what Scripture tells us about what the church is.

The Scripture speaks of the Christian church with many pictures. The church is called …

- Christ’s body (Col 1:18)

- Christ’s bride (Eph 5:25–28; Rev 21:2)

- God’s temple of living stones (1 Cor 3:16; Eph 2:19–21; 1 Pet 2:5)

- A holy city (Heb 12:22-23; Rev 21:2)

But we will focus on the essential meaning of the word “church” in Scripture and what it teaches us.

- Where does the word “church” come from?

- The “church” in the Old Testament

- The “church” in the New Testament

- What is the visible and invisible church?

- One holy catholic and apostolic church

- Where do you fit in?

Where does the word “church” come from?

We might first ask where the English word “church” comes from. The mostly likely source is the Greek word kyriakon, referring to a “house of the Lord”; that is, a place of Christian worship.1

The word can also bear the more general sense of simply indicating something “belonging to the Lord,” especially “the Lord’s day” in 1 Cor 11:20 and Rev 1:10.

How ever the word “church” comes down to us, we usually understand it today as translating a Greek word that is probably closest to our word “assembly.” In the New Testament and in the Greek translations of the Old Testament, this “assembly” is the gathered people of God.2

The first time the word appears in the New Testament is in Matthew 16:18, when Jesus names Peter the “rock” upon which Jesus will build his “assembly”—or, in nearly all English translations, his “church.”3

In the New Testament world, the Greek word for “assembly” could actually be used to refer to any gathering, from a political body (Acts 19:39) to a mob (Acts 19:32). The word also frequently appears in Greek translations of the Hebrew Old Testament (often called the “Septuagint”). While recognizing that New Testament authors may have intended some Greco-Roman overtones, we should first consider how their language reflects the usage of the Scriptures.

The “church” in the Old Testament

In the Septuagint, the “assembly” most often refers to the assembly of Israel. Deuteronomy 4:10 and Deut 18:16 speak of the assembly as a specific event, the “day of assembly” when Israel first gathered together at Sinai to hear God. So, the nation of Israel became Yahweh’s “assembly” by encountering the one who had delivered them from the bondage of Egypt, and by hearing his word. This assembly of Israel included men, women, children, and even sojourners—some non-Israelites living amongst the people (Deut 31:12).

