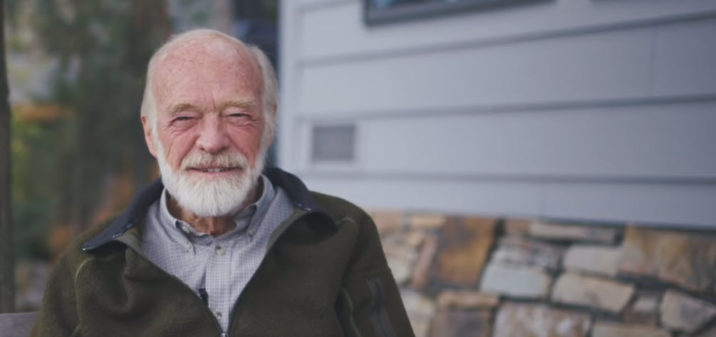

Soulcraft. It’s a word Eugene Peterson thought he’d coined. It was the intended title for the book which became Practice Resurrection: A Conversation on Growing Up in Christ. Little did he know Soulcraft would become the name of a Colorado brewery, but I’m guessing he would have liked that.

Soulcraft was Eugene’s word to describe what we often refer to as discipleship or spirituality. He believed the spiritual is larger than the physical, that there is more to our interior selves than to our physical selves. There is a vast interiority to us which corresponds to the vast world of God. It’s like C.S. Lewis’s wardrobe. It looks like a simple wooden box for the storage of coats, but walk into it and you’ll experience a whole Narnian world.

Poet Gerard Manley Hopkins named this vast and unique interiority within each person “inscape.” Now, we prefer the term “spirituality,” with soul craft being the care and nurture of this God-derived inscape.

As the title of his memoir asserts, Eugene Peterson thought of himself as a pastor. Because of this, pastoral concerns are never far away when writing about soulcraft and so those concerns permeate his five-volume Spiritual Theology. These pastoral/soulcraft concerns are why Eugene veered away from his original intention of becoming a biblical scholar and why he read systematic theologians but didn’t become one himself. But it’s so important to note that Eugene’s pastoral impulse never dulled his academic rigor. (It’s unfortunate I have to write that, but there are far too many inch-deep books written by popular pastors and other best-selling authors.)

This integrated, whole-person, pastoral approach matched what Eugene saw at Regent College, where he taught for 5.5 years. Because of this, he worked well with the Regent approach to Spiritual Theology, which stemmed from founder James Houston’s holistic vision for it. While including the experiential — we’re deal with the soulcraft of real lives here and not just theological concepts — this approach isn’t determined by the experiential. Beneath that are twin disciplines: historical and biblical. Where Houston focused primarily (though not exclusively) on the historical, Eugene focused primarily (though not exclusively) on the biblical.

While the experiential aspect of spirituality is what many popular book writers draw from almost completely, especially those who derive most of their content and insight from personal narrative (and some succeed with great wit and disarming vulnerability), Eugene insisted that Spiritual Theology be grounded not just in the murky, shifting sands of experience. It needs real soil, substantial soil for roots to go deep. And that soil, as noted above, is the rich humus of the Scriptures and the long history of the people of God as they have meditated on and lived out a biblical spirituality.

Though he lacked a PhD, which some foolishly point to as a deficiency in him, Eugene was a rigorous thinker. And that lack of extra letters behind his name wasn’t from a lack of studies. Eugene was on the cusp of completing his doctoral studies when his life took a radical shift away from what he had assumed would be an academic vocation and toward a pastoral vocation. But that shift didn’t take away his proficiency with the biblical languages and theology. Rather, it established that everything he’d write would be somehow pastoral in nature, as we’ve already noted.

Eugene was a tireless and deep reader. As I noted in a previous post, I don’t know anyone who’s read the whole of Karl Barth’s Church Dogmatics once much less twice. For many years, he read Calvin’s Institutes annually, believing they were the key to doing pastoral ministry well. He had numerous volumes from the massive Paulist Press series Classics of Western Spirituality. But unlike so many books on my shelves, his were all read. This is where the historical met the biblical for Eugene. But he didn’t stop there. He also read widely among novelists. I believe his Spiritual Theology arose primarily from the Scriptures, but it included extensive conversation with theology and an immersion in literary narrative.

Eugene pointed me toward numerous writers whose books I devoured but at a much slower pace than he. One of those authors is Anne Tyler. Her many novels center around Baltimore, Maryland, Eugene’s backyard during his years of pastoring at Christ Our King Presbyterian Church. After I had struggled through Tyler’s novel Morgan’s Passing, I called Eugene. “I don’t get it, Eugene,” I said. “I don’t like the book. Morgan isn’t a good guy. He’s so selfish! Why do you like this book?” His response changed me. “Because Morgan is a member of my parish,” he replied. “Not literally. But my parish is filled with people like Morgan. I read Tyler’s books because she helps me be a pastor by helping me understand my congregation.” And with that one phone call, the way I read books was altered forever. I began seeing people as whole stories through pastoral lenses. My sense of soulcraft was broadened significantly.

But Morgan’s selfishness highlighted another sticking point for Eugene. He was ambivalent about the term spirituality. It had come to mean something gooey and formless, an inward sense of self that slipped easily into self-centeredness and often had little to do with Jesus. Even though we are always dealing with the personal (with the lower-case spirituality of our own spirits), we’re also dealing with the divine, with the holy (with the upper-case Spirituality of God’s own Spirit). Because of this, predestination was essential to Eugene for any authentic Spirituality. True Spirituality is formed by the work of God’s Spirit and not just by our own whims. God hasn’t left us on our own to pick and choose from a smorgasbord of American spiritualities, one which is always adopting cultural trends and adapting to our own tastes and sensibilities.

That academic rigor — biblically, historically, theologically — combined with pastoral concerns that any Spiritual Theology be livable and holistic in its soulcraft are what gave Eugene’s books and teaching such mature insight as he continues to draw us through them into the life and love of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

I’d lift a Soulcraft IPA to that if I could get one in Oregon …

Eugene Peterson’s 5-volume Spiritual Theology Series is currently available digitally only at Logos. Get the series today at a fantastic price and get your soulcraft on.