A worshipping assembly

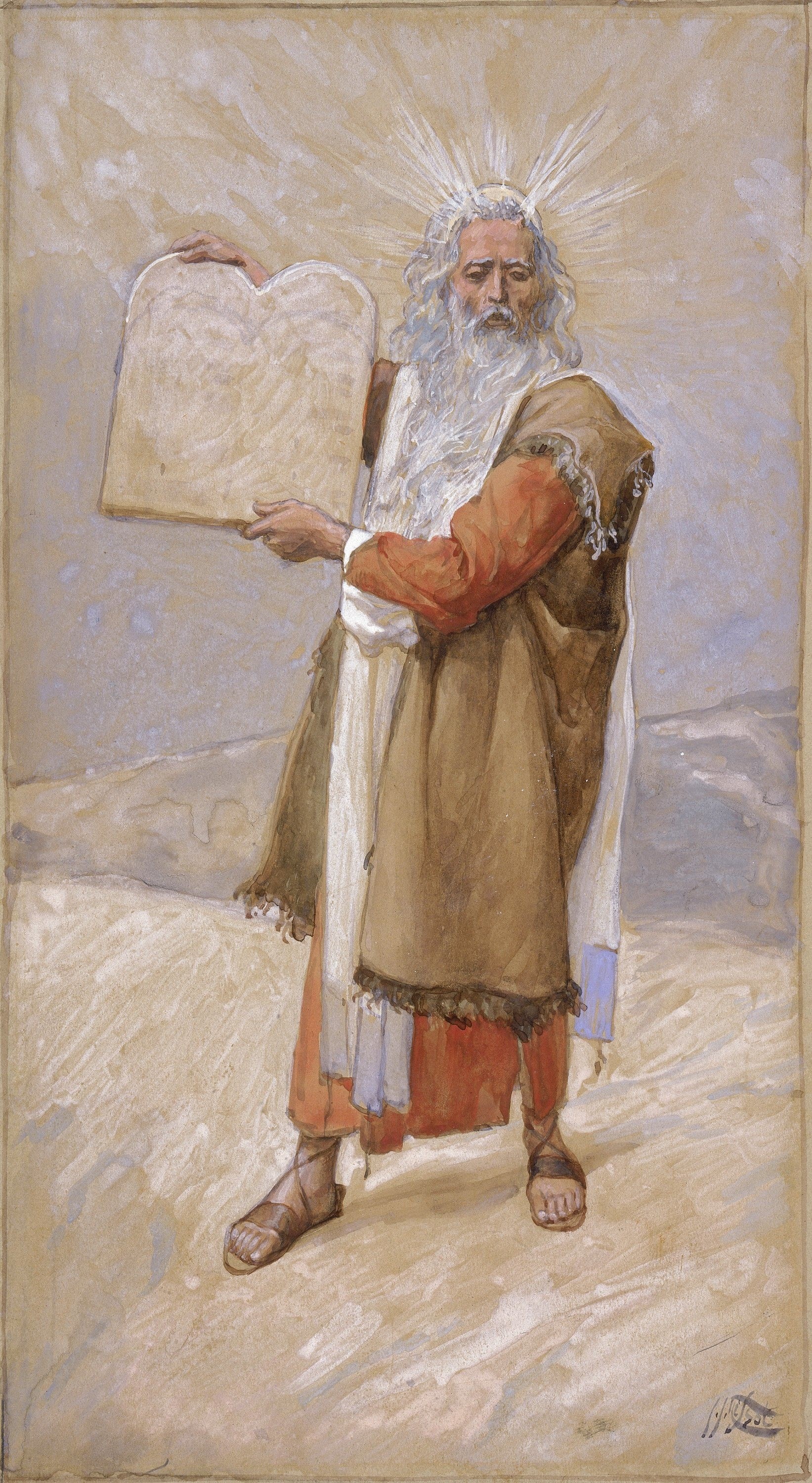

In contrast to the Greco-Roman assemblies we see in the book of Acts, the assembly of Israel was a worshiping body. In the renewal of covenant in Deuteronomy, Moses reminded the people of Israel of their first assembly at Sinai (Deut 4:10) before exhorting them to avoid idolatry (Deut 4:15–19) and to keep the original Ten Commandments. These commandments begin by reminding Israel of Yahweh’s deliverance of them from Egypt and the subsequent command to worship him alone (Deut 5:6–7). To punctuate the restatement of the Ten Commandments, God gives the great commandment to love Yahweh with all our heart, soul, and might (Deut 6:4). He desires not only obedience from his assembly, but faith and love.

Israel was to be not only a kingdom, but a priestly kingdom and a holy nation. Its “assembly” was not merely political—but it was not merely religious. It was both political and religious (Exod 19:6).4 Because of this, full admission into the assembly of Israel was by male circumcision—not merely a civic rite, but a religious one. Passover, the primary memorial feast of Israel, was restricted to circumcised Israelites and their families. If a sojourner wished to keep Passover, he needed to become fully Israelite—to fully join the priestly kingdom by circumcision (Exod 12:43–48).

Gentiles and Israel’s assembly

The rules for inclusion in the assembly of Israel may seem very exclusive. But remember that we saw that the Gentile sojourners were invited to hear the words of Yahweh and to worship him. The sojourners in the land are actually named as part of the assembly. While they were excluded from the Passover, no other feast of Israel explicitly excludes them, and the sojourner is explicitly included in the celebration of the Feast of Weeks, 50 days after Passover (Pentecost), and the Feast of Booths (Deut 16:9–11; 13–14)

The worship of Yahweh is not only for the special kingly priests of Israel but for the nations as well. This looks forward to a time when God will draw all nations to himself (Eph 2:11–13).

The “church” in the New Testament

God’s gathering of nations into one great assembly began at the great Pentecost of Acts 2. After Jesus ascended into heaven, the Holy Spirit filled the fledgling Christian church, and the first miracle he produced sent a definite message: the Spirit gave the earliest Christians the ability to speak the tongues of many nations. This was a signal that the Gospel of Jesus Christ was to go forth into the whole world. Gentiles would no longer be in any way second class in God’s assembly.

In the church, both Jew and Gentile would become equal partners—one people, a new royal priesthood in Jesus Christ, our priest-king (1 Pet 2:9). In this assembly there is neither Jew nor Greek, neither circumcised nor uncircumcised. All are one in Christ (Gal 3:28; Col 3:11).

Like the assembly of Israel, the Christian church is founded upon an encounter with the living God. The same God who delivered Israel from Egypt has now become flesh in the person of Jesus Christ and saved us from slavery to sin and death (Col 1:13–14).

Just as Yahweh, after redeeming his people from Pharaoh, commissioned and constituted Israel as an assembly at Mount Sinai, Jesus, after redeeming his people by his cross and resurrection, constituted his church on a mountain, sending them into the world to make disciples of all nations by baptizing them and teaching them to obey his word (Matt 28:16–20).

The New Testament church is the community constituted by baptism into the Name of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. This assembly, this church, is full of disciples dedicated to observing the commandments of our Lord Jesus Christ. All people redeemed by Jesus and filled with the Holy Spirit are members of Christ’s church.

What is the visible and invisible Church?

To this point we have been talking about the church in mostly visible terms, as the community of God we can see in a particular place and time. This church has visible members that we can greet and care for, and a biblical organization of earthly leadership (Acts 20:17; Eph 4:11–13; Tit 1:5; Heb 13:17).

Christian theology often recognizes, however, both the visible and invisible aspects of the church. The Westminster Larger Catechism asks:

Q. 62. What is the visible church?

A. The visible church is a group made up of everyone—from all ages and all places—who professes the true religion, and of their children.6

The church “visible” is all people now alive, existing in time and space, who confess the apostolic Christian faith.7 It is the church you would see if you were somehow able to see every Christian living on earth today.

Q. 64. What is the invisible church?

A. The invisible church is the whole number of the elect who have been, are, or shall be gathered into one under Christ the head.8

The church has an “invisible” aspect because we cannot see the saints of past centuries today (although we inherit their witness), nor can we see those who will come after us in the future (although they will inherit our witness). The catechism also teaches that the group of those who are in the invisible church does not included apostates or unbelievers, but only those who have true faith in Christ, who will persevere to the end.9

Although we cannot see them, we should always be aware of the church not only on earth, but also in heaven where faithful believers have gone before us. When we worship, even though we may see only the few people around us, we are spiritually united with all the saints (Heb 12:22–24). In our Christian worship we already participate in the “age to come” (Heb 6:5).

One holy catholic and apostolic church

This church “invisible” is also called the “universal church,” or the “catholic church.”10

Most importantly, the invisible and visible church are not two different churches. They are, rather two aspects of the church as it is evident in history. Members of the invisible church are, or have once been, visible by virtue of their baptism and confession.11

The church is the body of Jesus Christ, and he is its head (Col 1:18). The apostle Paul emphatically insists that Christ is not divided (1 Cor 1:13). Since baptism into one Name and faith constitutes this church of Jesus Christ, we shouldn’t think ultimately of different churches, even though we gather in different places under the label of many Christian denominations. It isn’t wrong to speak of Christian churches, of course. Scripture does this (Acts 15:41; Rom 16:5; 2 Cor 8:18; Rev 1:4), since each local church gathering is a distinct “assembly.” However, we must always remember that the church of God, redeemed by Christ, is one body, with many members (Matt 16:18; Eph 5:25-32; 1 Cor 12:12; John 17:22).

There is one body and one Spirit—just as you were called to the one hope that belongs to your call—one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of all, who is over all and through all and in all. (Eph 4:4–6)

The great visible witness of this fact is the Lord’s table. Whenever the church partakes of the Lord’s Supper, it confesses and exhibits unity in Christ. And in that moment, the Holy Spirit binds us together to make our confession true through our partaking (1 Cor 10:16–17).

Where do you fit in?

If you are baptized into the holy Triune Name, then you are a member of Jesus Christ’s great “assembly.” You are called by his name (Acts 15:17; Jas 2:7) and have a place in his church. And you do not have only a partial place, as did the sojourner in Israel’s assembly. You have a full place, no matter if you are man, woman, or child; no matter your nation, your age, your background.

God first calls you to assemble with your fellow members to worship him in regular fellowship (Heb 10:23–25; 12:28), to devote yourself to hearing the Word and praying with the saints, to break bread (Acts 2:42), declaring Christ’s death until he comes (1 Cor 11:23–26).

What happens in the church flows out into the world. Jesus gave his church a mission from a mountaintop, a mission of world transformation. We are called to obey Christ’s commandments and make disciples who will do likewise. Through this humble and faithful work God transforms the world. Jesus promises to be with us “to the end of the age,” and he is faithful to his promise.

The church is the eschatological community—it anticipates the future completion when all political bodies will give way to Christ’s lordship (Rev 11:15), when even earthly family bonds will give way to God’s great family (Lk 20:34). And yet, we not only look forward to these heavenly realities but partake in them even now. For those in Christ, our first and primary community is the church, because it is the eternal community (Gal 6:10; Matt 10:34–38).

Related articles

- 6 Misconceptions Christians Have About the Church

- The Corinthians: Who Were They & What Was Paul Saying to Them?

- When Going to Church Is Hard: 5 Tips

- Karl Ludwig Schmidt, “Καλέω, Κλῆσις, Κλητός, Ἀντικαλέω, Ἐγκαλέω, Ἔνκλημα, Εἰσκαλέω, Μετακαλέω, Προκαλέω, Συγκαλέω, Ἐπικαλέω, Προσκαλέω, Ἐκκλησία,” TDOT (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1964–) 531n92.

- The word is ekklesia; from the Greek kaleō, meaning “to call or summon.” BDAG s.v. ἐκκλησία.

- In other words, it is upon the foundation of the apostolic witness of Peter and his fellow disciples that Jesus says “I will build my church.”

- This may suggest avenues for considering how the Christian church should relate to the civil realm.

- We find in the very instructions for Feast of Booths a tantalizing hint that the feast is for the nations. Over the course of the seven day feast, 70 bulls are offered; the same number as that of the nations in Genesis 10 (Num 29:12–32).

- Text has been slightly modernized.

- Baptists and Presbyterians differ over the last phrase: “and of their children.”

- Text has been slightly modernized.

- This is why it is sometimes called the “eschatological church”—it is the church that will be manifest on the last day. Geerhardus Vos, The Pauline Eschatology (Princeton, NJ: Geerhardus Vos, 1930), 316.

- Distinct from the Roman Catholic Church.

- Situations like conversions on the deathbed or in places of isolation or intense persecution are notable exceptions.